Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 405076

Twenty years ago when the 9/11 attacks devastated the world's economy and plunged the aviation industry into turmoil, National Business Aviation Association (NBAA) staffers joined together to help tackle the unprecedented challenges faced by the business aviation industry, both in the immediate aftermath and for the longer term.

Jo Damato

In July 2001, Jo Damato, now the senior v-p of education, training, and workforce for NBAA, had joined the association from Executive Jet Management to fill a newly created role: staffing a general aviation desk at the FAA Command Center.

That desk was years in the making, first proposed in 1998 at a peak time of airline delays. Government officials thought it might be a good idea to have a voice from the growing business aviation sector as well. Damato described those first few months as “quietly drinking from a fire hose,” trying to get up to speed on the inner workings of the heart of the nation’s air traffic control system. Yet people at the center weren’t quite up to speed on business aviation either.

“Nobody was engaging with me and I was so young. I was still learning how to engage with people, especially at such a mature facility with seasoned air traffic control professionals.” The managers at the desk held by the then-Air Transport Association (ATA), now Airlines for America (A4A), took Damato under their wing and helped her establish her presence at the facility. “They were fantastic,” she said.

By the time September 11 rolled around that year, they were swapping coffee runs. Her ATA counterpart said he would get the coffee and Damato would watch over morning calls with ATC.

But then there was a “commotion” at the Northeast desk. “I didn’t know what it was, but I knew we’d better hold off on our coffee.” The staff was following a flight that they thought had likely been hijacked. “I don't want to minimize this, but it played out as something very interesting is happening right now, but not something terrifying,” she said. But then everyone in the room realized that there may be more than one thing happening, particularly since there was no contact with the pilots.

“It got quiet and everybody was on alert very quickly…and then a gasp from the floor. It was clear that an airplane had made contact with the [World Trade Center],” she said. Initially, "no one was thinking anything more than this is a horrible tragedy and what could have happened on an airplane that created something like that. I think assumptions outside the Command Center were that it was likely a very small aircraft." When the second airplane went in, Damato said, "I was 20 feet maybe from the man who was in charge of the floor that day. And he said, ‘Shut it down…nothing in or out.’ And very quickly [the national airspace system] was shut off.”

Incidentally, the national operations manager who made that call, Ben Sliney, was a veteran air traffic controller, but on his first day as manager of the center. Sliney, who described that morning during a forum held by the University of Texas at Dallas and aired by C-Span, said after the second aircraft hit the tower, which he saw on screens inside the center airing CNN, they knew, “This wasn’t the usual hijack by some deranged individual, but that this was a concerted attack by a group of people and America was under attack.”

