Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 403502

Safety Culture may be one of the hottest, yet least understood, topics in aviation safety. What does it mean? Often when we talk about aviation safety, we’re talking about physical safety. We’re talking about transporting people or boxes from A to B without incident.

But a lack of incident isn’t the only metric for a good safety culture.

Well-established Safety Systems

Safety Management Systems (SMS) is a valued and established set of protocols and processes to enhance the safety of an organization. From it, the industry has learned that trust is the fundamental building block for a positive safety culture. But, how do we build trust?

Crew Resource Management (CRM) implores us to use effective communication and all available resources. But, it doesn’t tell us how to effectively communicate nor does it explain how to maximize our human connection. Many pilots are comfortable with the tactical style of communication; we train for that in the simulator. Yet that style of communication does little to foster human connection, empathy, or inclusion.

The protocols, audits, and checklists of SMS and CRM have provided teams with important tactics for upholding physical safety. However, these systems are left vulnerable because they fail to educate on the “human” aspect of human factors training.

Genuine human factors training would include elements of neurobiology, cognitive science, epistemology, emotional intelligence, and leadership strategy. Each one of these facets would provide insight into how humans think, respond, and interact. Ultimately, we would learn that all humans want to be seen, heard, and valued. We want to feel safe to be our authentic best selves while also feeling a sense of belonging as a valued team member.

On Being Seen

Think about this sentence: “The pilot was unhappy with the catering.”

What image do you get? My brain thought of a middle-aged, white, male pilot in the left seat being handed his lunch that he didn’t like. My brain visualized the flight deck and I could see that the airplane was in cruise flight. From the one sentence, my brain filled in a lot of details.

Now, let me change one thing about the sentence. Think about this one:

“The flight attendant was unhappy with the catering.”

Now, what image do you get? I visualized a young female flight attendant hunched over poorly packaged food that she would later have to serve. I could see that the airplane was on the ground and she was in the galley sorting through catering boxes.

Take a moment and compare the images you got from the two sentences. By changing just one thing about the sentence (flight attendant versus pilot) my brain created a completely different story. And, I’m guessing yours did too. Our brains are constantly filling in a lot of details even though those details weren’t part of the original sentence. That’s called bias, and it’s normal.

Our brains receive 11 million bits of information per second. But, we can only process about 40 bits per second, which means 99 percent of the information we receive, we cannot process consciously. Our brain makes mental associations and forms prototypes as a way of processing data more quickly. These subtle cues and associations were important in our evolution. They helped our brains make quick decisions on whether someone was a friend or foe and helped trigger the fight-flight-freeze response.

The prototypes and mental associations we unconsciously create can influence how we view other people. Our mental models try to tell us how people should think or should act. But, we know that not everyone fits perfectly into our subconsciously created prototypes. So if we don’t question our own bias, we may end up perpetuating antiquated models or outdated stereotypes. We can do this by approaching the topic with an open mind and curiosity. In meetings, is there a certain type of person you cut off more frequently? Or a certain type of person you give more eye-contact to? How about a type of person you’d rather mentor, promote, or hire? If so, why?

We want to feel seen. But the first step in seeing others is to admit we all have biases.

On Being Heard

When we feel safe to show up as our authentic best selves, we have a high level of psychological safety.

Psychological safety is defined as “being able to show and employ one’s self without fear of negative consequences of self-image, status, or career.” It means we feel comfortable speaking up with our original thoughts even when they fall outside of the groupthink model.

Psychological safety is fundamental to safety culture. When we don’t feel safe to be ourselves or speak up, our brain shifts from critical thinking and logical processing to defense mode. When an individual senses danger (real or perceived, physical or emotional), our amygdala gets triggered. The amygdala is the part of our brain responsible for triggering the fight-flight-freeze response when a threat is observed. When triggered, our cognitive functioning is impaired. Our attention shifts from pro-safety team behavior to one of defensive self-protection. Over time, low psychological safety also affects us physiologically through stress, burnout, low morale, and fatigue.

The incidents that go unreported, the disgruntled employee that overlooks protocols, the subtle noncompliance, and the costly employee burnout all lead to a reduction in safety and a deterioration of safety culture.

Conversely, psychological safety enhances safety culture because it allows people to ask tough questions and share their mistakes without fear of embarrassment or punitive repercussions. SMS refers to this culture as a “just” culture. However, psychological safety, built on trust, is the keystone to establishing a just culture.

