Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 408503

Safety has long been business aviation’s holy grail, but today that priority encompasses a growing range of risk issues while also becoming entwined with the community’s expanding security component. The threats are real.

On the ground, publicly available real-time flight tracking data provides aircraft ownership details and “actionable information that could be used by anyone with any kind of intent, be that good, bad, or otherwise,” creating identifiable security risks, said Doug Carr, NBAA's senior v-p of safety, security, sustainability, and international operations.

As connectivity enters the cabin, “The cybersecurity threat increases, and the attacks are getting more and more sophisticated,” said Josh Wheeler, senior director of client services at Satcom Direct. He added that as bandwidth increases, “The risk profile just gets greater.”

Concurrently, healthcare issues have also morphed into security concerns. “A medical event in a high-risk location could very quickly turn into a security issue or vice versa,” said John Cauthen, security director of aviation and maritime at medical and security services consultancy MedAire.

All this in a threat environment where simply observing traditional safety standards impels some owners and operators today to outfit their business aircraft with anti-missile defense systems.

Meeting the security challenge properly is a complex, multidisciplinary imperative, tailored to the risks an organization or individual faces. It’s not a “set it and forget it” endeavor, say security experts, but an evolving approach—just as threats evolve—and must be periodically tested. Fortunately, a wealth of resources, solutions, best practices protocols, and other security assistance is available to help counter these largely invisible, but identifiable threats.

The Privacy Security Link

A right and expectation of privacy have long been a bedrock of business aviation’s operating principles, whether to shield confidential corporate activities; protect individuals from potential physical dangers, or a simple desire for anonymity. The FAA aircraft registry complicates privacy rights right by making the identity of U.S.-registered aircraft owners public through an easily accessible resource and potential security vulnerability that is unique.

“A public registry of aircraft in other parts of the world just does not exist,” said Carr.