Jack Olcott

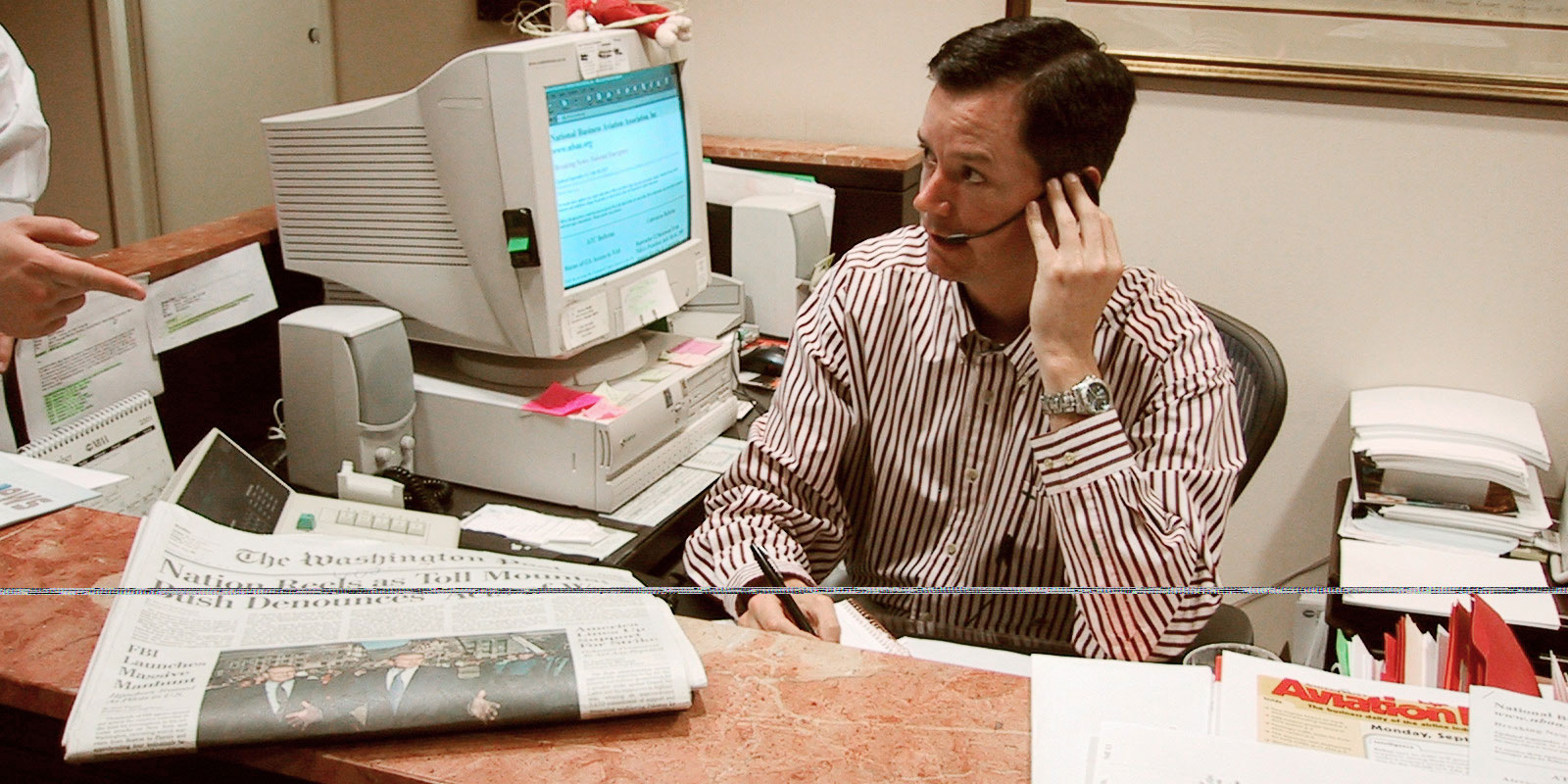

Then-NBAA president Jack Olcott had arrived early into the offices on the corner of 18th and M Street on the morning of 9/11. Olcott said he usually tried to get in around 7 a.m. to avoid the traffic restrictions and the general gnarl that occurs during rush hour in Washington, D. C. The day appeared to be typical until he received a call from NBAA’s head of the government affairs office, Pete West, and was told: “Turn on your TV. An airplane just hit the World Trade Center.”

Olcott said his first thought was some general aviation airplane had deviated off course from along the Hudson River and hit the 110-story building. “And my thoughts were all like others'. That's a shame; it's a tragedy. And I suspect, there'll be a lot of finger-pointing about general aviation.” He turned on the television and saw the plumes of smoke coming out of one of the towers. “While I was watching, another airplane, obviously an airliner, hit the remaining tower. It was clear that this was no random accident. This was something quite significant. After that event, things unfolded very rapidly.”

Doug Carr

During this time Doug Carr, now senior v-p of safety, security, sustainability, and international operations for NBAA, had received a call from the office alerting him that a small aircraft had hit the World Trade Center.

Carr headed into the office while running through in his mind a response to this aircraft crash because even with a small airplane, he knew it would be front-page news. “I'm thinking what's the weather looking like and where did they leave from? I'm trying to put together the pieces in my head about that and things I know we're going to be asked about.”

He took the George Washington Parkway to head towards the office, and “I'm driving by the Pentagon and the third airplane goes in and the fireball, and all of that happens.” Drivers on the opposite side of the road that parallels the Potomac River came to a complete stop. “Nobody knew what to do, seeing what just happened.” But Carr knew that the situation was grave and journeyed into the office where the team assembled to put the pieces together.

The Aftermath

The moment had reverberated throughout NBAA, as it did the entire aviation industry and the nation. And it reshaped security from the government's standpoint. At the time there was no presidential cabinet called the Department of Homeland Security. Nor was there was an agency called the Transportation Security Administration. The FAA handled aviation security in-house, working with outside agencies.