Psychological safety enhances safety because it creates a learning environment where employees feel engaged and free to express themselves. It is fueled by group trust and is paramount to healthy, high-functioning teams as it allows employees to feel heard.

On Being Valued

We hear a lot about inclusive leadership strategies. Forbes found that inclusive groups were more productive and made better decisions 87 percent of the time. The business case has already been made: inclusive leadership leads to more creativity, increased productivity, and a higher level of safety. Yet, how do we create inclusive teams? Part of the puzzle rests in understanding an individual’s unique experiences and by looking at our differences as an asset.

Many people believe that aviation is a meritocracy, which means that everyone is on an equal playing field. In a meritocracy, the harder you work, the more successful you become. We all want to believe in that type of system because it sounds fair and it embodies the American spirit. Unfortunately, it’s far too simplistic and negates recognizing the individual hurdles each person experiences.

Let’s think about this. You fly your G650 from LAX to TEB. That flight takes four hours. Now, you turn around a fly back to LAX. This leg takes five hours. We all understand these phenomena as headwinds and tailwinds. You can’t argue with physics.

The same concept can be applied to individuals. Let’s say we have two pilots that start flight training at the same time. Pilot A is not financially burdened. This pilot can take extra classes to finish sooner, fly whenever the weather cooperates, and attend after-school networking events. Meanwhile, Pilot B works after school to pay for flight training. Pilot B cannot take extra classes, has a less malleable schedule, and misses those evening networking events.

Pilot B is fighting a relative headwind while Pilot A is enjoying a relative tailwind. Pilot A completes flight training more quickly, makes more connections, and can establish relatively ahead within the industry because of those tailwinds. There’s nothing wrong with this, but it’s important to understand that some people have tailwinds and some have headwinds.

Now, a decade later Pilot A and Pilot B apply for the same job. Likely, the resume shows Pilot A completed flight school quickly, has more flight time, and has more connections within the industry. Doing a quick resume comparison without understanding their personal headwinds and tailwinds, you might want to hire Pilot A. But, maybe Pilot B could be a better choice because they had to work harder fighting those headwinds.

We must understand that some people overcome significant headwinds while others enjoy tailwinds. And, despite how much we want it to be, our industry is not a meritocracy. These relative headwinds and tailwinds help create our uniqueness and authentic selves. Understanding these individual characteristics help leaders create cohesive teams where people feel valued as individuals while also creating a sense of belonging in an inclusive group.

Safety Culture—A Collective Term

Culture is a collective term, meaning a singular individual cannot create it. Culture is observed through the social norms and behaviors of the individuals comprising a group. Within aviation’s SMS, we can measure the culture quantitatively through safety reports and qualitatively through employee surveys.

The culture of the team is dependent on the psychological safety of the individuals that comprise it. Employees who do not feel comfortable speaking up will not fill out safety reports. Those that do not feel valued will not honestly answer the qualitative surveys. Burnout and low morale are direct indicators of a poor safety culture.

