Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 404866

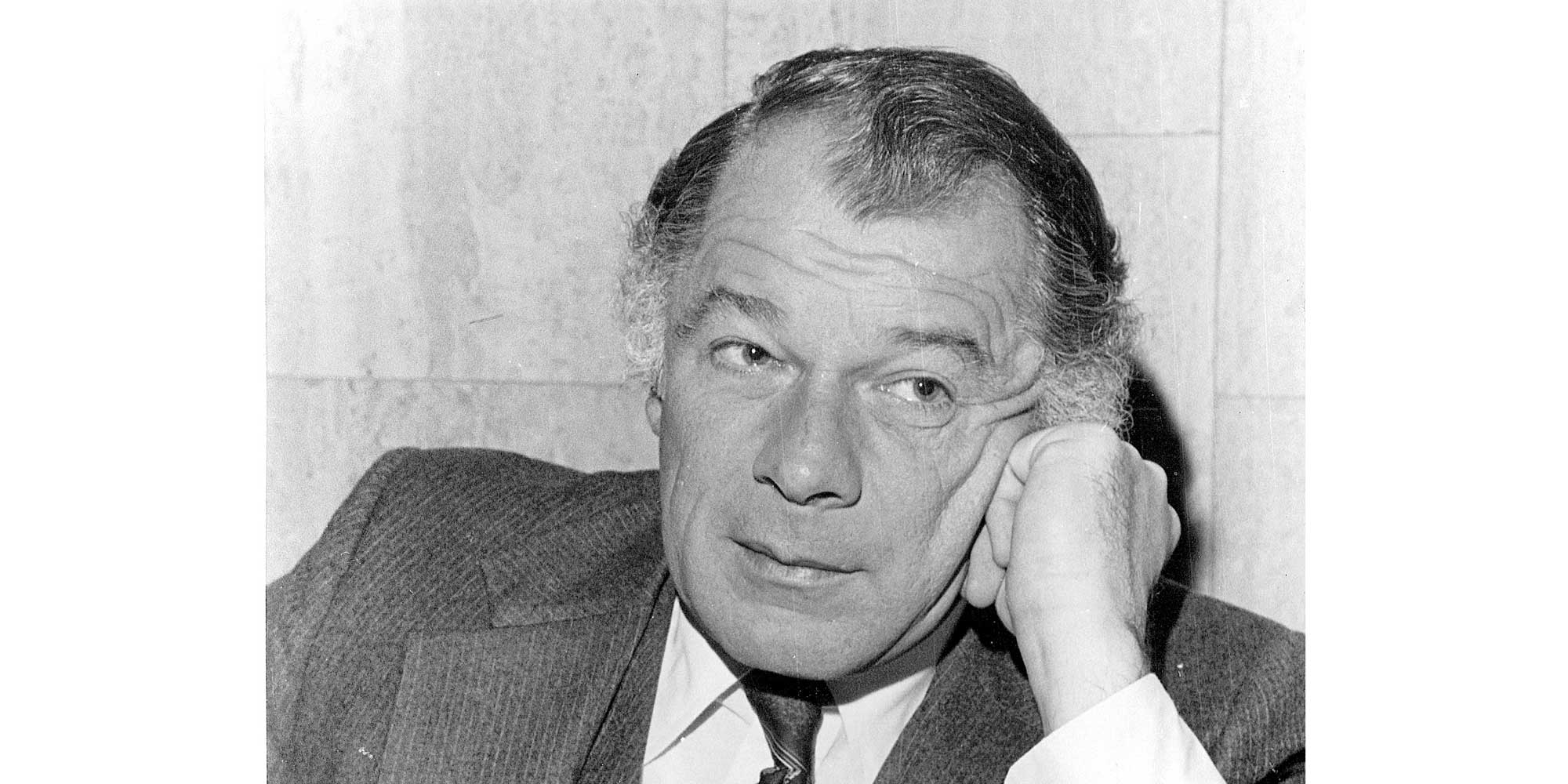

On a brisk 1979 winter day in Menominee, Michigan, David Brandt stepped out of the Enstrom Helicopter hangar and looked skyward. “I was horrified,” recalled Brandt, then Enstrom’s vice president of engineering. A few thousand feet directly above him, F. Lee Bailey, the flamboyant trial attorney, aviator, and owner of Enstrom Helicopter, was about to put the company’s sole example of its new, four-place Model 280L Hawk into a Vne dive. Money from Bailey’s high-profile law practice was keeping Enstrom afloat and the 280L was seen as the key to the company’s future success. If Bailey augered in, it was game over. Brandt had hired an experienced Navy test pilot to wring out the Hawk, but Bailey insisted on personally putting the aircraft through its paces as well. “He was our chief kamikaze pilot,” Brandt said. Bailey pushed the Hawk to its fastest speed yet and recovered the dive. “He was perfect,” Brandt said.