Since then, the business and general aviation industry has seen security protocols evolve over the years and new and lasting requirements and restrictions implemented. These include the advent of the Twelve-Five Standard Security Program for air charters, the Alien Flight Student Program for international flight training candidates who wish to train inside the U.S., and the increased use of no-fly zones and temporary (sometimes permanent) flight restrictions with “gateway airports.”

Business aviation still can’t fly into Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport without an armed security officer aboard, an approved DCA Access Standard Security Program, and vetting through a gateway. A Special Flight Rules area outer circle and Flight Restricted Zone inner circle capturing the “Maryland 3” airports (Hyde Field, Potomac Airfield, and College Park Airfield) remain in place. So too do ongoing restrictions over Disney parks, sporting events, and certain areas where the President travels.

In addition to dealing with a new department and agency stood up in the aftermath of 9/11, business aviation and general aviation leaders have had to deal with agencies, such as the Secret Service, that they had not had interactions with before just to conduct operations.

But looking back, Olcott said having the resources in place to mobilize quickly was critical for not only NBAA but the industry at large, enabling them to weather through the turmoil of the time and its aftermath. And the measures that are still in place now are a far cry from some of the proposals, and initial restrictions put in place in the immediate aftermath.

Information Chain

Damato said immediately after the attacks, ATC personnel turned to her and the ATA manager and told them to start talking to their members, make sure they knew who is on their airplanes, and if they haven’t gotten into the air, don’t. They are not getting there. If they had, find a way to get on the ground. She called NBAA headquarters, where she had not even been yet because she was so new on the job, and had to identify herself, reach Olcott, and coordinate with her immediate manager Bob Lamond, now retired but who was director of air traffic at the time. Lamond headed right to the Command Center and worked with Damato through the time.

She realized since NBAA then had a presence at the Command Center, they were considered essential personnel and allowed to stay. “I think that if we had not finally staffed that position, I'm not even sure we would've gotten into the facility now…and I'm so proud of what the team has been doing now for 20 years there.”

At headquarters, NBAA staff turned the board room into a command center and brought in phones and hooked up screens. Then the calls poured in. Many people called to ask how NBAA could get their flight in the air. “We were getting calls literally from movie stars and their flight operations saying, ‘Hey, I've, got a really important thing in Europe. I need to leave tonight. You guys need to help me get out because this thing tomorrow in Europe is really important.’”

NBAA staff had a difficult message to deliver: “Sorry, you must have heard the airspace is closed. We just had a terrorist attack. I think you're going to need to find other plans.”

At the same time, NBAA was trying to track down the handful of the association’s advanced staff that were headed to New Orleans where they were to hold their annual convention within a week. On September 12, however, the board agreed to postpone the convention and it was rescheduled for later in the year. By the evening of 9/11, NBAA was able to track down those staff and ensure their safety.

Along with having a spot at the Command Center, another factor worked in NBAA’s favor: it had recently launched a website. Olcott estimated that the website had only been fully live for about six weeks or so before then.

“Back then,” Carr recalled, “websites didn’t have the functionality they do today. They were very text-based.” To streamline and reduce the burden on the services, NBAA stripped out all of the graphics and turned it into a means to continually update members. Lamond and Damato would call in information and Jason Wolf, who is senior director of information architecture for NBAA and headed up the newly established website at the time, would then post the details.

“Our website became a critical piece of communication capability for us,” Carr said. “We sent everything we could to the website. We probably would not have been nearly as effective if we didn't have the website and the ability to turn it into this massive repeater for the information that we knew.”

In the years since, that website and others throughout the industry have become a critical conduit for the industry, particularly throughout the pandemic when the environment has shifted fairly quickly.

“I think it really solidified the value of a website in times like this, with just trying to keep people up to speed on what's going on with massive amounts of information,” he added.

“NBAA became the one conduit for communicating what was happening to the flight departments within business aviation. It was really quite impressive,” agreed Olcott.

Business Aviation: the Big Unknown

At the same time, though, the aftermath shed light on how little people outside of the industry knew about business and general aviation.

