Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 405206

Much of the momentum for introducing electric aircraft to commercial service is a response to mounting pressure to reduce air transport’s impact on the environment and meet targets for reducing the industry’s carbon footprint. But increasingly, the companies developing the aircraft say a strong economic case exists for moving away from dependence on jet-A fuel that promises significant reductions in operating costs and the potential to make short, thin routes viable with smaller aircraft.

Ampaire has begun the next phase of UK-based flight trials for its plans to convert nine- to 19-seat regional airliners, starting with the Twin Otter and the Islander, to hybrid-electric propulsion. The company’s Electric EEL technology demonstrator is operating between Exeter Airport and Cornwall Airport Newquay in the southwest of England to evaluate operational needs for commercial services that the company says could start by 2024. Senior vice president for global operations Susan Ying told AIN that Ampaire has also started work on a clean-sheet design for a hybrid-electric 19-seater.

The trials, using a converted six-seat Cessna 337 Skymaster, are part of the UK government-backed 2Zero program (Towards Zero Emissions in Regional Aircraft Operations), which is evaluating the case for hybrid-electric flights out of the southwest of England. They follow a series of flights conducted earlier this month in northern Scotland as part of the Sustainable Aviation Test Environment project, which is backed by the UK’s Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund and supported by partners including regional airliner Loganair and Highlands and Islands Airports.

Ampaire is part of the UK-based 2Zero consortium, which was set up to explore regional aviation electric flight solutions. In 2020, it received £2.4 million ($3.3 million) from the government-backed UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) agency’s Future Flight Challenge fund to supplement around £5 million that the partners are investing themselves. The other partners include Exeter Airport, Cornwall Airport Newquay, Loganair, Rolls-Royce Electrical, the University of Nottingham, the Heart of the Southwest Local Enterprise Partnership, and UK Power Network Services.

Rolls-Royce is working on a new battery system that could be swiftly swapped while aircraft are between flights. The aircraft engine maker is also working on a thermal management system for the EPS with a focus on reducing weight.

