Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 425788

Note: AIN is using “notam” as a word per the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) definition and not the way the FAA uses notam as a contraction of “Notice to Airmen.” According to ICAO, a notam is “A notice distributed by means of telecommunication containing information concerning the establishment, condition, or change in any aeronautical facility, service, procedure, or hazard, the timely knowledge of which is essential to personnel concerned with flight operations.”

On the night of July 7, 2017, the flight crew of Air Canada Flight 759, flying an Airbus A320, lined up with San Francisco International Airport’s Taxiway C instead of Runway 28R after being cleared to land. Four airliners were waiting on Taxiway C for takeoff, and the A320 kept descending toward them until it reached 100 feet agl and flew over the first airplane, then started a go-around. At its lowest point, the A320 reached 60 feet agl and was an estimated 10 to 20 feet above the second airplane in line (the distance between both airplanes) before climbing away.

There was a notam for the closed parallel runway—28L. It was in the pilots’ flight release package and included in the airport’s ATIS flight information broadcast, which pilots must review prior to arrival. The closed runway notam was on page eight of a 27-page briefing package in a section titled “Runway” and came after 14 clearly less urgent notams. Six of these were for OBST CRANE, none of which intruded into the flight path for Runway 28R. Two were for taxilane closures, three for taxiway closures, and one for taxiway CL LGT U/S, which means “centerline lights unserviceable” in notam-speak.

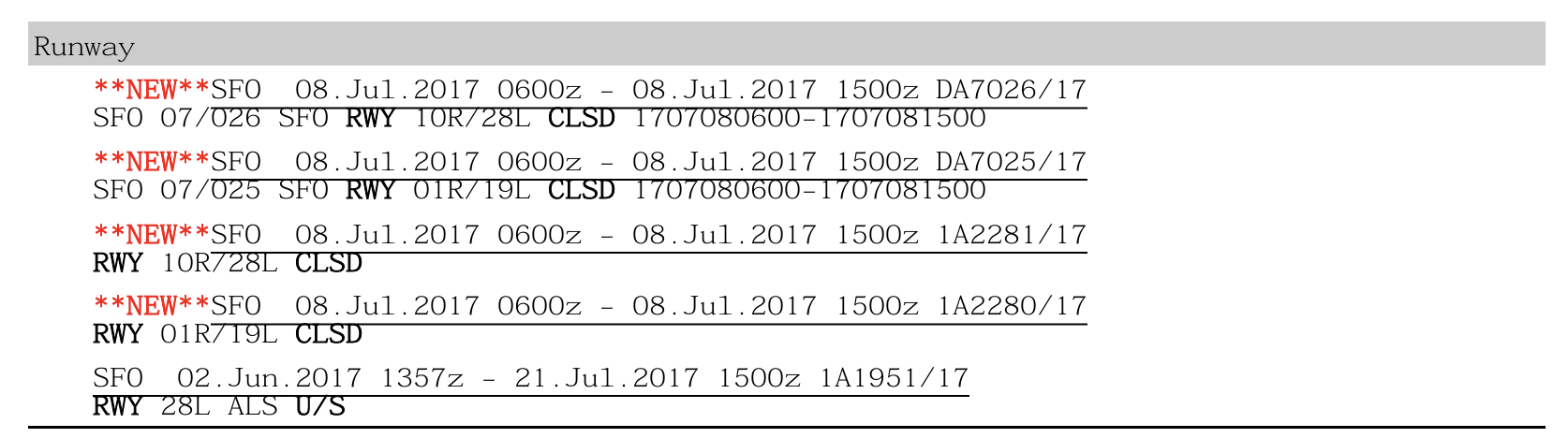

After all of these less urgent notams, the Runway section listed five notams that looked like this:

It should be noted that even though the critical runway closure notams came after a set of virtually useless notams, the importance of the closed runways was highlighted by the word NEW in red. Otherwise, there was no ranking of these critical notams that might have signaled to the pilots that there was something important that needed their attention.

In follow-up interviews about the incident, the first officer stated that he could not recall reviewing the specific notam that addressed the runway closure. “The captain stated that he saw the runway closure information, but his actions (as the pilot flying) in aligning the airplane with Taxiway C instead of Runway 28R demonstrated that he did not recall that information when it was needed,” according to the NTSB report. “Both crewmembers recalled reviewing ATIS information Quebec but could not recall reviewing the specific notam that described the runway closure.”

According to the NTSB, “Features of the notam text emphasized the closure information, such as the use of bold font for the words 'RWY' and 'CLSD' and a '**NEW**' designation in red font with asterisks before the notam text, as shown in figure 10.98. However, this level of emphasis was not effective in prompting the flight crewmembers to review and/or retain this information, especially given the notam’s location (toward the middle of the release), which was not optimal for information recall. A phenomenon known as ‘serial position effect’ describes the tendency to recall the first and last items in a series better than the middle items (Colman 2006).”