On the positive side, despite the initial grounding in the aftermath, business aviation was still able to step up on a limited basis. “We became useful,” Damato said, noting the association was getting a number of questions about what business aircraft could do. Business aircraft were called in to fly in special footpads for search dogs, to help with telecommunications companies that had just lost infrastructure, and to fly blood to where it was needed, among other missions. “There were a whole bunch of unique one-offs that business aviation was able to satisfy because we have resources," Carr said. "They weren't going anywhere, and we just needed a go-ahead from the government to say your flight has been cleared to go. And that's where the Command Center folks really starting to shine in terms of helping to facilitate those kinds of missions."

Once Command Center officials learned more about NBAA and business aviation, then the questions came: “Can you explain [Part] 91 to us? Can you explain 135 to us?” Damato said these were key questions because this information was being taken into consideration as the notams were being developed for operations in the aftermath.

Business Aviation as the Threat

“There were various study groups within government saying, well, we can't let business aviation fly because we really don't know what's in the airplanes. Then there was a thought that we can't let charter up. Why? Because the bad guy may charter a plane,” Olcott said. “So, there were a lot of thought groups, finding reasons why everything except the airlines and the military should be grounded.”

The Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), in a retrospective it wrote for the 10-year anniversary of 9/11, noted that its efforts to restore general aviation flight had to start immediately after the attacks. “Two days after the FAA grounding, limited airline service was restored, and soon after that, the Bush administration announced that the ‘U.S. aviation system has been restored.’ But general aviation was still grounded, and, in horror, we realized GA was taking the brunt of the fear the attacks had engendered. Were small airplanes now the terror of the skies?” AOPA had asked in an article written by Julie Summers Walker.

Olcott said the general aviation community coalesced to “fight the good fight” with numerous meetings with then-Transportation Secretary Norman Mineta. All the associations got involved—the AOPA, General Aviation Manufacturers Association, and National Air Transportation Association, among them. Olcott shared an anecdote where the leaders were all sworn to secrecy of the contents of those meetings, and then-NATA chief Jim Coyne would quip afterward that they just learned everything that was on the news. In seriousness, though, Olcott called Mineta both reasonable and supportive.

“There, there were multiple outreaches up and down the government chain, outreach to Jane Garvey, who was the FAA administrator at the time, outreach actually to Steve Brown, who was the head of air traffic [for FAA] at the time [now NBAA COO]…there was a substantial amount of communication,” Carr said.

Damato said this is where she really learned to advocate. She would get questions such as if a company has a call sign then they are similar to a Part 121? Or a fractional has a call sign then they are okay? She differentiated between the various operations, that a fractional was not like a large Part 121 charter and what the difference was with Part 135. One point of emphasis was that on corporate aircraft, all passengers were known.

Carr added: “Some of the initial conversations that Jo was having are really insightful, not necessarily just about the technical aspects of what was being asked, but the fact that there was no frame of reference for what they were asking about. They really didn't know about us. This just highlighted pretty brightly that there wasn't a lot of awareness up and down the chain within the government at the time of what general aviation or business aviation was, what it's capable of doing, how it operates—all the things that lead to the policies that are being developed, associated with how we moved forward.”

This factored in as the airspace gradually freed up in chunks, beginning around Class B airspace where large airlines hosted hubs and eventually to Class C, D, and finally small airports “That took us a few weeks to go through,” Carr said. General aviation was permitted to fly IFR flights beginning on September 14 and VFR followed gradually beginning on September 19.

Long-term Restrictions

But a number of restrictions lingered, and some are still in place. It wasn’t until February of 2002 that a Special Federal Aviation Regulation was issued that permitted limited operations to the so-called “D.C. Three” airports. But strict security protocols remain.

And, business aviation flights were not permitted to fly into DCA until 2005, when the DASSP was established. That took years of negotiations and a number of false hopes. Mary Miller, v-p of government and industry affairs for Signature Aviation, which runs the sole FBO at DCA, told AIN at the time that the company would believe it was making progress. “But then we got a phone call saying, ‘you are not opening,’” Miller said.

Finally, the DASSP protocol rolled out with requirements for vetting of the pilots, passengers, baggage, and itineraries—and an approved armed security officer (ASO). NATA’s Coyne was aboard that first flight in, a Hawker 1000 operated by New World Jet for Jet Aviation on Oct. 18, 2005. It was the only such flight that year.