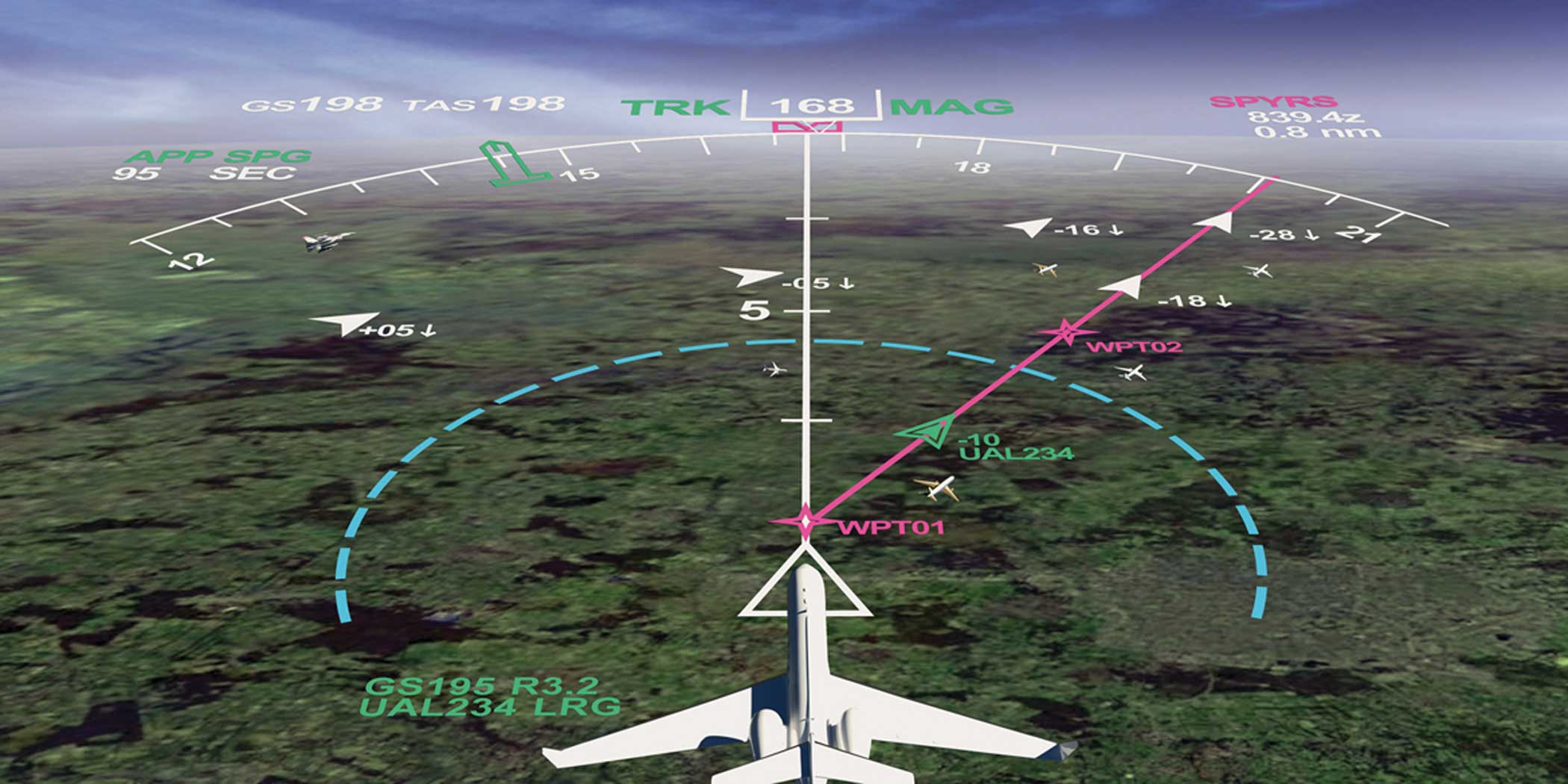

When airborne, the identifying information is transmitted by ADS-B out transponders and dutifully displayed by the FAA for internal use and shared with subscribers—flight tracking services and others—who also disseminate and display the data, allowing anyone to quickly identify the owner and track their flights.

This is in contrast to automobiles—an oft-cited comparison—whose owners can’t be identified by simply looking up a car’s license plate on a phone app or be tracked in its travels around the neighborhood or across the country. Thus, aircraft ownership entities are often structured behind a trust or shell corporation to obscure the owner’s identity.

Business aviation’s privacy concerns came into greater focus when the FAA, early in the last decade, tried to shutter the Block Aircraft Registry Request (BARR) program, which shielded real-time flight tracking identification information of enrolled aircraft from public disclosure. Security consultants testified at congressional hearings on the risks presented by unblocking the data, and the FAA ultimately retained BARR until it was replaced in 2020.

Two FAA programs today allow owners to block or limit the tracking identification information: the Limited Aircraft Data Displayed (LADD) program and Privacy ICAO Address (PIA) program. Security experts recommend enrolling in both.

LADD and PIA

LADD is the successor to the BARR program, enhanced for the ADS-B era, and implemented on Jan. 1, 2020, in conjunction with the deadline for ADS-B-out transponder equipage. Aircraft enrolled in BARR were automatically transitioned into LADD. New applicants can request LADD online or via e-mail or postal mail. The application is simple and straightforward.

Under LADD, third-party vendors that subscribe to FAA feeds (such as flight-tracking networks and services providers such as MROs or management companies) must block the public display of any aircraft registration or call sign that is participating in the program and ensure they do not publicly display historical data of those aircraft.

Enrollees can select vendors authorized to receive their information, though this functionality is still in development.

When airborne, the aircraft’s type, altitude, airspeed, and flight plan information will appear on flight-tracking displays of blocked vendors but call signs or tail numbers will be absent.

But today, other entities outside of the FAA-authorized vendors—ranging from privately owned networks to aircraft tracking enthusiasts—also can obtain ADS-B transmission information directly from aircraft, complete with their identifying data. The LADD program doesn’t block these trackers from gathering or disseminating the information.

The PIA program is designed to plug the gap by providing operators with a temporary Mode S transponder identification—a non-published, six-digit ICAO hex code — that replaces the aircraft registry information from the FAA’s Civil Aviation Registry that would otherwise be attached to an aircraft’s transponder signal. When airborne, an anonymous flight ID number—which operators must also secure for the program—will appear on flight tracking displays in lieu of the aircraft’s tail number.

But applying for and maintaining PIA coverage is more complex and time-consuming than LADD enrollment. The FAA has established a 60-day baseline for processing new ICAO hex code under PIA, a relatively long time to not be flying under the radar if security is a concern. Those already in the program who believe their code has been compromised can apply for an expedited replacement, which currently takes about 20 days.