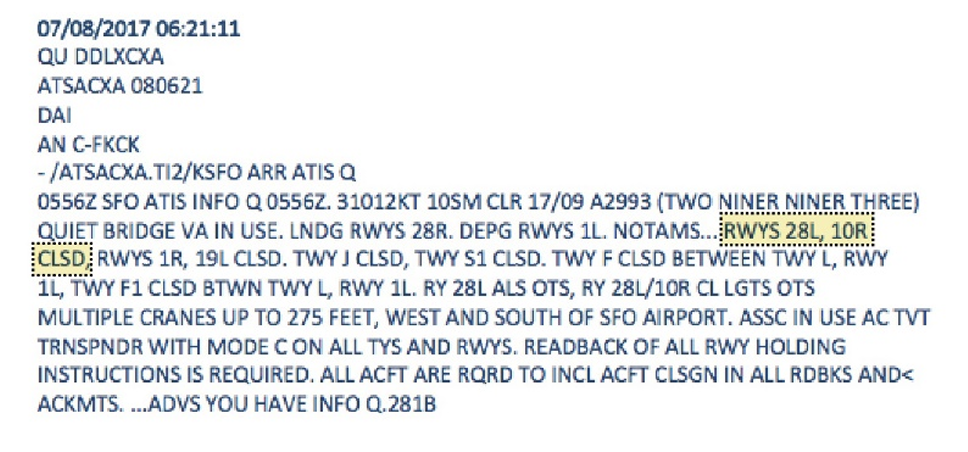

This is what ATIS Quebec looked like as received via the aircraft’s onboard aircraft communications, addressing, and reporting system (ACARS). In other words, the pilots didn’t listen to information Quebec on the KSFO ATIS radio frequency but read it as an ACARS transmission. (The yellow section highlighting the runway closure is from the NTSB report, not the way it looked to the pilots.)

The report continued: “The ACARS message providing ATIS information Quebec, as displayed in the cockpit, was 14 continuous lines with all text capitalized in the same font. As shown in figure 11, the notam indicating the Runway 28L closure appeared at the end of line 8 and the beginning of line 9. The uniform presentation of the ATIS information could have contributed to the flight crew’s oversight of the runway closure information.”

During a hearing on the incident, then-NTSB chairman Robert Sumwalt was prompted by the near-collision to single out what he called the “messed up” notam system.

Sumwalt claimed that the “crew didn’t comprehend the notams” and, as an example of the confusing notams pilots are faced with, read this complex entry from that same Air Canada flight’s briefing package, just one of the many for Toronto Pearson International Airport: “**72**YYZ 06.Jul.2017 1400z - 31.Jul.2017 2200z 1Y1247/17 TWY AK, TWY R BTN TWY B AND TWY AT, TWY B BTN TWY B1 AND TWY R NOT AUTH TO ACFT WITH WINGSPAN GREATER THAN 214 FT.”

“Why is this even on there?” he asked. “That's what notams are: they’re a bunch of garbage that no one pays any attention to,” adding that they’re often written in a language that only computer programmers would understand.

Sumwalt also relayed a recent experience he had flying the jumpseat into North Carolina’s Charlotte Douglas International Airport, saying, “There were pages and pages and pages of notams, including one for birds in the vicinity of the airport…When are there not birds in the vicinity of an airport?”

The NTSB issued six safety recommendations to the FAA after the Air Canada incident, one of which—A-18-024—was to develop a “more effective presentation of flight operations information to optimize pilot review and retention of relevant information.” So far, that recommendation’s status remains “Open—acceptable response.” The definition of that term is: “Response by recipient indicates a planned action that would comply with the safety recommendation when completed.” This means that the FAA has yet to comply with the recommendation, eight years after the near-collision and seven years after the NTSB recommendation.

In fact, notams are not supposed to be used for information that might be considered normal—for example, birds in the vicinity of an airport. Such a notam provides no useful information because birds move around, and there is no way to assess the level of risk involved, other than to maintain the normal watch for potential hazards such as birds.

According to an FAA presentation on notams for airport managers, “A notam is a notice containing information essential to personnel concerned with flight operations but not known far enough in advance to be publicized by other means. Notams concern the establishment, condition, or change of any component (facility, service, procedure, or hazard) in the NAS [National Airspace System]. They must state the abnormal status of a component of the NAS—not the normal status.”

There is plenty of guidance for those who are responsible for creating notams, and the foundational instructions come from the ICAO, which sets standards for member states to implement. ICAO’s guidance still advises the use of contractions and capital letters, which are leftovers from the days of teletype machines when bandwidth was extremely limited.

For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, ICAO and the world’s aviation authorities have continued with this protocol. The FAA, for example, requires that “Contractions and abbreviations designated for ICAO usage as specified in FAA Order JO 7340.2, Contractions, and ICAO Document 8400, ICAO Abbreviations and Codes, must be used in the notam system. When an ICAO−usage contraction is not available, plain text is required, except for the list of differences in Appendix C.”

ICAO’s documentation lists common terms and their coding information and “uniform abbreviated phraseology” to help those who submit notams ensure they use the proper descriptors. However, this isn’t a perfectly clear process, and there is room for confusion.

For example, the contraction “act” can mean two things in ICAO-speak: when used by itself, it means “activated,” but when preceded by the word “volcanic,” it means “activity.” To add inconsistency, the word “deactivated” is not abbreviated to something like “deact” but is spelled out in full. A word like “canceled” is contracted to “cnl,” which is hardly intuitive. Yet “prohibited to” is spelled out instead of contracted to something like “phbto.” And one might wonder, why are runway centerline lights “rcll” when many other mentions of lights use the contraction “lgt” like “twy cl lgt” for taxiway centerline lights (which, to uphold consistency, ought to be “tcll”). Or stopway lights as “stwl” versus “thr lgt” for threshold lights, and not “thrl” as it should be for consistency.

