Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 414234

Seventy years ago, in April 1953, Western Air Lines Flight 636 crashed shortly after 11 p.m. into San Francisco Bay, killing eight of the 10 people onboard. According to the accident report, the ceiling was 800 feet broken with visibility of 10 miles in San Francisco when the DC-6 departed, and 700 feet overcast with the same visibility at Oakland, the destination 11.5 miles away.

Flight 636 was cleared under the “visual trans-bay” departure, a procedure for visual flight rules (VFR) operation between San Francisco and Oakland when conditions at both airports had ceilings less than 1,000 feet and/or visibility under three miles. While the approval circumstances were unique to San Francisco Bay, they should sound familiar to modern pilots because, while slightly altered over the years, the trans-bay operation was what we recognize as Special VFR.

Do a quick search through the regulations and you find that the Special VFR clearance can only be issued by ATC upon request and mandates very specific weather conditions. As currently written in FAR 91.157, in addition to ATC approval, the aircraft must remain clear of clouds and visibility must be at least one statute mile (except for helicopters, which require only a half mile). Night approval further requires the pilot and aircraft to be instrument-rated and qualified.

While it can be relatively common in regions prone to fog or smoke, Special VFR tends to generate a lot of confusion, and when associated with an accident, can result in incorrect assumptions from the nonflying public while stubbornly resisting long-term analysis by investigatory agencies.

During the investigation into the 2020 Island Express Helicopters crash that killed Kobe Bryant and eight others near Calabasas, California, it was reported early on that the Sikorsky S-76B transitioned Burbank airspace via a Special VFR clearance shortly before the accident. The weather in Burbank was 1,100 overcast with 2.5 miles of visibility with haze.

The New York Times described this environment as “less-than-optimal visual conditions,” and there was a great deal of speculation in the press about why the pilot failed to file an instrument flight plan. (He was instrument rated and the aircraft was instrument-equipped, but Island Express was not approved to operate IFR.)

The Special VFR clearance was not regarded as part of the probable cause but its prominence in coverage reflected continued questions about what Special VFR means, who should use it, and when it is a reasonable flight safety option.

These familiar questions highlighted that although Special VFR has been around for nearly 75 years, we are still not sure what its impact has been on flight safety.

71-year-old Special VFR

According to the Western Airlines accident report, San Francisco’s trans-bay clearance was approved in April 1952 for the purposes of “expediting traffic” under certain IFR conditions, alongside similar basic minimum visibility deviations between Ft. Worth and Dallas, Texas; Spartanburg and Greenville, South Carolina; and Winston-Salem and Greensboro, North Carolina.

In San Francisco, there was a sliding scale for ceiling/visibility requirements: 1,000 feet required one-mile visibility, 900 feet required two miles, 800 feet required three miles, 700 feet required four miles and 600 feet required five miles. No flights were permitted below a ceiling of 500 feet.

The minimum deviations appeared during the period when basic VFR minimums were still being hashed out in meetings with user groups and the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). The words “Special VFR” first appear in published regulations in May 1952, but their use there is not as it is today. Published as an amendment to Air Traffic Control Rules under Part 60, “Special VFR operations within a control zone” includes details addressing cloud clearance and varying degrees of visibility along with multiple subsections dictating aircraft separation, aircraft congestion, and touch-and-go operations, among others.

The language of that amendment, in conjunction with the San Francisco-type deviations, suggests that the CAB was still working towards definitive exceptions to basic VFR minimums. Five years later, following extensive discussions and the Air Traffic Rules Conference in June 1957, the agency was prepared to introduce and formally use the terms “basic” and “special” when describing VFR minimums. The rules were published in August 1958 with an approved Special VFR clearance for aircraft in a control zone requiring clear of clouds and visibility of at least one mile.

With the new amendments, the CAB published extensive remarks detailing how the rules had evolved and the research conducted in their development. It was noted that Special VFR was studied as a causal factor in accidents only by analyzing midair collisions.

The CAB discussed that “persuasive arguments” had been advanced but there was no case to be made that increasing VFR minimums would reduce midairs. It noted, “One finding is particularly telling: 98 percent of all midair collisions in the past 10 years have occurred in weather conditions exceeding 3 miles in visibility—the other 2 percent have occurred in visibility conditions of about 3 miles.”

There is no evidence that any analysis was conducted before or since the 1950s of accidents involving VFR into instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) or continued flight into adverse conditions as associated with Special VFR activity. The trans-bay deviation was explored in the crash of Western Airlines Flight 636, but investigators concluded the pilots must have failed to comply with the published procedures, which mandated that if ceilings below 500 feet were encountered, the aircraft must climb to 2,000 feet and hold for an IFR clearance. The CAB was confident the deviation was not the problem, but rather what the pilots chose to do when they encountered conditions they did not expect.