“Events over the last few months have really highlighted the critical time element when your information has been compromised,” said Heidi Williams, NBAA's director of air traffic services and infrastructure. She cited news coverage of the movements of business jets believed to be owned by celebrities.

Plans call for a third-party vendor to assume administration of the PIA program this year, which is expected to speed up the current processing time.

Additionally, the aircraft’s PIA code will also have to be renewed and changed on an ongoing basis, and each code change is considered a maintenance item, requiring a logbook entry, a flight validation, and other compliance work. And PIA applies only to FAA-controlled domestic airspace; flights operating along oceanic routes, even near the U.S. coast and in the Gulf of Mexico, are not shielded at this time, though the FAA is working with ICAO in an effort to expand the PIA coverage area. Like LADD, PIA is still in development.

But even when fully operational, PIA or LADD cannot ensure anonymity, especially in today’s connected world.

“We’ve had onlookers at the airport who shared all of the goings-on of an operation via social media,” said Williams, regarding the source of some recent accounts of celebrity business jets. “That allowed [trackers] to link those operations with a call sign or a tail number, even though [the aircraft owners] had gone through LADD and PIA.”

Nor are U.S.-registered aircraft the only ones exposed to private surveilling. “Most aircraft flying across the globe today are equipped with ADS-B, and are sharing the same kind of information and subject to greater analysis,” noted Carr.

A Twitter account dedicated to tracking—and flight shaming—jets believed owned by European moguls was said to have played a role in encouraging French government officials in August to call for a ban on business jet flights in the country.

It’s worth noting that many gawker reports on the flight habits of the rich and famous appear to be under the misapprehension that the aircraft’s owner is onboard every flight. Also, what are likely short repositioning legs in the course of charter operations are incorrectly viewed as crosstown jaunts by owners trying to save a few minutes on the freeway.

There’s an important privacy corollary to this misunderstanding: charter customers, though they book flights under their own names, have little chance of being identified as onboard a particular flight, whether ownership of the aircraft is public or not, security experts say. Fractional aircraft owners also have this protection, as they rarely fly on the aircraft in which they are registered as owning a share, these experts further note.

No technological fixes or encryption solutions to the aircraft identification issue appear imminent; ADS-B and avionics systems have no on-off switch that would preclude their transmitting identifying data. Potential workarounds under discussion include an international PIA-type program covering the U.S., Canada, and Eurocontrol.

“About 40 percent of global air traffic flies between those three chunks of airspace,” noted Carr. Domestically, cutting the link that ties certain ICAO Mode S data to a specific aircraft in the FAA registry—a regulatory solution—could also help, according to NBAA.

Secure Connectivity

In the air as on the ground, the internet provides access to a variety of malefactors, and in the connected aircraft, the cabin is typically the focus of attacks. “That’s the biggest point of entry, and the most easily compromised,” said Satcom Direct's Wheeler. “The cyber threat is huge, and it’s never going to slow down.”

Most attacks “cast a very wide net, going after low hanging fruit, in hopes of finding a diamond in the rough,” said Wheeler, trying to capture passwords, usernames, and email addresses, “with the goal of compromising the account or to sell the information.”

Onboard connectivity systems themselves are often unprotected and may be publicly accessible when on the ground. “No one changes the passwords for the sake of convenience, no one locks down their Wi-Fi,” said Wheeler. “It’s mind-boggling to me that you will have c-level executives that may have trade secrets or proprietary information [accessible], and yet they don’t put a Wi-Fi password on it.”

Experts recommend updating passwords regularly and keeping firmware on devices and routers updated; their upgrades often include fixes for security vulnerabilities. Said Wheeler, “Some things you can easily accomplish are going to exponentially increase your security [protection] profile.”

Satcom Direct can view the devices and apps accessing its routers on customers’ aircraft. “We get visibility to the specific port protocol that they’re trying to exploit,” Wheeler said, and a significant number are compromised. “We’re seeing a lot of malware and a lot of different virus activity.”

Onboard routers themselves can be a vector for spreading this malware, even in the absence of connectivity, said Wheeler. “It’s not the norm, but [the malware] can propagate [onboard] from one device, and it doesn’t necessarily require internet access to do it.”