The FAA seems to think that this is a good idea. From the notam presentation: “Notams have a unique language characterized by the use of specialized contractions. Contractions are imperative to the notam structure because they make communication more efficient and allow computer systems to parse important words.” It is not clear how the inconsistent use of contractions makes it easier for computers to parse important words.

Notams are so important—even though many are not considered essential for aviation safety—that the FAA paused domestic airline departures for an hour and a half when the U.S. notam system shut down on Jan. 10, 2023. The problem was due to a contractor who “unintentionally deleted files while working to correct synchronization between the live primary database and a backup database,” according to the FAA, which added, “The FAA made the necessary repairs to the system and has taken steps to make the notam system more resilient.” Yet since then, the FAA had to inject delays into the system on Feb. 1, 2025, due to another outage, this time reportedly a hardware issue, and again on March 22.

Thousands of new notams are generated each day, and tens of thousands are in various databases. Efforts to make the notam system work better frequently mention starting with those who write the notams and claiming that the system’s problems originate with poorly coded notams or ones that simply shouldn’t have been submitted in the first place.

ICAO, in fact, points out on its NOTAMeter website that simply removing old and obsolete notams would instantly reduce the number of notams in the database by 20%. NOTAMeter is a tool to analyze the age of notams submitted by the 193 ICAO member states.

Unfortunately, the NOTAMeter tool is not current. The last date for which data was published is July 1, 2023, and at the time, it said there were 34,733 notams in the world. A list of the 193 member states shows how many old and very old notams exist for each state, with some of the highest numbers from countries in Africa. Yet even the U.S. and France have a significant number of old notams, 13% and 13.3%, respectively.

ICAO has launched a notam improvement project, with the following goals intended to help civil aviation authorities and data originators: using ICAO’s NOTAMeter to analyze a state’s notams, identify old notams and cancel or replace them or simply update aeronautical information products; delete non-compliant notams; come up with procedures to prevent inputting of non-compliant notams; and examine training and competency of notam personnel.

Notably, the above attempts to address the problem from the notam submission angle. Some in the industry thought there might be a better way.

OpsGroup to the Rescue

In February 2023, after the U.S. ground stops due to the notam system failure, OpsGroup convened a team to answer the question, “What do pilots want” from notams. In May, OpsGroup convened a team of 300 people for a “Notam Sprint,” a five-day effort to “Design a prototype system to post-process notams, tag them, summarize them, and then sort/filter into a newly designed briefing package.”

One of the team’s earliest realizations was that it would be impossible to fix the problem from the bottom up just by brute-forcing the correct submission of notams and by trying to get notam submitters to do a better job. The real challenge—and the resulting epiphany—was figuring out how to make more effective use of the existing notam system.

This addresses a fundamental truth about the slow and nonexistent notam improvement efforts by state CAAs: anyone is free to do with notams what they will. CAAs can create their own improved notam systems, building off the existing database. Electronic flight bag app developers can build notam transcription and organization features into their apps, putting the important notams at the top of the list, highlighting them, and turning them into readable plain English, even using uppercase and lowercase letters that are proven to be far easier to read than all caps. ForeFlight, for example, does this with notams that are tied to specific airports.