The final probable cause in this crash was the crew’s continued descent into the water in an attempt to stay below a cloud layer that investigators believed must have been encountered at 500 feet.

There was also a contributory factor of “sensory illusion,” which prevented the crew from realizing their true altitude. This cause/factor combination is remarkably similar to that of Island Air Express nearly seventy years later. That pilot was found to have continued VFR into IMC which resulted in spatial disorientation and, ultimately, loss of control. He apparently was confused about the helicopter’s altitude, telling ATC shortly before the crash that he was climbing when the helicopter was actually in descent.

Historic Error

By not studying Special VFR-adjacent accidents, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is continuing the historic error of ignoring a plausible mitigating factor in controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) crashes. Finding accidents to study that include Special VFR in the investigation report is not easy, but a recent search of the NTSB database brought up a few that highlight the potential negative impact of the clearance.

In January 1995, a Bell 206B departed Burbank under a Special VFR on a Part 135 charter flight for Wolfe Air Aviation. The ceiling was 300 broken, with 2.5 miles of visibility in light rain and fog. The pilot reported clear of the zone and then crashed into high-voltage transmission wires on the Hollywood Freeway about seven miles south of the airport; two people were killed and two received serious injuries. Radar data showed the helicopter never climbed more than 300 feet above the ground. The probable cause was continued VFR into IMC.

In October 2000 a Cessna Caravan flying for Empire Airlines under contract to FedEx departed on a scheduled flight from Bellingham, Washington. The pilot obtained a Special VFR clearance in a ceiling of 500 feet with a visibility of two miles. Multiple ground witnesses reported the aircraft as barely visible in the fog (some only heard it and never saw it). The Caravan crashed eight minutes after departure into the trees on nearby Lummi Island, killing the pilot and sole occupant. The probable cause was attempted flight into adverse weather conditions and failure to avoid trees.

In April 2002, a Cessna T182 operating under Part 91 obtained a Special VFR to land in Amarillo, Texas; conditions at that time were 300 feet overcast and visibility of four miles. The pilot briefly acknowledged a communication from approach eight minutes after the clearance, but then there was no further contact. The aircraft impacted a power plant about five miles northwest of the airport killing both people onboard. The probable cause was the failure to avoid the power plant and intentional flight into adverse conditions.

In November 2013 a Hageland Aviation Caravan departed Bethel, Alaska, on a scheduled Part 135 flight for the village of Marshall. It overflew that destination due to weather and continued on to its second destination of St. Mary’s, which does not have a control tower. The pilot received a Special VFR clearance to land there from Anchorage Center, located over 400 miles away. Witnesses at the airport reported the aircraft overflew the runway at less than 400 feet and never activated the airport’s lighting system. It subsequently crashed one mile away at an elevation of 425 feet; four people were killed and six received serious injuries. The reported weather at St Mary’s, when the Special VFR was issued, was three miles of visibility and a ceiling of 300 feet. The probable cause was the pilot’s decision to initiate a VFR approach into night IMC conditions.

A common element in these accident reports is an emphasis on events after the Special VFR clearance while distancing the clearance from its prominent position in the causal chain. This was even the case in the rare example of ATC being cited for improperly issuing a Special VFR.

In 1993 an Aero Commander flying under Part 91 crashed on Christmas Eve after the clearance was given into the airport at Chico, California. Investigators found that just prior to the clearance a special weather advisory had been issued with ceiling indefinite, sky obscured, and visibility zero. There were three causes for this accident, which resulted in one fatality and two serious injuries: the improper issuance of the clearance, the pilot’s continued VFR into IMC, and his failure to maintain control following spatial disorientation. The pilot also was not instrument-rated, as required for night Special VFR approval.

This accident was an isolated example, however, and traditionally, as in nearly all accidents involving any pilot decision-making, crashes that include continued flight in poor weather conditions with or without a Special VFR are determined to be the primary fault of the pilot.

As an unnamed FAA official put it to the New York Times during coverage of the Island Express crash, “A pilot is responsible for determining whether it is safe to fly in current and expected conditions, and a pilot is also responsible for determining flight visibility.”

Pressures To Fly

In both Part 91 and commercial operations, however, Special VFR can exacerbate existing pressures to fly. For commuter and air taxi pilots, it can lead to the suggestion that a pilot “go take a look” and see if VFR flight can proceed once out of the zone.