Moreover, while the vast majority of attacks are untargeted, Satcom Direct has seen state-sponsored, advanced persistent threats (APTs) targeting “specific assets” or devices believed connected to an entity or individual.

Major connectivity providers have robust security features built into their services and hardware, and can usually tailor additional security features to meet higher demands. In addition to threat monitoring, Satcom Direct can, for example, encrypt, anonymize, and secure inbound and outbound data through its private network “and on top of that, interrogate for malicious content and events,” Wheeler said.

Air-to-ground connectivity provider Gogo manages and operates its own network through multiple data centers for redundancy and provides Tier 1 and Tier 2 network security monitoring and analysis from its network operations center. All network communication is secured by routing through a licensed spectrum using proprietary link encapsulation, and Gogo’s onboard routers and Avance connectivity systems include built-in system intrusion security.

Viasat handles highly sensitive data for the U.S. Department of Defense, using Type 1 encryption devices and systems—the U.S. government standard for handling confidential, secret, or top-secret documents. Its network security monitoring combines signature and behavior-based anomaly detection, analyzing more than 2.4 billion events daily in monitoring the threat landscape.

Advised Wheeler, “Ask your ISP, ‘Where are you sending my data? Do you own your own data center infrastructure? What encryption policies do you have?’ And if you can’t get an answer, I’d say that’s terrifying.”

But basic security protection can’t stop phishing scams coming through passengers’ email or scammers from using social engineering tactics—for example, making inquiries appear to come from a trusted source—to try gleaning sensitive information. This makes online behavior another necessary security focus.

Scammers shifted from viruses to phishing schemes during Covid, according to some security professionals, using awareness of the government funds available through the 2020 Cares Act (business aviation companies received more than $640 million from it that year) as bait for scams with links to phony offers of grant money or approvals. Desperation and dreams provided the fuel. “People were looking for financial aid or relief, and it made for some nasty business,” Wheeler said of the resulting scams.

"We cannot determine when a phishing email is sent, however, when or if a link within the email is clicked, we see the request out to the malicious site and block the outbound traffic to that site," he said.

As the persistence and success of such schemes illustrate, smart and cautious online behavior—or on any medium—is important in reducing security risks.

“Does your company have a policy about what employees can or cannot post about work?” asked NATA Compliance Service communications specialist Claudia Culmone in a recent webinar on cyber-attacks. She noted examples of efforts in which scammers tried to gather information about individuals over the phone from corporate flight departments, using information posted on social media accounts to make their inquiries seem legitimate. In a poll, 63 percent of the webinar participants reported their companies have social media policies (25 percent were not sure).

Where Health Meets Security

Meanwhile, real viruses and infections — not the computerized variety — have joined the pantheon of evolving risks.

“Since the pandemic, we’ve seen a much stronger crossover between security and medical [concerns] than ever before,” said Cauthen at MedAire. He cited by example an AOG in an unstable location, where physical safety and personal health could both be jeopardized, complicating and delaying the resolution.

MedAire, a Phoenix-based provider of inflight medical resources for both commercial and business aviation, is a division of International SOS, and both organizations have evolved, now complementing their original medical services with security offerings.

MedAire’s basic medical services include real-time in-flight medical emergency assistance to manage and monitor first aid treatment and arranging for medical assistance to meet the aircraft at the most suitable alternate destination. Security services include flight and airspace risk analysis and aviation travel security briefs.

Concurrently, the scope and definition of medical services are also expanding.

“Post pandemic, operators are interested in their crew members’ personal overall wellbeing, and personal health,” said Richard Gomez, v-p of aviation products and solutions at MedAire. “So medical has been transformed from only physical, to mental health and overall wellbeing, and security is not only about the asset of the aircraft, but the asset of the individual person.”

As part of its growth in this area, MedAire partnered this year with security services specialist Bond to offer a personal security monitoring service. Intended for use on the ground in situations where clients feel uncomfortable or unsafe but that are not yet emergencies — the so-called “too early/too late” security problem — the service provides instant contact with a personal security agent who can monitor events and summon additional assistance if needed.

Also pursuant to its holistic healthcare approach, MedAire recently introduced an enhanced client portal, and added client-facing staff for its “human-centric operations.” The strategy is to address three “legs” as MedAire calls them — a team, technology, and partnerships — to provide a sound model for an organization’s security program.