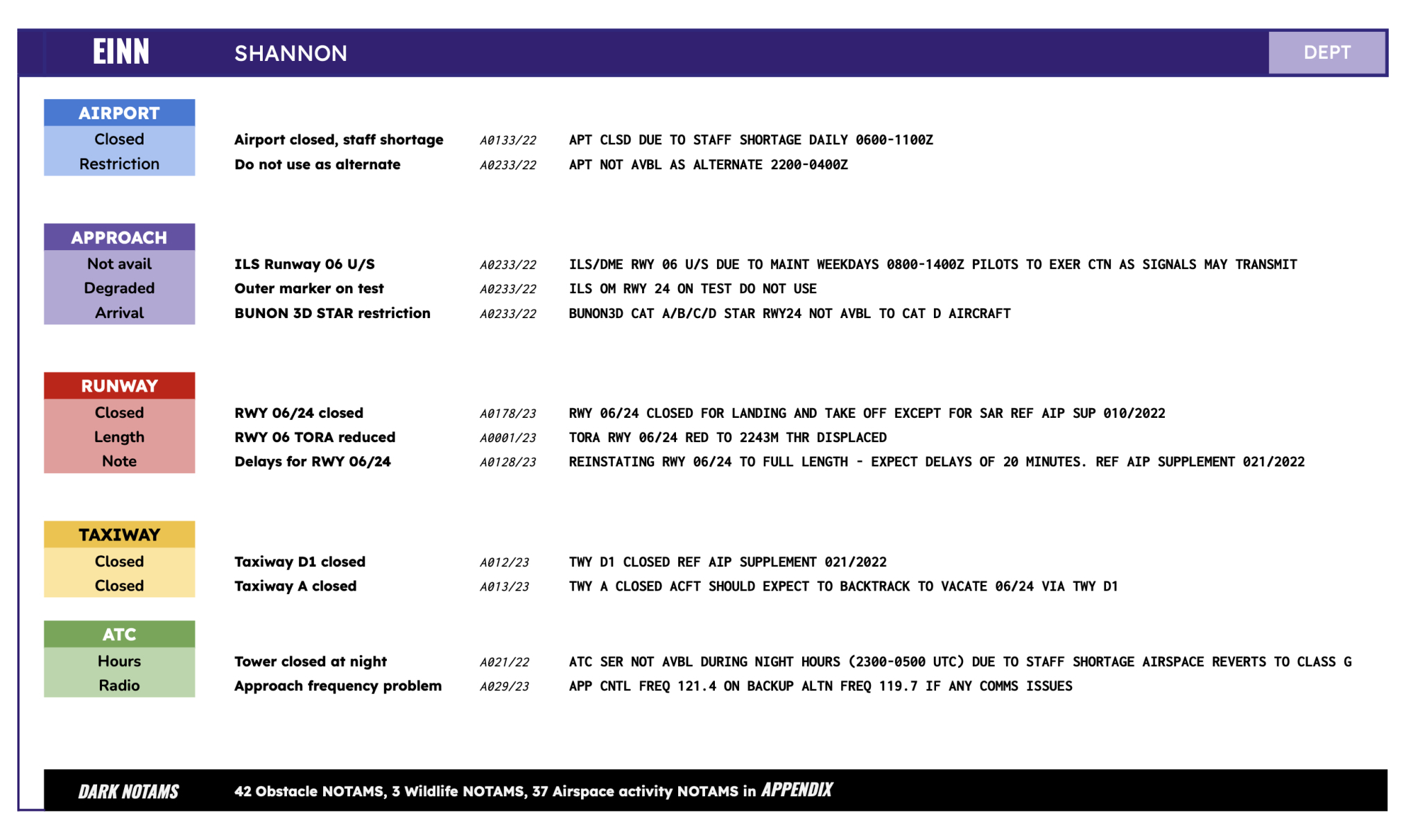

An airline or flight operation can even use software tools that OpsGroup helped develop to run their own notam improvement programs. A key result of the Notam Sprint was the creation of a categorization system that puts important notams at the forefront and delegates nearly useless ones (“dark notams,” as OpsGroups calls them) into an appendix.

“It doesn’t solve it at the back end (the notam office),” OpsGroup explained, “but it doesn’t need to, anymore. Until this year, we were all convinced that the only way to fix notams was to change the way notams are issued by notam officers, perhaps adding a tag to each one so we could organize them better. But AI has launched a cannonball of change into the aeronautical information sphere. Notams are just the start of the change we can expect to see.”

OpsGroup does point out that this solution isn’t in the form of a simple smartphone app or some other end-user software application. For the Notam Sprint testing, the team created an application programming interface that demonstrated the benefits of this approach, and airlines and aircraft operators could build on that if they wished. More work needs to be done, according to OpsGroup founder Mark Zee, but the Notam Sprint team’s efforts at least point the way to a solution.

NTSB Recommendation Results

The FAA did respond to the NTSB’s recommendations following the San Francisco near-collision and said, “We will continue to share our progress towards notam modernization with our aviation industry stakeholders through periodic briefings.” The agency also gave three private briefings to then-NTSB vice chairman Bruce Landsberg on Aug. 19, 2019, Dec. 19, 2019, and Nov. 12, 2020. On Dec. 13, 2022, the FAA briefed the industry-led Aeronautical Services Reform Coalition. Finally, the FAA promised to provide updates online, but the link it provided is now dead.

AIN contacted Landsberg to ask about the results of those briefings, and basically, nothing happened.

“I have been doing battle in this little corner for a quarter of a century,” he said, “and I feel like Charlie Brown and Lucy and the football [a cartoon where Lucy endlessly promises to let Charlie kick the football then lifts it at the last second, every time, so he misses] saying, ‘We’re going to fix it; this time we really mean it.’”

Landsberg flies his airplane frequently from Georgia to north of Washington, D.C., and complained of seeing notams in his preflight briefing that “have nothing to do with the flight. On my flights north, I routinely get something like laser lights at Disney World because it’s part of Jacksonville Center [airspace].” He admits that there is a slim possibility that, for some reason, he could end up having to divert to Orlando, but even so, he would ask controllers for help during such a critical situation and not worry about whether there is an unlighted crane at 200 feet agl 4.5 miles from the new destination airport.

“I was almost certain that after the incident in San Francisco [this would be fixed]. Had the Air Canada airplane actually landed on the taxiway, it probably would have been a bigger accident than Tenerife,” where two Boeing 747s collided on the ground as one was taking off in foggy conditions. While he wasn’t on the board when the incident occurred, the fact that the NTSB did a major investigation on an incident in which no one was injured and no damage occurred was significant. “They missed the tail [of one of the airplanes on the taxiway] by something less than 20 feet,” he said.

“It’s easy to pile on to the crew, but a number of factors went into it. I thought after that [incident], the notam business and whole system would start to make sense because we were within 20 feet of having a humongous fireball. That’s what triggered my request [to the FAA] as vice chairman, ‘How about a briefing?’”