He was also cold. Brandt had neglected to outfit the prototype with a heater, so pilots had to fly it in snowsuits, and the doors were sealed with thick green tape to keep out the cold that felt like -20 deg F.

Initially backed by a group of investors in December 1970, Bailey had taken charge of the dormant Enstrom, which had been all but shuttered by then-owner Purex Corporation for the better part of the year. He would go on to own 95 percent of the company. At first, Bailey had to beat back rumors that he had bought Enstrom to make a fast buck by turning it into a parts and pieces sale. Instead, Bailey revitalized it and by 1977 it was producing 12 helicopters a month.

Under his tenure, the company launched the popular 280 “Shark” three-seat piston helicopter, dramatically increased sales, built a worldwide distributor network, and brought in a talented team including Brandt, an MIT graduate who had worked at Boeing Vertol near Philadelphia. When a corporate recruiter approached Brandt about Enstrom, he was the chief technical engineer for Boeing’s YUH-61, the unsuccessful competitor with Sikorsky for what would become the Black Hawk. “We were flight testing on Long Island” when Bailey’s recruiter first approached Brandt. “I was ready to make a change,” he said.

When Brandt arrived in Menominee he set to work on remediating problems with its sole certified product, the F28, three-seat piston single that included cracked rotor shafts. “There were lots of little problems that needed attention the first couple of years I was there,” said Brandt. Once those were solved, Brandt’s team moved on to working on an improved version of the F28 called the Falcon that was never completed, in favor of moving ahead with the Hawk.

Prior to entering Boston University School of Law in 1957, Bailey had been a Marine Corps carrier pilot. (Bailey graduated first in his class with the school’s highest grade point average in history.) His law practice rocketed to rapid success with a string of high-profile murder cases including Albert DeSalvo (The Boston Strangler) and Dr. Sam Sheppard. By the time he was 34, Bailey’s law practice was national, he had his own weekly network television interview show on the ABC network (“Good Company”), and he was flying his own Learjet.

In his 1977 book, an aviation soliloquy titled, Cleared For The Approach, Bailey explained how he fell in love with helicopters a few years prior to leading the team to acquire Enstrom, building a helicopter hangar at his Marshfield, Massachusetts home, and initially flying a Brantly. In his book, Bailey made the case that helicopters were actually safer than fixed-wing single-engine aircraft in the event of an engine failure because an autorotating helicopter could be landed comparatively faster and in a more confined space. To make the point, Bailey said he routinely demonstrated autorotations to his passengers.

Bailey parlayed his celebrity contacts into Enstrom sales, selling helicopters to A-lister pilots including motorcycle stunt driver Evel Knievel and Las Vegas musical impresario Wayne Newton. Bailey “was a salesman,” recalled Ben Bunting, a courtly Carolinian who was Bailey’s business manager and de facto in charge of Enstrom’s day-to-day operations beginning in 1976.

“He was deeply involved in the marketing,” said Brandt. “He did all that.” This included developing a controversial marketing brochure that featured an attractive woman in a sheer negligee peering out a bedroom window at an F28 about to land on the lawn under the headline, “The Love Machine,” replete with suggestive ad copy that could have been ripped directly from a men’s magazine: “When she’s waiting for you (and you can’t wait to be with her), an Enstrom helicopter will get you together faster. It carries you up and over traffic congestion at speeds in excess of 100 mph and you land within walking distance of her door. And an Enstrom helicopter lets you linger a little longer.” Perhaps, not coincidentally, at the same time he owned Enstrom, Bailey was the co-publisher of a men’s magazine called “Gallery” that had very little to do with fine art. He was also, at the age of 39, into his third marriage.

However, Bailey’s management style when it came to engineering was largely to hire a talented team, point them in the proper direction, and get out of the way, according to Brandt. “He was brilliant, amazing, he had a photographic mind. He could grasp things so quickly.” While Bailey didn’t micromanage, he wanted to be kept apprised of critical Enstrom developments in real-time, even when he was in the courtroom. Accordingly, senior Enstrom executives were outfitted with pagers. When Bailey would get a five- or ten-minute recess in a trial, the pagers would go off and Enstrom managers were expected to call Bailey immediately to give updates and answer questions.