The team approach starts internally by ensuring the flight department communicates with all other company security entities. “Engage on a regular basis as you build new crew policies and flight manuals, and get buy-in from corporate” noted Cauthen. However, he acknowledged that flight operations can be “a bit of a learning curve and an education piece for corporate security professionals.”

Wheeler recommends flight departments and operators conduct recurring security audits and training, and “provide a conduit where [team members] can learn more about realistic, tangible threats, versus this abstract concept of cyber security.”

A host of organizations, NBAA included, offer guidance on business aviation security best practices, including checklists for minimizing risks within flight departments, onboard, cybersecurity procedures, and during aircraft servicing.

Technology provides conduits for learning and keeping team members abreast of evolving threats and countermeasures. But it also offers risk mitigations and solutions, including those capable of meeting risks beyond APTs.

Defensive Armament

Meanwhile, another aspect of security defenses involves those who are in danger of physical harm. Directed IR Countermeasures (DIRCOMs) are designed to protect aircraft from heat-seeking ground-to-air missiles (also called MANPADS). They integrate a thermal camera, mirror turret, and advanced fiber laser technology able to detect, target, and neutralize these threats. Elbit Systems’ Music (Multi Spectral Infrared Countermeasures) family of DIRCOMs can be installed on large-cabin business jets and transport category aircraft including ACJs and BBJs (J-Music); and helicopters and turboprops (Mini-Music), though these installations are most common in military aircraft.

The systems are lightweight, compact, and easily installed on a broad range of aircraft, in both single and multi-turret configurations, according to the Israeli company, and can be integrated with various Missile Warning Systems. Completion centers have confirmed having installed such systems on aircraft.

The Security Picture Ahead

The security cat and mouse, or Whac-A-Mole game, keeps heating up. Technologies like 5G and the evolving Internet of Things have reportedly led to increased cyber-attacks against critical infrastructure coming from a wider range of perpetrators. Are these threats mirrored on the evolving connected aircraft?

“We have to think outside the box,” said Wheeler. “Anything that accesses the internet is susceptible to risk. It’s naïve to think that a system is impenetrable.”

But, Wheeler and others note, international regulatory authorities and standards organizations “are very cognizant of the next generation” of avionics and communications systems in development, and are establishing design requirements aimed at securing and hardening them.

Agreed MedAire’s Gomez, who serves on the Air Charter Safety Foundation’s Board of Governors, “There’s an overall heightened awareness and focus on security, and cybersecurity — the industry is looking at all the right things.”

The air traffic control system itself — perhaps the most integral player in U.S. aviation safety and security — is getting hardened as a result of security demands.

“We are looking at cyber events 24/7, and have resources dedicated to identifying events that could potentially be cyber-related—anything perceived as a system failure, or a service issue,” said Luci Holemans, FAA ATO cybersecurity group manager in June at the Connected Aviation Intelligence Summit in Virginia.

The FAA is adopting a Zero Trust architecture to shield its systems from cyber-attacks. Zero Trust philosophy, a driver of the next generation of digital validation tools, assumes networks are compromised and focuses on defending application data.

The upgrade effort began under a Department of Transportation program in 2020 but became government-wide policy under a 2021 Executive Order aimed at strengthening government computer systems and networks. The FAA infrastructure will also have to accommodate cloud technologies embedded in the ecosystem, and forthcoming unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) and commercial space operations.

A couple of parting thoughts for non-professionals struggling to wrap their organizations around the amorphous concept of security:

“Knowing the solution in place today may not be 100 percent foolproof is as valuable for operators to know as thinking they’re protected,” said Carr.

And though security and compliance protocols can be perplexing and confusing, “You can’t just throw up your hands and say, ‘That’s not my job,’” said Wheeler. “It’s everyone’s job.”

Finally, advised Gomez: “The mantra is to be prepared for the next event. Because there will be a next event, whatever that might be.”

Business aviation’s privacy concerns have come into greater focus with recent social media attention on celebrity use of private aviation.

Two FAA programs today allow owners to block or limit the tracking of aircraft identification information: the Limited Aircraft Data Displayed (LADD) program and Privacy ICAO Address (PIA) program. Security experts recommend enrolling in both.