Landsberg continued asking the FAA for help, despite the lack of progress evident during his briefings. He was also the industry co-chair of the General Aviation Joint Steering Committee. “I was asking, can we get some help on this, because this is not a friendly system at all.”

Over the years, Landsberg has seen congressional mandates and industry working groups try to tackle the notam problem. “And then nothing happens,” he said. “If you gave it to Google to sort things out, you’d have an answer in six months.”

There is no question that how notams are disseminated and organized is a fundamental problem, Landsberg said. He likes to quote former FAA associate administrator for aviation safety Nick Sabatini, who said about notams: “If everything’s important, nothing’s important. You can’t have everything hair-on-fire top priority because it gets lost in the clutter.”

As for notams’ hard-to-decipher contractions and all-capitals presentation, he added, “There are hundreds of contractions; some are obvious, and some are obscure. I like to remind my friends at the FAA that the teletype is not coming back and [the last little country in the world using a teletype] should not be wagging the aviation dog.”

Fundamentally, he explained, quoting Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw, “‘The greatest illusion about communication is the fact that it has taken place.’ That concept is absolutely correct. We get so bogged down in the process, we forget what this is all about: coming up with something to let pilots know about operationally pertinent items. If it’s an unlit something or other, if we’re day VFR, we don’t need to know it’s missing a couple of lights. We don’t need to know anything below 200 or 300 feet within three miles of an airport unless we’re flying a helicopter. We can parse these at a pretty basic level and probably eliminate 70% of the garbage.”

Task Force Meets Notam Act

It turns out that there has been progress on responding to the Notam Improvement Act of 2023. The industry task force formed to address the act’s mandate just released the results of its work, although the report was finalized on January 3.

According to the report's executive summary, “The Task Force’s mandate included identifying deficiencies and recommending improvements in the presentation and distribution of notams, focusing on user accessibility and security. The current management of notams faces challenges, including a high volume of notices that can obscure crucial information, complex formatting that may lead to misunderstandings, and the potential for critical data to be buried within lengthy messages.” The results include 41 “actionable recommendations.”

For some unexplainable reason, the report contains no mention of the work done by the OpsGroup’s Notam Sprint team, although its recommendations do capture some of the spirit of the Sprint team’s work.

The task force included FAA and industry people as well as subject matter experts (SMEs). Industry members came from the NBAA, AOPA, ALPA, AEEE, ACI-NA, A4A, NATCA, PASS, airlines, Boeing, Collins Aerospace, Universal Weather & Aviation, and the Ohio State University. SMEs included people from the Department of Defense, more airlines, The Weather Channel, and flight planning company Flightkeys. There were no representatives from electronic flight bag app companies such as ForeFlight.

In the 50-page report, the recommendations did address issues raised by the OpsGroup Notam Sprint team. There were five primary focus areas addressed by five workgroups covering: notam processes, standardization, human factors, FAA-industry engagement, and system resiliency, stability, and security.

Some of the notable recommendations include:

- The FAA should develop protocols that allow for third-party prioritization, sorting, and filtering of aeronautical information and attaching critical flags to datasets, enabling users to focus on essential datasets first.

- The FAA should, following the sunsetting of the U.S. notam system, update notam governance policy to allow for and begin transitioning tower light notam data out of the notam system and into its own digital aeronautical data application.

- The FAA should expand the provision of geospatial data to those (smaller) airports previously not surveyed to provide pilots with graphical displays of notams containing location-specific information and to enhance situational awareness.

- The FAA should work to ensure that notams are designed according to human factors principles that enhance both the clarity and criticality of information, while increasing users’ ability to process, comprehend, and retain the information. This ensures that the information is clear and highlights critical details, removing legacy text formatting (e.g. use of all caps or single-space notams). This approach will also help users better process, understand, and remember the information.

- Users, including pilots who receive notams via a company-issued flight packet, should be able to customize and search notam information (e.g., sort, filter, prioritize, display) based on their individual needs, and the system should allow for this customization through an interface that is intuitive and has clear navigation and search functionalities.

- The FAA should create a centralized, online, and publicly available portal containing all relevant aeronautical information. A thorough inventory of aeronautical information should be conducted collaboratively by the FAA and stakeholders to ensure that the portal is complete.

- The FAA should ensure that the notam system is designed with a sufficiently open architecture to allow for the flexible adaptation of new and emerging technologies.

- (Supporting detail) Use plain English instead of contractions/abbreviations. (AIN emphasis.)

There is much more to the report, and no assurance that its recommendations will be implemented. As well, the task force believes that its work, if completed, will satisfy the NTSB’s recommendations in A-18-024, which still haven’t been implemented by the FAA. The task force also urged that “A dedicated FAA/industry working group should be established within 180 days of the sunsetting of this Task Force to ensure continued collaboration and improvement of notams. This body should be comprised of a membership mixture similar to that which was outlined by Congress for this Task Force and should collaborate as the FAA initiates work to ensure that all notams contain actionable information, defined as operationally significant information that pilots and flight planners can assimilate easily, quickly, and accurately.”

However, the FAA recently announced that it is moving up the deployment of a modernized notam service to September. This will be months ahead of the agency's Internal target of the end of the year. CGI Federal, the selected contractor, now expects to deliver the Notam Modernization Service by July, putting it on pace to become operational in September.