DASSP has remained in place but for years there has been a push to alter the ASO requirement to make DCA a more practical option. DCA became a priority issue not only for Signature but for the industry, particularly because of the airport’s importance in its location next to the nation’s capital.

Security Part of Bizav DNA

Olcott stressed the need to explain that security is part of the DNA of business aviation. “We argued that security was nothing new in business aviation. We argued that the idea of security was integral to business aviation. It was industrial security.“

Carr added that the industry was able to ward off initial attempts of potential draconian measures through this advocacy. “The places that people started for discussions about security would have been devastating if that's where they ended,” he said. “It really was insightful to go through those discussions because we saw them come up repeatedly.”

As an example, he pointed to the Twelve-Five security program that imposed new and built on existing security protocols for charter involving aircraft weighing 12,500 pounds or more. “That was going to be a program that started at 6,000 pounds—so a pretty small airplane,” he said, adding: “We saw the need to engage pretty heavily directly and frequently on how do we keep a very unfortunate incident with scheduled airlines from affecting what we do. That was, and still is, a continuing effort because what we do doesn't always look like what people are used to seeing when it comes to aviation security.”

Carr agreed with Olcott that security was a key part of business aviation. “There's none of this randomness or unknown unknowns associated with our missions, and communicating that to folks was a difficult task for us.”

A New Agency

This effort had slowed as TSA was stood up. While many moved over from the FAA, there was still a learning curve. That also was more difficult because there were major issues, such as security checks throughout airports for all airports, that TSA had to tackle.

“And the early days of TSA from my recollection,” Carr added, “was somewhat of a revolving door. A lot of people came in and out. Everybody we could reach we got in front of to talk about business aviation. We wanted them to know about us. We were very comfortable with FAA, but this was a new agency that was going to have a substantial impact on the success of our future.”

Over the years the business and general aviation community has forged a number of good relationships with TSA officials and particularly through the government-industry TSA Aviation Security Advisory Committee, but the advocacy and education process continues.

“Twenty years on, [TSA} has developed the capacity to do really good things that benefit lots of people. They are really good at screening. They are really good at helping airlines succeed. But I think we have an opportunity to leverage what’s been learned in business and general aviation,” he said.

This becomes particularly important as new modes of transportation emerge, Carr added, pointing to advanced air mobility security. “Who at TSA will play a role in that? I don’t know.”

These efforts continue beyond the TSA. “We can't do anything with a TFR without the Secret Service,” he said, underscoring the need to work closely with such agencies. “I think having a good understanding of their requirements helps us understand why they do certain things.”

He pointed to efforts to open up more gateways to Palm Beach International during presidential TFRs while former President Donald Trump visited the areas.

Customs and Border Protection has become another key agency, and Carr praised efforts made to help ease certain processes, such as online reporting. Now, there’s a Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency within DHS that the industry needs to be aware of as well.

Approaching Security Issues

All of these efforts have shaped the community’s approach to security issues. “I think 20 years ago, we have maybe somewhat of a naive approach that people obviously knew who we were, thinking, ‘We're an airplane-based industry. Of course, people know who we are and what we do.’” Now, Carr said, “The changes that were required and the work that we do really is how to approach a situation. We must validate what they know before we go much further.

The past 20 years have shown, he added, “that you'll get a lot farther if you go in with an eye towards education and not just starting right out on the ground floor and trying to fix a problem. You'll end up getting to where you need to be a lot more quickly. And hopefully with the outcome that you're hoping.”

Another evolution over the past 20 years is the grassroots engagement from the community. “Security has been a pathway towards additional engagement,” Carr said, adding that he believes the downturn of 2008 and 2009 further galvanized that approach. “Twenty years ago, NBAA was absolutely comfortable with being the voice, the sole voice, for business aviation on so many of these issues, because there was an avoidance of the public light. Companies just didn't want the public to know they had airplanes. But today I think we've demonstrated the value of being engaged, having your voice counted.”

This change has become evident and particularly important throughout the pandemic, Damato added. With the association’s business aviation management committee, she said, “There are 20 or 30 flight department leaders saying, ‘Oh, try this, or we're going to try that now, or this is how we're doing.” This approach has spread throughout the community.