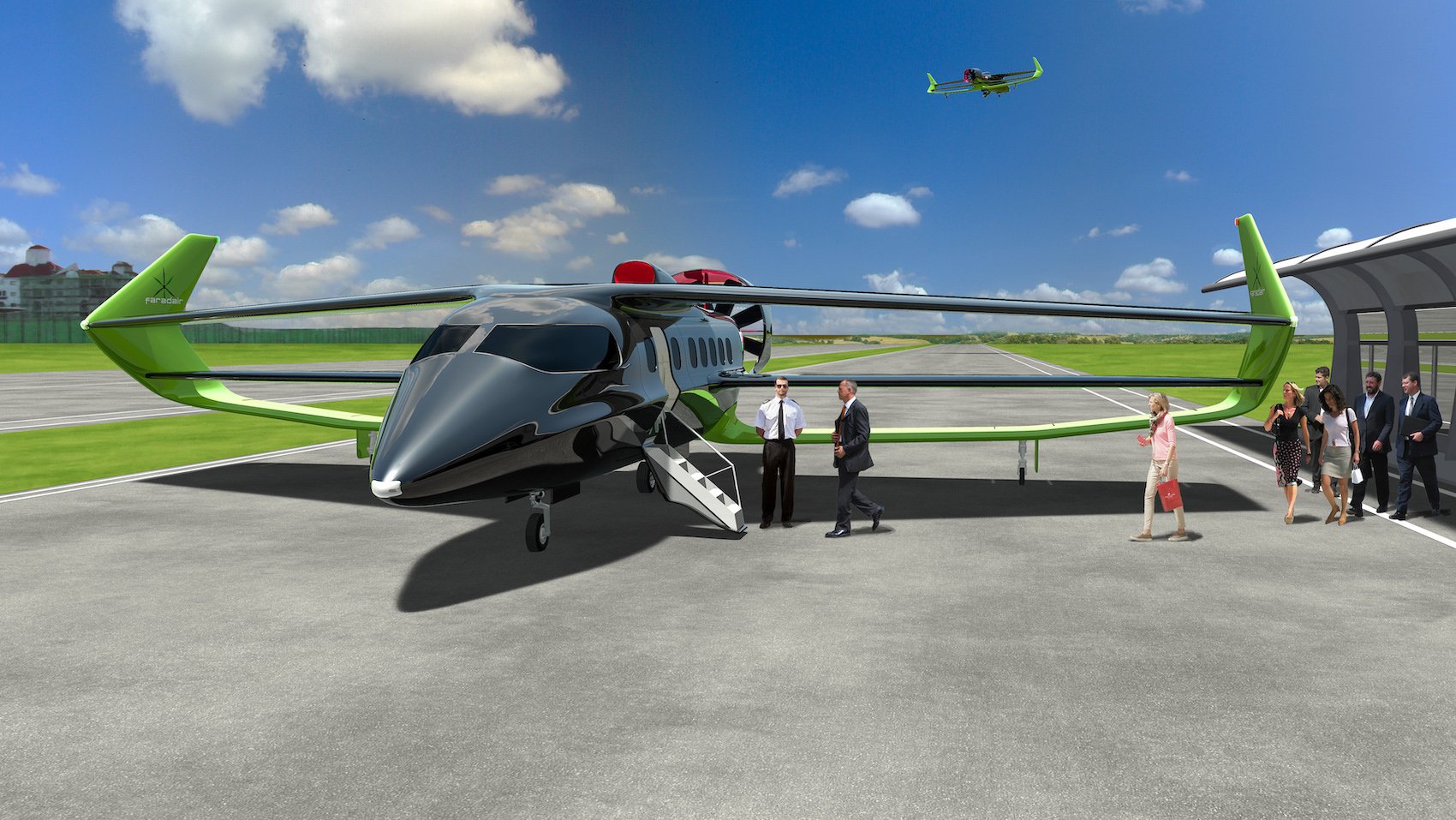

However, this is far from being the only option for airlines looking to turn their fleets green. UK-based start-up Faradair is finalizing the design for its Bio Electric Hybrid Aircraft (BEHA). The hybrid-electric 18-seat model will be powered by a Honeywell turbogenerator and electric motors provided by MagniX, which has its own plans to convert Twin Otters to electric propulsion.

Faradair aims to certify the BEHA under Part 23 rules by 2026 and says the fixed-wing aircraft will be able to fly up to around 1,000 nm from runways as short as 1,000 feet. Its projected service ceiling is 14,000 feet and its cruise speed is around 200 kts.

According to company founder and CEO Neil Cloughley, his aircraft has the potential to bypass busier airports, reducing journey times and opening up trips for which no commercial airline service currently exists or would be viable. He has argued that some regional airlines have struggled to sustain profitability by operating from major airports, such as London Heathrow where elevated cost structures make it hard for them to be competitive.

“Imagine if you could carry up to 18 passengers from an airfield five miles up the road [from a major airport] without the crowds, security [delays], and high-cost base,” he told an aviation industry webinar in May. “That way, you could start something really interesting, and so our short-field performance will be very significant. Our program is about providing mobility as a service and being disruptive.”

In Sweden, Heart Aerospace is developing an all-electric 19-seater called the ES-19 that it says will be ready to enter service by the end of this decade with a range of around 217 nm. In July, United Airlines and its regional affiliate Mesa Air announced a provisional purchase agreement for 200 of the new model, with options for 100 more. The U.S. companies also said they are joining Breakthrough Energy Ventures in a $35 million Series A funding round for the start-up.

Across the border in Norway, Scandinavian regional airline Wideroe is the launch customer for Tecnam’s all-electric P-Volt. Rolls-Royce Electrical is developing a propulsion system for the nine-seat commuter model, which is based on the Italian manufacturer’s existing P2012 Traveller twin-piston utility aircraft.

The P-Volt’s short takeoff and landing capability should make it suitable for the many small airports Wideroe serves across Norway, where a lot of communities are faced with long road connections to other cities. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, Wideroe operated around 400 daily flights to 44 airports, with many of these routes being shorter than 150 nm. The Norwegian government is pressing for the introduction of electrified aircraft on domestic flights starting in 2030 to meet its objective of an 80 percent reduction in emissions by 2040.

Earlier this year, Pipistrel confirmed its plans to develop its Miniliner family of 19-seat regional airliners, which it says will be able to serve sectors of up around 544 nm and at speeds of up to 261 kts. According to the Slovenia-based company’s chief technology officer, Tine Tomazic, the aircraft will have 40 percent lower direct operating costs than similar-sized existing twin-turboprop aircraft and be 25 dB quieter.