Noting that more than four million notams are issued annually, the FAA said the modernization will facilitate a more efficient flow of data and stakeholder collaboration. Hosted in a secure site in the cloud, the service will be scalable. The FAA said it was also designed with resilient architecture, which is even more critical given outages that have occurred in recent years.

Note: AIN is using “notam” as a word per the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) definition: “A notice distributed by means of telecommunication containing information concerning the establishment, condition, or change in any aeronautical facility, service, procedure, or hazard, the timely knowledge of which is essential to personnel concerned with flight operations.”

On the night of July 7, 2017, the flight crew of Air Canada Flight 759, flying an Airbus A320, lined up with San Francisco International Airport’s Taxiway C instead of Runway 28R after being cleared to land. Four airliners were waiting on Taxiway C for takeoff, and the A320 kept descending toward them until it reached 100 feet agl and flew over the first airplane, then started a go-around. At its lowest point, the A320 reached 60 feet agl and was an estimated 10 to 20 feet above the second airplane in line before climbing away.

There was a notam for the closed parallel runway—28L. It was in the pilots’ flight release package and included in the airport’s ATIS flight information broadcast, which pilots must review prior to arrival. The closed runway notam was on page eight of a 27-page briefing package in a section titled “Runway” and came after 14 clearly less urgent notams. Six of these were for OBST CRANE, none of which intruded into the flight path for Runway 28R. Two were for taxilane closures, three for taxiway closures, and one for taxiway CL LGT U/S, which means “centerline lights unserviceable” in notam-speak.

After all of these less urgent notams, the Runway section listed five notams that looked like this:

INSERT PHOTO 1

Even though the critical runway closure notams came after a set of useless notams, the importance of the closed runways was highlighted by the word NEW in red. Otherwise, there was no ranking of these critical notams that might have signaled to the pilots that there was something important that needed their attention.

In follow-up interviews about the incident, the first officer stated that he could not recall reviewing the specific notam that addressed the runway closure. “The captain stated that he saw the runway closure information, but his actions (as the pilot flying) in aligning the airplane with Taxiway C instead of Runway 28R demonstrated that he did not recall that information when it was needed,” according to the NTSB report.

According to the NTSB, “Features of the Notam text emphasized the closure information, such as the use of bold font for the words ‘RWY’ and ‘CLSD’ and a ‘**NEW**’ designation in red font with asterisks before the Notam text, as shown in figure 10.98. However, this level of emphasis was not effective in prompting the flight crewmembers to review and/or retain this information, especially given the Notam’s location (toward the middle of the release), which was not optimal for information recall. A phenomenon known as ‘serial position effect’ describes the tendency to recall the first and last items in a series better than the middle items (Colman 2006).”

This is what ATIS Quebec looked like as received via the aircraft’s onboard aircraft communications, addressing, and reporting system (ACARS). In other words, the pilots didn’t listen to information Quebec on the KSFO ATIS radio frequency but read it as an ACARS transmission. (The yellow section highlighting the runway closure is from the NTSB report, not the way it looked to the pilots.)

ATIS Quebec

The report continued: “The ACARS message providing ATIS information Quebec, as displayed in the cockpit, was 14 continuous lines with all text capitalized in the same font. As shown in figure 11, the Notam indicating the Runway 28L closure appeared at the end of line 8 and the beginning of line 9. The uniform presentation of the ATIS information could have contributed to the flight crew’s oversight of the runway closure information.”

During a hearing on the incident, then-NTSB chairman Robert Sumwalt singled out what he called the “messed up” notam system.

Sumwalt claimed that the “crew didn’t comprehend the notams” and, as an example of the confusing notams pilots are faced with, read this complex entry from that same Air Canada flight’s briefing package, just one of the many for Toronto Pearson International Airport: “**72**YYZ 06.Jul.2017 1400z - 31.Jul.2017 2200z 1Y1247/17 TWY AK, TWY R BTN TWY B AND TWY AT, TWY B BTN TWY B1 AND TWY R NOT AUTH TO ACFT WITH WINGSPAN GREATER THAN 214 FT.”

“Why is this even on there?” he asked. “That's what notams are: they’re a bunch of garbage that no one pays any attention to,” adding that they’re often written in a language that only computer programmers would understand.

Sumwalt also relayed a recent experience he had flying the jumpseat into North Carolina’s Charlotte Douglas International Airport, saying, “There were pages and pages and pages of notams, including one for birds in the vicinity of the airport…When are there not birds in the vicinity of an airport?”

The NTSB issued six safety recommendations to the FAA after the Air Canada incident, one of which—A-18-024—was to develop a “more effective presentation of flight operations information to optimize pilot review and retention of relevant information.” So far, that recommendation’s status remains “Open—acceptable response.” This means that the FAA has indicated it would, but has yet to comply with the recommendation, eight years after the near-collision and seven years after the NTSB recommendation.

In fact, notams are not supposed to be used for information that might be considered normal—for example, birds in the vicinity of an airport. Such a notam provides no useful information because birds move around, and there is no way to assess the level of risk involved, other than the normal watch for potential hazards such as birds.