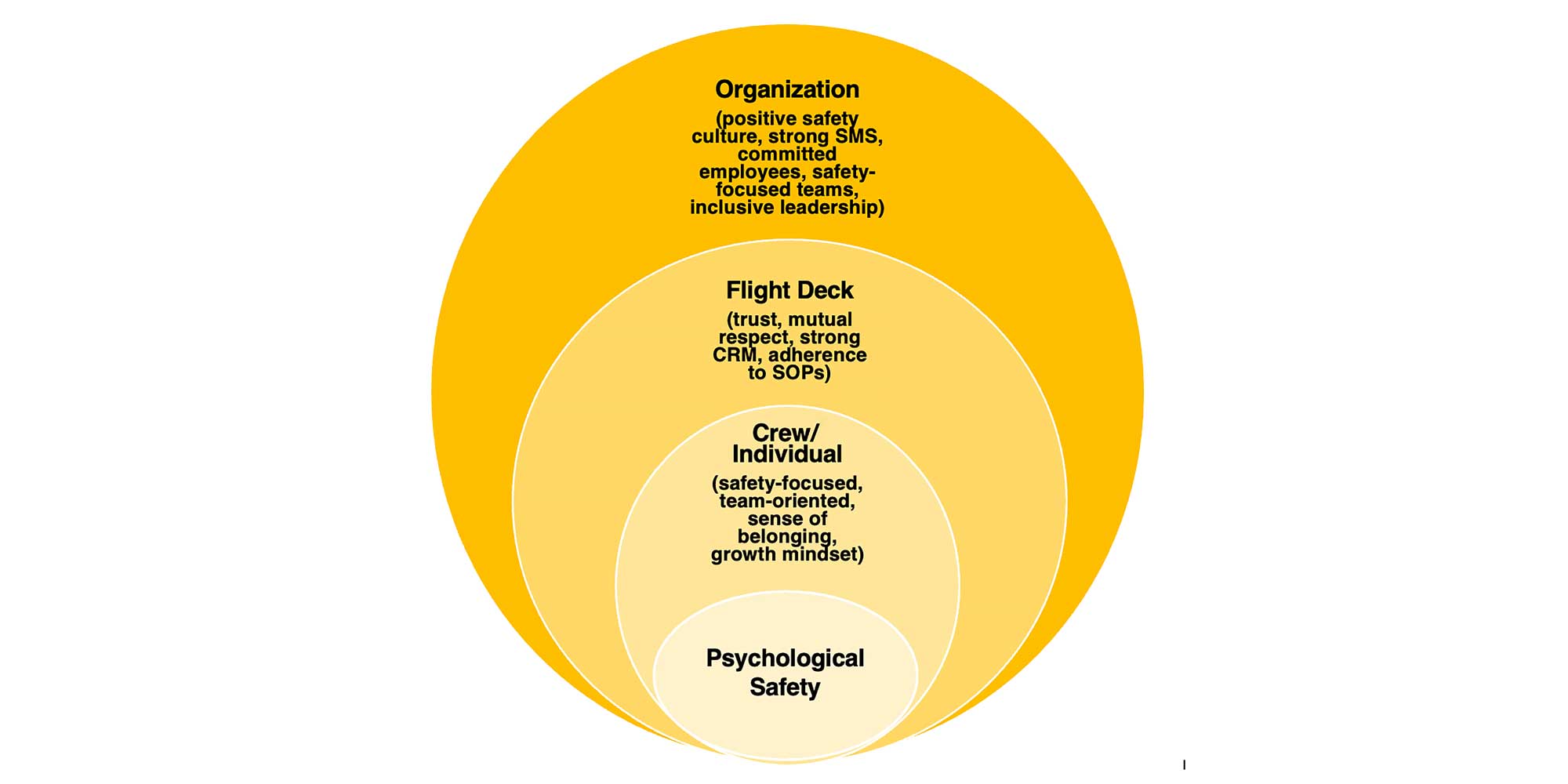

The building blocks of your organization’s safety are comprised of protocols, processes, and most importantly, the individuals upholding them. When one building block crumbles from an employee’s low psychological safety, the whole team’s safety is reduced. No person, title, or position is exempt from the negative effects of low psychological safety. Its relevance is prolific at all levels.

The micro-culture of your organization or the macro-culture of the industry lies heavily on the psychological safety of the individuals that comprise it. Creating psychological safety is strongly dependent upon leadership; and, it is critical for high-performing individuals and teams. Trust is the bedrock of psychological safety. Leaders can build trust by utilizing inclusive leadership strategies. This includes admitting we all have biases, understanding employees' headwinds and tailwinds, and valuing employees for their uniqueness. We must find strength in our differences to maximize the benefits of inclusive leadership and create a genuine positive safety culture.

Safety culture is not a singular, check-the-box element of SMS. It is something to improve upon daily. The tone for the organization is set by leadership but everyone plays a role. As an industry, we invest in new technologies, pilot training, and emergency training. We are always learning and always striving to do better. We can do this collectively by investing in aviation's most important asset—its human capital. It starts with a deep dive into more comprehensive human factors training.

Safety Culture may be one of the hottest, yet least understood topics in aviation safety.

Safety Management Systems (SMS) is a valued and established set of protocols and processes to enhance the safety of an organization. From it, the industry has learned that trust is the fundamental building block for a positive safety culture. But, how do we build trust?

Crew Resource Management (CRM) implores us to use effective communication and to use all available resources. But, it doesn’t tell us how to effectively communicate nor does it explain how to maximize our human connection. Many pilots are comfortable with the tactical style of communication; we train for that in the simulator. Yet, that style of communication does little to foster human connection, empathy, or inclusion.

The protocols, audits, and checklists of SMS and CRM have provided teams with important tactics for upholding physical safety. However, these systems are left vulnerable because they fail to educate on the “human” aspect of human factors training.