Not only who advocates but how they advocate is changing, Olcott added. “We as a community had focused on justification. Justification to me seemed almost offensive. You advocate for something you believe in, you advocate something that has benefit to society, a benefit to people. Those arguments came in very handy when we were trying to keep general aviation from being grounded after 9/11.”

He too stressed the need for continued advocacy. “I think we have to sing the praises of business aviation in a realistic way because I think business aviation has great value.”

Perhaps one of the biggest takeaways from 9/11 for Olcott was preparedness, even for the unimaginable. “Plan to have resources in place before you need them. Because once you have a challenge, it is too late to develop resources. We could not have developed the Command Center presence unless we had previously looked at the problem.”

Twenty years ago when the 9/11 attacks devastated the world's economy and plunged the aviation industry into turmoil, NBAA staffers joined together to help tackle the unprecedented challenges faced by the business aviation industry, both in the immediate aftermath and for the longer term.

Jo Damato

In July 2001, Jo Damato, now the senior v-p of education, training, and workforce for NBAA, had joined the association from Executive Jet Management to fill a newly created role: staffing a general aviation desk at the FAA Command Center.

That desk was years in the making, first proposed in 1998 at a peak time of airline delays. Government officials thought it might be a good idea to have a voice from the business aviation sector as well. Damato described those first few months as “quietly drinking from a fire hose,” trying to get up to speed on the inner workings of the nation’s air traffic control system. Yet people at the center weren’t up to speed on business aviation either.

“Nobody was engaging with me and I was still learning how to engage with people, especially at such a mature facility with seasoned air traffic control professionals.” The managers at the desk held by the then-Air Transport Association (ATA), now Airlines for America (A4A), took Damato under their wing and helped her establish her presence at the facility.

By the time September 11 rolled around that year, they were swapping coffee runs. That morning, there was a “commotion” at the Northeast desk. “I didn’t know what it was, but I knew we’d better hold off on our coffee.”

The staff was following a flight that they thought had likely been hijacked. “I don't want to minimize this, but it played out as something very interesting is happening right now, but not something terrifying,” she said. But then everyone in the room realized that there may be more than one thing happening, particularly since there was no contact with the pilots.

“It got quiet and everybody was on alert very quickly…and then a gasp from the floor. It was clear that an airplane had made contact with the [World Trade Center],” she said. Initially, “no one was thinking anything more than this is a horrible tragedy and what could have happened on an airplane that created something like that.” When the second airplane went in, she said, “I was 20 feet maybe from the man who was in charge of the floor that day. And he said, ‘Shut it down…nothing in or out.’ And very quickly [the national airspace system] was shut off.”

Incidentally, the national operations manager who made that call, Ben Sliney, a veteran air traffic controller but on his first day as manager of the center, described that morning during a forum held by the University of Texas at Dallas and aired by C-Span. After the second aircraft hit the tower, which he saw on screens inside the center airing CNN, they knew, “This wasn’t the usual hijack by some deranged individual, but that this was a concerted attack by a group of people and America was under attack.”

Jack Olcott

Then-NBAA president Jack Olcott had arrived early into the offices on the corner of 18th and M Street on the morning of 9/11. Olcott said he usually tried to get in early to avoid the traffic gnarl that occurs during rush hour in Washington, D. C. The day appeared to be typical until he received a call from NBAA’s head of the government affairs office, Pete West, and was told: “Turn on your TV. An airplane just hit the World Trade Center.”

Olcott said his first thought was some general aviation airplane had deviated off course from down the Hudson River and hit the 110-story building. “And my thoughts were all like others. That's a shame; It's a tragedy. And I suspect, there'll be a lot of finger-pointing about general aviation.” He turned on the television and saw the plumes of smoke coming out of one of the towers. “While I was watching, another airplane, obviously an airliner, hit the remaining tower. It was clear that this was no random accident. This was something quite significant. After that event, things unfolded very rapidly.”

Doug Carr

During this time Doug Carr, now senior v-p of safety, security, sustainability, and international operations for NBAA, had received a call from the office alerting him that a small aircraft had hit the World Trade Center.

Carr headed into the office while running through in his mind a response to this aircraft crash. He knew that even with a small airplane, it would be front-page news. “I'm thinking what's the weather looking like and where did they leave from? I'm trying to put together the pieces in my head about that and things I know we're going to be asked about.”