According to an FAA presentation for airport managers, “A notam is a notice containing information essential to personnel concerned with flight operations but not known far enough in advance to be publicized by other means. Notams concern the establishment, condition, or change of any component (facility, service, procedure, or hazard) in the NAS [National Airspace System]. They must state the abnormal status of a component of the NAS—not the normal status.”

There is plenty of guidance for those responsible for creating notams. The foundational instructions come from the ICAO, which sets standards for member states to implement. ICAO’s guidance still advises the use of contractions and capital letters, which are leftovers from the days of teletype machines when bandwidth was extremely limited.

For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, ICAO and the world’s aviation authorities have continued with this protocol. The FAA requires that “Contractions and abbreviations designated for ICAO usage as specified in FAA Order JO 7340.2, Contractions, and ICAO Document 8400, ICAO Abbreviations and Codes, must be used in the notam system. When an ICAO−usage contraction is not available, plain text is required, except for the list of differences in Appendix C.”

ICAO’s documentation lists common terms and their coding information and “uniform abbreviated phraseology” to help those who submit notams. However, this isn’t a perfectly clear process, and there is room for confusion.

For example, the contraction “act” can mean two things in ICAO-speak: when used by itself, it means “activated,” but when preceded by the word “volcanic,” it means “activity.” To add inconsistency, the word “deactivated” is not abbreviated to something like “deact” but is spelled out in full. A word like “canceled” is contracted to “cnl,” which is hardly intuitive. Yet “prohibited to” is spelled out instead of contracted to something like “phbto.” Runway centerline lights are “rcll” when other mentions of lights use the contraction “lgt” like “twy cl lgt” for taxiway centerline lights.

The FAA seems to think that this is a good idea. From the notam presentation: “Notams have a unique language characterized by the use of specialized contractions. Contractions are imperative to the notam structure because they make communication more efficient and allow computer systems to parse important words.” It is not clear how the inconsistent use of contractions makes it easier to parse important words.

Notams are so important—even though many are not considered essential for aviation safety—that the FAA paused domestic airline departures for an hour and a half when the U.S. notam system shut down on Jan. 10, 2023. The problem was due to a contractor who “unintentionally deleted files while working to correct synchronization between the live primary database and a backup database,” according to the FAA, which added, “The FAA made the necessary repairs to the system and has taken steps to make the notam system more resilient.” Yet since then, the FAA had to inject delays into the system on Feb. 1, 2025, due to another outage, this time reportedly a hardware issue, and again on March 22.

Thousands of new notams are generated each day, and tens of thousands are in various databases. Efforts to make the notam system work better frequently mention starting with those who write the notams, claiming that the system’s problems originate with poorly coded Notams or ones that simply shouldn’t have been submitted in the first place.

ICAO points out on its NOTAMeter website that simply removing old and obsolete notams would instantly reduce the number of notams in the database by 20%. NOTAMeter is a tool to analyze the age of notams submitted by the 193 ICAO member states.

Unfortunately, the NOTAMeter tool is not current. The last date for which data was published is July 1, 2023, and at the time, it said there were 34,733 notams in the world. A list shows how many old notams exist for each state, with some of the highest numbers from countries in Africa. Yet even the U.S. and France have a significant number of old notams, 13% and 13.3%, respectively.

ICAO has launched a notam improvement project, with the following goals intended to help civil aviation authorities and data originators: using ICAO’s NOTAMeter to analyze a state’s notams, identify old notams and cancel or replace them, or simply update aeronautical information products; delete non-compliant notams; come up with procedures to prevent inputting of non-compliant notams; and examine training and competency of notam personnel.

Notably, the above attempts to address the problem from the notam submission angle. Some in the industry thought there might be a better way.

OpsGroup to the Rescue

In February 2023, after the U.S. ground stops due to the Notam system failure, OpsGroup convened a team to answer the question, “What do pilots want” from notams. In May, OpsGroup brought together 300 people for a “Notam Sprint,” a five-day effort to “Design a prototype system to post-process notams, tag them, summarize them, and then sort/filter into a newly designed briefing package.”

One of the team’s earliest realizations was that it would be impossible to fix the problem from the bottom up just by brute-forcing the correct submission of notams and by trying to get notam submitters to do a better job. The real challenge—and the resulting epiphany—was figuring out how to make more effective use of the existing notam system.

This addresses a fundamental truth about the slow notam improvement efforts by CAAs: anyone is free to do with notams what they will. CAAs can create their own improved notam systems, building off the existing database. Electronic flight bag app developers can build notam transcription and organization features into their apps, putting the important notams at the top of the list, highlighting them, and turning them into readable plain English, even using uppercase and lowercase letters that are proven to be far easier to read than all caps. ForeFlight, for example, does this with notams that are tied to specific airports.

An airline or flight operation can even use software tools that OpsGroup helped develop to run their own notam improvement programs. A key result of the Notam Sprint was the creation of a categorization system that puts important notams at the forefront and delegates nearly useless ones (“dark notams,” as OpsGroups calls them) into an appendix.

“It doesn’t solve it at the back end (the notam office),” OpsGroup explained, “but it doesn’t need to, anymore. Until this year, we were all convinced that the only way to fix notams was to change the way notams are issued by notam officers, perhaps adding a tag to each one so we could organize them better. But AI has launched a cannonball of change into the aeronautical information sphere. Notams are just the start of the change we can expect to see.”