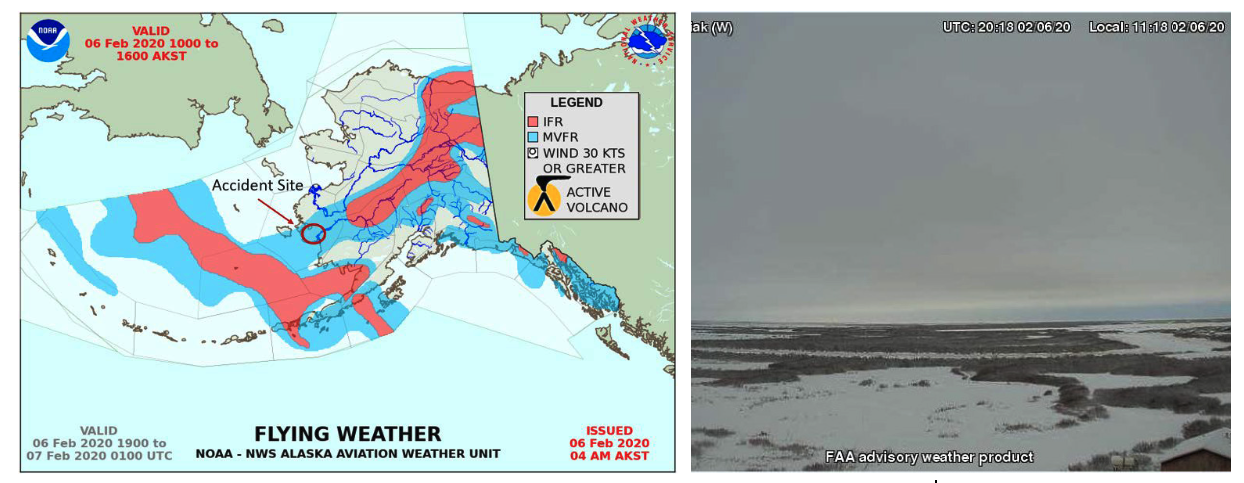

An obvious example of this would be the February 2020 crash in Alaska of Yute Commuter Service’s Piper PA-32 scheduled flight to Kipnuk. As reported by the NTSB, a Special VFR was obtained to depart Bethel Airport with conditions of 600 feet overcast, four miles of visibility, and mist. One minute after departure, visibility was down to a mile and a quarter. When the crash occurred 30 minutes later, conditions at both Bethel and Kipnuk had worsened to one-half mile visibility with the ceiling as low as 400 feet with light snow, mist, and freezing fog.

Investigators never found a definitive source of pressure on the pilot, who was killed with all four of his passengers, but this flight was only his fourth revenue flight for the company and an FAA hotline complaint from the previous summer suggested the regular abuse by management of basic VFR minimum standards. Similar allegations were made to investigators following the accident by former employees.

For Part 91 operations, there is perhaps no more poignant example of the treacherous combination of Special VFR and pressure, primarily self-induced, than the 1996 crash that killed Jessica Dubroff in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Jessica was one month short of her eighth birthday and flying with her father and a flight instructor in pursuit of the fame associated with setting the unofficial child-pilot cross-country speed record. She instigated a media frenzy as they flew their Cessna 177B Cardinal from California in April on a planned loop across the lower 48 to the east coast and back.

Upon arrival at 5:30 p.m. in Cheyenne on April 10, Jessica told reporters she was tired, and according to investigators, her instructor phoned his wife that night and told her he was “very tired.” The group’s overall fatigue was noticed by a member of the media who escorted them to their hotel and later told investigators they discussed being tired but were “adamant” that the flight had to depart the following day by 6:15 a.m. to stay on schedule.

The next morning, after multiple media interviews at the airport, the instructor requested a weather briefing at 8 a.m. He filed a VFR flight plan for Lincoln, Nebraska, and while taxiing out at 8:18 a.m. requested a Special VFR. Visibility in Cheyenne was two and three-quarters miles, with a ceiling of 2,400 broken, 3,100 overcast, thunderstorms, and light rain. The tower approved the clearance and informed the instructor the field was IFR. The aircraft took off three minutes later and crashed almost immediately, impacting the street in a residential neighborhood 4,000 feet north of the departure end of the runway. There were no survivors.

The accident’s probable cause was ascribed to the pilot’s improper decision to depart into deteriorating weather conditions in a slightly overweight aircraft with an unfamiliar density altitude, which resulted in a stall. A factor was a desire to adhere to their “overly ambitious itinerary” due to media commitments.

Special VFR is a valuable tool for operations in areas with specific and isolated weather conditions. However, a failure to thoroughly study its relationship to CFIT accidents and its influence on pilot or operational decision-making hampers any ability to determine if that value outweighs the risk. There are certain airports and regions in particular where Special VFR wields an outsized influence. The FAA either knows or should know about these locations; it would be worth their time to discover just how much they have been missing by ignoring what Special VFR’s permissiveness can persuade a pilot to do.