He took the George Washington Parkway to head towards the office, and “I'm driving by the Pentagon and the third airplane goes in and the fireball, and all of that happens.” Drivers on the opposite side of the road came to a complete stop. “Nobody knew what to do seeing what just happened.” But Carr knew that the situation was grave and journeyed into the office where the team assembled to put the pieces together.

THE AFTERMATH

The moment had reverberated throughout NBAA, as it did the entire aviation industry and the nation. And, it reshaped security from the government’s standpoint. At the time there was no Department of Homeland Security. Nor was a Transportation Security Administration. The FAA handled aviation security in-house.

Since then, the business and general aviation industry has seen security protocols evolve over the years and lasting requirements implemented. These include the Twelve-Five Standard Security Program for air charters, the Alien Flight Student Program for international flight training candidates training inside the U.S., and the increased use of no-fly zones and temporary (sometimes permanent) flight restrictions with “gateway airports.”

Business aviation still can’t fly into Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport without an armed security officer aboard, an approved DCA Access Standard Security Program, and vetting through a gateway. A Special Flight Rules area outer circle and Flight Restricted Zone inner circle capturing the “Maryland 3” airports (Hyde Field, Potomac Airfield, and College Park Airfield) remain in place. So too do ongoing restrictions over Disney parks, sporting events, and certain areas where the President travels.

But looking back, Olcott said having the resources in place to mobilize quickly was critical for not only NBAA but the industry at large, enabling them to weather through the turmoil of the time and its aftermath. And the measures that are still in place now are a far cry from some of the proposals and initial restrictions put in place in the immediate aftermath.

INFORMATION CHAIN

Damato said immediately after the attacks, ATC personnel turned to her and the ATA manager and told them to start talking to their members, make sure they knew who is on their airplanes, and if they haven’t gotten into the air, don’t.

She called NBAA headquarters and coordinated with her immediate manager Bob Lamond, now retired but who was director of air traffic at the time. Lamond headed right to the Command Center and worked with Damato through the time.

She realized since NBAA had a presence at the Command Center, they were considered essential personnel and allowed to stay. “I think that if we had not finally staffed that position, I'm not even sure we would've gotten into the facility now.”

At headquarters, NBAA staff turned the board room into a command center and brought in phones and hooked up screens. Calls poured in, asking how NBAA could get their flight in the air. “We were getting calls literally from movie stars and their flight operations saying, ‘Hey, I've, got a really important thing in Europe. I need to leave tonight.’”

Along with having a spot at the Command Center, another factor worked in NBAA’s favor: it had recently launched a website. Olcott estimated that the website had only been fully live for about six weeks or so before then.

“Back then,” Carr recalled, “websites didn’t have the functionality they do today. They were very text-based.” To reduce the burden on the services, NBAA stripped out all of the graphics and turned it into a continual update got members. Lamond and Damato would call in information and Jason Wolf, who is senior director of information architecture for NBAA and headed up the newly established website at the time, would then post the details.

“Our website became a critical piece of communication capability for us,” Carr said. “We sent everything we could to the website. We probably would not have been nearly as effective if we didn't have the website and the ability to turn it into this massive repeater for the information that we knew.”

In the years since, that website and others throughout the industry have become a critical conduit for the industry, particularly throughout the pandemic.

BUSINESS AVIATION: THE BIG UNKNOWN

At the same time, though, the aftermath shed light on how little people outside of the industry knew about business and general aviation.

On the positive side, despite the initial grounding in the aftermath, business aviation was still able to step up on a limited basis. “We became useful,” Damato said, noting the association was getting a number of questions about what business aircraft could do. Business aircraft were called in to fly in special footpads for search dogs, to help with telecommunications companies that had just lost infrastructure, and to fly blood to where it was needed, among other missions. “There were a whole bunch of unique one-offs that business aviation was able to satisfy because we have resources," Carr said.

Once Command Center officials learned more about NBAA and business aviation, then the questions came: “Can you explain [Part] 91 to us? Can you explain 135 to us?” Damato said, information ultimately taken into consideration as the notams were being developed for operations in the aftermath.

BUSINESS AVIATION AS THE THREAT

“There were various study groups within government saying, well, we can't let business aviation fly because we really don't know what's in the airplanes. Then there was a thought that we can't let charter up. Why? Because the bad guy may charter a plane,” Olcott said. “So, there were a lot of thought groups, finding reasons why everything except the airlines and the military should be grounded.”

The Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), in a retrospective it wrote for the 10-year anniversary of 9/11, noted efforts to restore general aviation flight began immediately after the attacks. “Two days after the FAA grounding, limited airline service was restored, and soon after that, the Bush administration announced that the ‘U.S. aviation system has been restored.’ But general aviation was still grounded, and, in horror, we realized GA was taking the brunt of the fear the attacks had engendered. Were small airplanes now the terror of the skies?” AOPA had asked in an article written by Julie Summers Walker.

Olcott said the general aviation community coalesced to “fight the good fight” with numerous meetings with then-Transportation Secretary Norman Mineta. All the associations got involved—the AOPA, General Aviation Manufacturers Association, and National Air Transportation Association, among them.

“There, there were multiple outreaches up and down the government chain, ….There was a substantial amount of communication,” Carr said.

Damato said this is where she really learned to advocate, explaining the industry.

Carr added: “Some of the initial conversations that Jo was having are really insightful. They really didn't know about us. This just highlighted pretty brightly that there wasn't a lot of awareness up and down the chain within the government at the time of what general aviation or business aviation was, what it's capable of doing, how it operates—all the things that lead to the policies that are being developed.”

This factored in as the airspace gradually freed up in chunks. “That took us a few weeks to go through,” Carr said. General aviation was permitted to fly IFR flights beginning on September 14 and VFR followed gradually beginning on September 19.

LONG-TERM RESTRICTIONS

But a number of restrictions lingered, and some are still in place. It wasn’t until February 2002 that a Special Federal Aviation Regulation was issued that permitted limited operations to the so-called “D.C. Three” airports.

And, business aviation flights were not permitted to fly into DCA until 2005, when the DASSP was established. That took years of negotiations. The DASSP protocol rolled out with requirements for vetting of the pilots, passengers, baggage, and itineraries—and an approved armed security officer. NATA’s Coyne was aboard that first flight in, a Hawker 1000 operated by New World Jet for Jet Aviation on Oct. 18, 2005.

SECURITY PART OF BIZAV DNA

Olcott stressed the need to explain that security is part of the DNA of business aviation. “We argued that security was nothing new in business aviation. We argued that the idea of security was integral to business aviation. It was industrial security.“

Carr added that the industry was able to ward off initial attempts of potential draconian measures through this advocacy. “The places that people started for discussions about security would have been devastating if that's where they ended,” he said.

As an example, he pointed to the Twelve-Five security program that imposed new and built on existing security protocols for charter involving aircraft weighing 12,500 pounds or more. “That was going to be a program that started at 6,000 pounds—so a pretty small airplane,” he said, adding: “We saw the need to engage pretty heavily directly and frequently. That was, and still is, a continuing effort because what we do doesn't always look like what people are used to seeing when it comes to aviation security.”

Approaching Security Issues

All of these efforts have shaped the community’s approach to security issues. “I think 20 years ago, we have maybe somewhat of a naive approach that people obviously knew who we were.” Now, Carr said, “The changes that were required…is how to approach a situation. We must validate what they know before we go much further.

The past 20 years have shown, he added, “that you'll get a lot farther if you go in with an eye towards education and not just starting right out on the ground floor and trying to fix a problem.”

Another evolution over the past 20 years is the grassroots engagement from the community. “Security has been a pathway towards additional engagement,” Carr said. “Twenty years ago, NBAA was absolutely comfortable with being the voice, the sole voice, for business aviation on so many of these issues, because there was an avoidance of the public light. But today I think we've demonstrated the value of being engaged, having your voice counted.”

Not only who advocates but how they advocate is changing, Olcott added. “We as a community had focused on justification. Justification to me seemed almost offensive. You advocate for something you believe in, you advocate something that has benefit to society, a benefit to people. Those arguments came in very handy when we were trying to keep general aviation from being grounded after 9/11.”

Perhaps one of the biggest takeaways from 9/11 for Olcott was preparedness, even for the unimaginable. “Plan to have resources in place before you need them. Because once you have a challenge, it is too late to develop resources. We could not have developed the Command Center presence unless we had previously looked at the problem.”