For the Notam Sprint testing, the team created an application programming interface that demonstrated the benefits of its approach, and airlines and aircraft operators could build on that if they wished. More work needs to be done, according to OpsGroup founder Mark Zee, but the Notam Sprint team’s efforts at least point the way to a solution.

OpsGroup Notam Sprint

NTSB Recommendation Results

The FAA did respond to the NTSB’s recommendations following the San Francisco near-collision and said, “We will continue to share our progress towards notam modernization with our aviation industry stakeholders through periodic briefings.” The agency gave three private briefings to then-NTSB vice chairman Bruce Landsberg on Aug. 19, 2019, Dec. 19, 2019, and Nov. 12, 2020. On Dec. 13, 2022, the FAA briefed the industry-led Aeronautical Services Reform Coalition. Finally, the FAA promised to provide updates online, but the link it provided is now dead.

AIN contacted Landsberg to ask about the results of those briefings, and basically, nothing happened. “I have been doing battle in this little corner for a quarter of a century,” he said, “and I feel like Charlie Brown and Lucy and the football [a cartoon where Lucy endlessly promises to let Charlie kick the football then lifts it at the last second so he misses] saying, ‘We’re going to fix it; this time we really mean it.’”

Landsberg flies his airplane frequently from Georgia to north of Washington, D.C., and complained of seeing notams in his preflight briefing that “have nothing to do with the flight. On my flights north, I routinely get something like laser lights at Disney World because it’s part of Jacksonville Center [airspace].

“I was almost certain that after the incident in San Francisco, had the Air Canada airplane actually landed on the taxiway, it probably would have been a bigger accident than Tenerife,” where two Boeing 747s collided on the ground as one was taking off in foggy conditions. While he wasn’t on the board when the Air Canada incident occurred, the fact that the NTSB did a major investigation on an incident in which no one was injured and no damage occurred was significant. “They missed the tail [of one of the airplanes on the taxiway] by something less than 20 feet,” he said.

“I thought after that [incident], the notam business and whole system would start to make sense because we were within 20 feet of having a humongous fireball.”

Over the years, Landsberg has seen congressional mandates and industry working groups try to tackle the notam problem. “And then nothing happens,” he said.

How Notams are disseminated and organized is a fundamental problem, Landsberg said. He likes to quote former FAA associate administrator for aviation safety Nick Sabatini, who said about notams: “If everything’s important, nothing’s important. You can’t have everything hair-on-fire top priority because it gets lost in the clutter.”

As for notams’ contractions and all-capitals presentation, he added, “There are hundreds of contractions; some are obvious, and some are obscure. I like to remind my friends at the FAA that the teletype is not coming back.”

Fundamentally, he explained, “We get so bogged down in the process, we forget what this is all about: coming up with something to let pilots know about operationally pertinent items. If it’s an unlit something or other, if we’re day VFR, we don’t need to know it’s missing a couple of lights. We can parse these at a pretty basic level and probably eliminate 70% of the garbage.”

Task Force Meets Notam Act

There has been progress on responding to the Notam Improvement Act of 2023. The industry task force formed to address the act’s mandate just released the results of its work, although the report was finalized on January 3.

The task force found: “The current management of notams faces challenges, including a high volume of notices that can obscure crucial information, complex formatting that may lead to misunderstandings, and the potential for critical data to be buried within lengthy messages.” The report includes 41 “actionable recommendations.”

The task force included FAA and industry people as well as subject matter experts (SMEs). Industry members came from associations, airlines, other companies, and academia.

In the 50-page report, the recommendations did address issues raised by the OpsGroup Notam Sprint team. There were five primary focus areas addressed by workgroups covering: notam processes, standardization, human factors, FAA-industry engagement, and system resiliency, stability, and security.

Some of the notable recommendations include:

The FAA should develop protocols that allow for third-party prioritization, sorting, and filtering of aeronautical information and attaching critical flags, enabling users to focus on essential data first.

The FAA should, following the sunsetting of the U.S. notam system, begin transitioning tower light notam data out of the notam system and into its own digital aeronautical data application.

The FAA should expand the provision of geospatial data to smaller airports previously not surveyed to provide pilots with graphical displays of notams containing location-specific information.

The FAA should ensure that notams are designed according to human factors principles to increase the ability to process, comprehend, and retain the information.

Users, including pilots who receive notams via a company-issued flight packet, should be able to customize and search notam information based on their individual needs, and the system should allow for this customization through an intuitive interface.

The FAA should create a centralized, publicly available portal containing all relevant aeronautical information.

The FAA should ensure that the notam system is designed with open architecture to allow for the adaptation of new and emerging technologies.

Use plain English instead of contractions/abbreviations.

There is much more to the report. However, there is no assurance that its recommendations will be implemented. The task force believes that its work, if completed, will satisfy the NTSB’s recommendations in A-18-024. The task force also urged that “A dedicated FAA/industry working group should be established within 180 days of the sunsetting of this Task Force to ensure continued collaboration and improvement of notams. This body…should collaborate as the FAA initiates work to ensure that all notams contain actionable information, defined as operationally significant information that pilots and flight planners can assimilate easily, quickly, and accurately.”