Pipistrel is evaluating several possible propulsion options for the Miniliners but appears to favor a hydrogen-based powertrain with a 1MW fuel cell system. It is considering both a hybrid configuration with a turbine and direct burn of hydrogen with a goal of being able to operate four 350-km (190-nm) sectors in succession with a 100-km or 45-minute diversion reserve. The aircraft would likely need almost 2,600 feet of runway.

Meanwhile, two hydrogen propulsion specialists are advancing plans to convert existing regional airliners. And these options are due to come to market well before Airbus achieves its objective of getting a hydrogen-powered airliner into commercial service by 2035 under its Zero E program.

ZeroAvia, which has also received UK government funding, intends to install a pair of 600-kW electric propulsion systems and hydrogen fuel tanks on 19-seat Dornier 228 aircraft provided by UK-based operator Aurigny Air and AMC Aviation of the U.S. The company aims to get a supplemental type certificate for the conversion by 2024.

Universal Hydrogen is focusing on plans to convert types such as the ATRs and Dash 8s using a 2-MW fuel cell powertrain and its own concept for storing liquefied hydrogen in capsules that would be loaded into a compartment at the rear of the cabin. In April the California-based start-up secured $20.5 million in Series A funding and its backers include JetBlue, Airbus, and fuel cell specialist PlugPower. Icelandair, Spain’s Air Nostrum, and Alaska-based Ravn Air have all signed letters of intent to replace their existing Pratt & Whitney turboprops in their Dash 8 and ATR fleets by 2025.

Meanwhile, Ampaire is using the Electric EEL to complete the development of its three-module electric propulsion system (EPS), which consists of an electric motor, a power inverter unit, and a set of batteries. On the converted Skymaster, this system drives a single propeller at the front of the aircraft, while a Continental IO-550 piston engine, mounted on the rear of the aircraft, acts in the original pusher-configuration role.

After completing flights between Scotland’s Orkney Islands and Wick on the mainland, the Electric EEL made a 418-mile flight from Perth to Exeter on August 23. This broke Ampaire’s previous record for the longest hybrid-electric sector of 341 miles, which was flown in October 2020 between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Ying told FutureFlight that once development work on the EPS is complete it will likely take another two years to finish the STC process for aircraft like the TwinOtter and the Islander. Ampaire, which is now owned by flight booking platform Surf Air, believes it can deliver reductions in operating costs of around 30 percent.

In addition to cutting emissions from jet-A-burning engines, the company says, it can deliver 30 percent reductions in operating costs, which would support a business case for new scheduled services between smaller airports. Ying told an August 24 media briefing at Exeter Airport that the existential challenges faced by regional airlines during the Covid crisis have made it even more imperative to drive down operating costs while also making short-haul services environmentally sustainable. “It’s not enough to just demonstrate that the [hybrid-electric] propulsion technology works,” she stated. “You’ve got to be able to show that it’s economically feasible and that the operational aspects are as well.”

Proving the operational feasibility of hybrid-electric fleets is a key aspect of Ampaire’s flight trials in the UK, building on work it did last year in Hawaii with regional operator Mokulele. Working with its airport and airline partners, the company has been focusing on factors such as recharging batteries during fast ground turnarounds, which in small airfields on Scottish islands can be limited to between four and 10 minutes.

At Exeter Airport, Ampaire is pricing out three potential solutions to make recharging electric aircraft efficient and economically viable. These include installing direct charging stations using renewable energy sources to connect directly with the aircraft; a process for charging sets of batteries that would then be used to recharge aircraft batteries; and arrangements for rapidly swapping out batteries while aircraft are on the ground. The company’s engineering team is also working on plans to design a series of batteries specifically for aviation use rather than depending on hardware developed for road vehicles.

Pete Davies, managing director of publicly owned Cornwall Airport Newquay, sees the new aircraft opening up exciting routes for communities that otherwise have to accept long drives or inconvenient rail connections to reach other parts of the UK. “We have an obligation to be part of projects like this because the people of Cornwall [England’s most southwesterly county] are looking forward to flying being a more viable and greener option. This could leapfrog other modes of transport.”

In his view, the transition to electric or hydrogen aircraft could happen sooner in airports like Cornwall, from which scheduled flights include a 16-seater operation on the 60-nm sector to the Isles of Scilly and 29-seater connections to cities in the north of England. Davies says he anticipates UK government support to stimulate operators to step up to meet its objective of zero-carbon domestic flights by 2040.