LADD is the successor to the Block Aircraft Registry Request (BARR) program, enhanced for the ADS-B era, and implemented on Jan. 1, 2020, in conjunction with the deadline for ADS-B-out transponder equipage.

Under LADD, third-party vendors that subscribe to FAA feeds—such as flight-tracking networks and services providers such as MROs or management companies—must block the public display of any aircraft registration or call sign that is participating in the program and ensure they do not publicly display historical data of those aircraft.

Enrollees can select vendors authorized to receive their information, though this functionality is still in development.

When airborne, the aircraft’s type, altitude, airspeed, and flight plan information will appear on flight tracking displays of blocked vendors but call signs or tail numbers will be absent.

But today, other entities outside of the FAA-authorized vendors—ranging from privately owned networks to tracking enthusiasts—also can obtain ADS-B transmission information directly from aircraft, complete with their identifying data. The LADD program doesn’t block these trackers from gathering or disseminating the information.

Meanwhile, the PIA program is designed to plug the gap by providing operators with a temporary Mode S transponder identification—a non-published, six-digit ICAO hex code — that replaces the aircraft registry information from the FAA aircraft registry that would otherwise be attached to an aircraft’s transponder signal. When airborne, an anonymous flight ID number—which operators must also secure for the program—will appear on flight tracking displays in lieu of the aircraft’s tail number.

But applying for and maintaining PIA coverage is more complex and time-consuming than LADD enrollment. The FAA has established a 60-day baseline for processing new ICAO hex code under PIA, a relatively long time to not be flying under the radar if security is a concern. Those already in the program who believe their code has been compromised can apply for an expedited replacement, which currently takes about 20 days.

“Events over the last few months have really highlighted the critical time element when your information has been compromised,” said Heidi Williams, NBAA's director of air traffic services and infrastructure, citing news coverage of the movements of putative celebrity-owned business jets.

Plans call for a third-party vendor to assume administration of the program this year, which is expected to speed up the current processing time.

Additionally, the aircraft’s PIA code will also have to be renewed and changed on an ongoing basis, and each code change is considered a maintenance item, requiring a logbook entry, flight validation, and other compliance work. And PIA applies only to FAA-controlled domestic airspace; flights operating along oceanic routes, even near the U.S. coast and in the Gulf of Mexico, are not shielded at this time, though the FAA is working with ICAO in an effort to expand the PIA coverage area. Like LADD, PIA is still in development.

But even when fully operational, PIA or LADD cannot ensure anonymity, especially in today’s connected world.

“We’ve had onlookers at the airport who shared all of the goings-on of an operation via social media,” said Williams, regarding the source of some recent accounts of celebrity business jets. “That allowed [trackers] to link those operations with a call sign or a tail number, even though [the aircraft owners] had gone through LADD and PIA.”

Nor are U.S.-registered aircraft the only ones exposed to private surveilling. “Most aircraft flying across the globe today are equipped with ADS-B, and are sharing the same kind of information and subject to greater analysis,” noted Doug Carr, NBAA's senior v-p of safety, security, sustainability, and international operations.

A Twitter account dedicated to tracking—and flight shaming—jets believed owned by European moguls was said to have played a role in encouraging French government officials in August to call for a ban on business jet flights in the country.

It’s worth noting that many gawker reports on the flight habits of the rich and famous appear to be under the misapprehension that the aircraft’s owner is onboard every flight. In this vein, what are likely short repositioning legs in the course of charter operations are viewed incorrectly as crosstown jaunts by owners trying to save a few minutes on the freeway.

There’s an important privacy corollary to this misunderstanding: charter customers, though they book flights under their own names, have little chance of being identified as onboard a particular flight, whether ownership of the aircraft is public or not, security experts say. Fractional aircraft owners also have this same protection, as they rarely—and possibly never—fly on the aircraft in which they are registered as owning a share, these experts further noted.

No technological fixes or encryption solutions to the aircraft identification issue appear imminent. ADS-B and avionics systems have no on-off switch that would preclude their transmitting identifying data.

Potential workarounds under discussion include an international PIA-type program covering the U.S., Canada, and Eurocontrol. “About 40 percent of global air traffic flies between those three chunks of airspace,” said Carr. Domestically, cutting the link that ties certain ICAO Mode S data to a specific aircraft in the FAA registry—a regulatory solution—could also help, according to NBAA.