But concurrently, Bailey was “very fair” to Enstrom employees, said Bunting, treating them like family. “He listened and made quick decisions.” To woo Brandt to the company, Bailey personally transported his new engineering chief’s wife, mother, mother-in-law, two Dobermans, and two cats from Philadelphia to Menominee in his Aero Commander. “Imagine piloting a plane for three hours with two Dobermans sitting right behind you,” Brandt laughed as he recalled the flight.

Enstrom had literally bet the company on development of the Hawk, even as the personal helicopter market had all but evaporated in the face of recession. Brandt and his team of 30 engineers had gone from product launch to first flight in just nine months. They had designed the new helicopter to be powered by either a turbine or piston engine—the prototype had a piston—and had worked through the Christmas holidays without a break to make sure the Hawk made its first flight by New Year’s Eve Day, 1978.

Money had been tight at Enstrom for years. Bailey had used the retainer he received for defending media empire heiress Patricia Hearst on bank robbery charges to meet the December 1975 payroll, recalled Brandt. (Bailey had an Enstrom delivered to San Francisco during the trial and would fly it around the city during breaks in the trial, showing it off to a retinue of reporters who always seemed to be in tow.)

When Bunting joined the company he immediately noticed the financial strains even as it churned out record production. “We extended our credit line,” he remembers, but even then sometimes that wasn’t enough and Bunting would be sent out to collect customer deposits so that the company could make payroll. On one occasion he returned to Menominee with 22 deposits.

Enstrom’s tight fiscal condition became ingrained in employee ritual. Every payday turned into a hangar beer party, Bunting said, as they awaited the arrival of Bailey from Boston in his Aero Commander with the payroll on board. “We’d sit around and wait for the plane to come in. It was fun,” Bunting said.

By all accounts, Bailey was a talented pilot, but non-precision, night-time approaches into Menominee’s frequently snow-covered and gusty runways could tax cockpit capabilities of even the most adept aviators. On one such occasion, Bailey plowed his Aero Commander into a snowbank, damaging the nose. An Enstrom crew was dispatched to tow the plane into the hangar and work all night repairing and repainting it “off the books,” according to Mike Stevens, an employee who witnessed the event.

But as Enstrom prepared to campaign the Hawk at the Helicopter Association International’s Heli-Expo in February 1979, company spirits ran high. The helicopter was transported to the show and flew 20 hours of customer demonstration flights there, garnering 62 orders. But it was too late. Enstrom was out of cash and out of credit. “We came home and shut the doors,” Brandt said.

Before the closure, Brandt had formed Enstrom Research and Development Associates (ERDA) to separate the company’s R&D expenses from production costs in an effort to make Enstrom’s bottom line more attractive to lenders and investors. With Enstrom shuttered, he renamed that company, replacing the word Enstrom with “Engineering.” Brandt and Bunting ran ERDA for more than 20 years. The company, moved to an old boat factory in nearby Peshtigo, Wisconsin, was a pioneer in the development of 16 g dynamically-certified aircraft seats for business aircraft and is now part of Collins Aerospace.

Enstrom would eventually be sold to a succession of owners including a group of Saudi businessmen, inventor Dean Kamen, and a Swiss investor. It is now owned by the Chongqing Helicopter Investment Corporation of China and is still based in Menominee.

Bailey would go on to more high-profile cases including the O.J. Simpson murder trial and the protracted and successful fight to reinstate the medical certificate of legendary air show performer Bob Hoover, a struggle that would eventually lead to the “Pilot’s Bill of Rights” legislation. He represented the victims’ families in the Soviet shoot-down of Korean Airlines Flight 007 and the bombing of Pan Am 103 and helped to establish the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization union. He continued to be involved in aviation through several aircraft modification programs for Aero Commanders and Pipers. He had recently relocated to Georgia to be near one of his sons, Scott.

A few weeks before he died on June 3rd, Bailey called Bunting and asked him to send any photos he might have of Bailey at Enstrom with his wife at the time, Lynda Hart. Bunting found a few and sent them along.

“He was always an aviation enthusiast,” said Brandt of Bailey. “He loved that more than the law.”