For 2Zero and Sustainable Aviation Test Environment program partner Loganair, the work with Ampaire is part of the UK operator’s Green Skies initiative through which it has committed to achieving carbon-free aircraft operations by 2040. It has started this process by offsetting carbon emissions from its flights but wants to firm up a plan for converting or replacing its existing fleet, which includes Islanders, Twin Otters, and Saab 340s, as well as ATR 42s and 72s and the Embraer ERJ 135 and 145 jets.

“We’re driven by what technology is available and none of the planned solutions are there yet, but we will transition to these types of technologies,” Andy Smith, Loganair’s head of sustainability strategy, told AIN. This is why the operator is supporting several initiatives, including ZeroAvia’s program and the UK-based Project Fresson, which is looking at switching Islanders to hydrogen.

In its collaboration with Ampaire, it is sharing detailed information on its operational requirements. “We’re one of the few larger [regional] airlines that still operate smaller aircraft, and with the short runways and austere facilities we depend on, assumptions about recharging battery-based electric systems can be very wrong,” said Smith.

Like other operators, Loganair is having to calculate at what point it should commit to an available hybrid, all-electric, or hydrogen-based fleet upgrade option, mindful that improved technology might be just around the corner. It is attracted to hydrogen because this can be produced in a completely carbon-free way, using water and solar power.

“The nub of the problem is that there is so much exciting technology coming and we don’t want to get stuck in a chicken-and-egg situation [between converted aircraft that could be available sooner or new aircraft that might take longer], so there is some possible pain for early adopters,” Smith stated.

In his view, government support or inducements will be needed for airlines, especially in the wake of the Covid disruption, to be able to justify the significant financial commitment for going green. Some that are pushing for zero carbon aviation have suggested that governments should start taxing commercial aviation fuel to force a switch from fossil fuel, but Smith said that wouldn’t help or be reasonable.

“Carbon taxation won’t help the airlines to switch,” he commented. “The cost of sustainable aviation fuel is already three or four times higher than jet fuel. When jet fuel cost as much as that previously, airlines were going out of business left, right, and center. Airlines have made powerful voluntary commitments. We’ve already been paying for carbon through [the European] emissions trading scheme for almost a decade, but our rail competitors haven’t had this cost, even when they are burning diesel.”

In the first instance, Loganair expects to face increased ownership costs from switching to new or converted aircraft, so it is pressing companies like Ampaire to reduce the overall costs of their propulsion solutions. “This could make airlines rethink their operating models,” he concluded. “It could make flying very short distances practical, and this will mean changes such as being able to communicate digitally with customers [over flight availability] and making the airport experience quicker and more seamless.”

A new joint study published in August by transportation consultants Roland Berger and the Royal Netherlands Aerospace Centre (NLR) questions whether electric aircraft can ever compete on cost with existing airliners. The study's answer is that they might be able to at a small scale, but only with some form of government subsidies.

For the purposes of the study, NLR developed a hypothetical 19-seat sub-regional all-electric aircraft based on modifying a 1980s-vintage BAE Jetstream 32 twin turboprop and determined that it would be able to operate on routes of up to around 700 km (381 nm). This was based on what the authors, Nikhil Sachdeva, senior project manager with Roland Berger, and Wim Lammen, a research engineer with NLR, admit is the optimistic assumption that batteries with an energy density of 1,000 Wh/kg would be available. Even then, it is acknowledged that a turbine engine would be needed as a backup.

At face value, the report concludes that this aircraft would be 10 percent less expensive than a conventional sub-regional aircraft due to its lower energy and maintenance costs. However, the authors say this does not take account of real-world factors such as airport charges and the need for more sectors to be flown to carry the same number of fare-paying passengers as larger regional airliners. Once these are factored in, the imaginary electric aircraft would be 35 percent more expensive than Embraer’s larger ERJ-145 jet, 45 percent more expensive than the ATR42 twin-turboprop, and 65 percent more costly than the much larger A319neo.

The authors propose that governments should subsidize airport charges to encourage the use of more environmentally friendly electric aircraft. They also acknowledge that these could use smaller, less-expensive airports that would offer more direct door-to-door connections for travelers.