Genuine human factors training would include elements of neurobiology, cognitive science, epistemology, emotional intelligence, and leadership strategy. Each one of these facets would provide insight into how humans think, respond, and interact. Ultimately, we would learn that all humans want to be seen, heard, and valued.

On Being Seen

Our brains receive 11 million bits of information per second. But, we can only process about 40 bits per second, which means 99% of the information we receive, we cannot process consciously. Our brain makes mental associations and forms prototypes as a way of processing data more quickly. These subtle cues and associations were important in our evolution. They helped our brains make quick decisions on whether someone was a friend or foe and helped trigger the fight-flight-freeze response.

The prototypes and mental associations we unconsciously create can influence how we view other people. These associations can influence how we think about others. Our mental models try to tell us how people should think or should act. But, we know that not everyone fits perfectly into our subconsciously created prototypes. So, if we don’t question our own bias, we may end up perpetuating antiquated models or outdated stereotypes.

We want to feel seen. But, the first step in seeing others is to admit we all have biases.

On Being Heard

When we feel safe to show up as our authentic best selves, we have a high level of psychological safety.

Psychological safety is defined as, “being able to show and employ one’s self without fear of negative consequences of self-image, status, or career.” It means we feel comfortable speaking up with our original thoughts even when they fall outside of the groupthink model.

Psychological safety is fundamental to safety culture. When we don’t feel safe to be ourselves or speak up, our brain shifts from critical thinking and logical processing to defense mode. When an individual senses danger (real or perceived - physical or emotional), our brain triggers the fight-flight-freeze response. When triggered, our cognitive functioning is impaired. Our attention shifts from pro-safety team behavior to one of defensive, self-protection.

The incidents that go unreported, the disgruntled employee that overlooks protocols, the subtle noncompliance, and the costly employee burnout all lead to a reduction in safety and a deterioration of safety culture.

Conversely, psychological safety enhances safety culture because it allows people to ask tough questions and share their mistakes without fear of embarrassment or punitive repercussions. It creates a learning environment where employees feel engaged and free to express themselves. It is fueled by group trust and is paramount to healthy, high-functioning teams as it allows employees to feel heard.

On Being Valued

We hear a lot about inclusive leadership strategies. Forbes found that inclusive groups were more productive and made better decisions 87 percent of the time. The business case has already been made: inclusive leadership leads to more creativity, increased productivity, and a higher level of safety. We can create this environment by understanding an individual’s unique experiences and looking at our differences as an asset.

Many people believe that aviation is a meritocracy, which means that everyone is on an equal playing field. In a meritocracy, the harder you work, the more successful you become. We all want to believe in that type of system because it sounds fair and it embodies the American spirit. Unfortunately, it’s far too simplistic and negates recognizing the individual hurdles each person experiences.

Let’s say two pilots start flight training at the same time. Pilot A is not financially burdened. This pilot can take extra classes to finish sooner, fly whenever the weather cooperates, and attend after-school networking events. Meanwhile, Pilot B works after school to pay for flight training, has limited time to fly, and misses those evening networking events.

Pilot B is fighting a relative headwind while Pilot A is enjoying a relative tailwind. Pilot A completes flight training more quickly, makes more connections, and can establish relatively ahead within the industry because of their tailwinds. There’s nothing wrong with this, but it’s important to understand that some people have tailwinds and some have headwinds.

These relative headwinds and tailwinds help create our uniqueness and authentic selves. Understanding these individual characteristics help leaders create cohesive teams where people feel valued as individuals while also creating a sense of belonging in an inclusive group.

Safety Culture—A Collective Term

Culture is a collective term, meaning a singular individual cannot create it. Culture is observed through the social norms and behaviors of the individuals comprising a group.

The micro-culture of your organization or the macro-culture of the industry lies heavily on the psychological safety of the individuals that comprise it. Leaders can build trust by utilizing inclusive leadership strategies. This includes admitting we all have biases, understanding employee's headwinds and tailwinds, and valuing employees for their uniqueness. We must find strength in our differences to maximize the benefits of inclusive leadership and create a genuine positive safety culture.

Safety culture is not a singular, check-the-box element. It is something to improve upon daily. The tone for the organization is set by leadership but everyone plays a role. As an industry, we invest in new technologies, pilot training, and emergency training. We are always learning and always striving to do better. We can do this collectively by investing in aviation's most important asset—its human capital. It starts with a deep dive into genuine human factors training.