Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 410036

On New Year’s Day, 1914, when the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line launched the world’s first scheduled, commercial airline service to connect the two Florida cities, few among even the most optimistic observers present would likely have envisaged a day when around 600 passengers could travel over 8,000 nm on a double-decked Airbus A380 jumbo liner. The 23-mile hop across Tampa Bay—at barely five feet above the waves—was certainly a “one small step, one giant leap” moment, albeit the service in the Benoist Type XIV aircraft lasted less than five months, providing, for a $5 one-way fare, a 23-minute alternative to a two-hour boat voyage or a drive that could take as long as 20 hours.

In something of a “back to the future” ironic twist, the St Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line’s 109-year-old business model was fundamentally quite similar to the new air taxi services now promised by the 21st-century transportation revolutionaries working to use eVTOL aircraft for so-called urban air mobility (UAM) services. Early applications of all-electric vehicles, typically carrying just two to four passengers, largely consist of short flights of between 20 and 100 miles intended to bypass congested roads within large cities, and in some cases support slightly longer sub-regional services.

We’ll spare the blushes of some of the eVTOL pioneers by recalling the names of those who promised to start commercial flights in 2023, i.e. around now. This baseline projection then got quietly pushed into 2024 and then, in recent months, into 2025.

Electric Dreamers Press For Early AAM Impact

So what’s fuelling what is now commonly referred to as an advanced air mobility (AAM) revolution? The short answer is money and lots of it. A more complete answer is a mix of distributed electric propulsion and increasing automation of flight on a trajectory towards autonomous operations that will not involve a pilot being on board the aircraft.

Multiple companies, many of them start-ups with origins outside the aviation industry, are looking to exploit the new technology to achieve a fundamental, epoch-defining shift in how people and things move around and support previously unthinkable business models. The imperative to reduce aviation’s environmental footprint is also a big motivator, especially in Europe where social consensus is increasingly demanding more from the industry and demanding carbon-reduction goals are being set in the chase for so-called net zero over the next couple of decades.

There is now little doubt that a version of AAM or UAM will happen, with the only questions being when exactly it will become a reality and whether it will achieve sufficient commercial scale and momentum to make a lasting impact. In fact, the technological progress being fermented is also feeding into a wider transformation of air transport, following a continuum that Airbus believes could lead to 200-seat hydrogen-powered airliners flying 2,000 nm by around 2035.

So, perhaps a better question is what’s holding AAM back? Again, the short answer is money, with the availability of new capital seemingly tightening after the boom of 2021. The more complete answer includes the limitations of current battery technology, regulatory complexity, and the need to develop extensive new infrastructure to support what AAM proponents refer to as their ecosystem.

Nonetheless, a small pack of eVTOL frontrunners now have revenue-generating flights in their sights for 2025. Joby, which started working on its plans in 2010, has been flying a full-scale four-passenger prototype for some time. In December, the FAA closed a comment period on the airworthiness criteria it intends to use for type certification of the aircraft, which is similar in architecture to other models that have embarked on the approval process.

In November, another Silicon Valley-based start-up Archer unveiled the four-passenger Midnight aircraft that it too aims to certify at the end of 2024. It is already flight testing the two-seat Maker technology demonstrator and says that Midnight will take to the air in 2023.

In Europe, Germany’s Lilium aims to secure EASA-type certification for its seven-passenger Lilium Jet in 2025. This will have a range of around 155 miles, and the company is already flight-testing a sub-scale technology demonstrator with plans to start flying a production-conforming prototype in 2024.

Another German start-up called Volocopter is working to start services with its two-seat VoloCity model from 2024 in locations including Paris, Rome, Singapore, and Saudi Arabia. This will be limited to flights of little more than 20 miles, but the company is also working on a four-seat model called the VoloConnect that will have around three times that range. It is also preparing to offer a freight-carrying model called the VoloDrone.

The UK’s Vertical Aerospace appears to be on a similar trajectory, having recently started hover flights with its VX-4 prototype. Like the Lilium Jet, this four-passenger model is expected to have a similar range of more than 150 miles and be used to connect cities that don’t currently have air service, and also to feed passengers into airports.

Autonomy Or Bust

All of these eVTOL aircraft will enter service with a single pilot on board, although Volocopter intends to transition to autonomous operations as soon as regulations permit. But some companies insist that autonomous flight is the only way to make AAM business models succeed, even if that means not being among the first market entrants. Neither the FAA, nor Europe’s EASA, has even hinted at a timeline in which they expect to be ready to permit passenger-carrying autonomous flights, albeit progress is being made in the use of drones for applications such as surveillance and light cargo deliveries.

In China, EHang insists it is close to getting type certification for its EH216 Autonomous Aerial Vehicle from the country’s CAAC air safety regulator, and also clearance to operate fully autonomous flights for applications such as air taxis and sightseeing. It is not clear to many Western observers on what basis the CAAC is ready to give the go-ahead to full autonomy.

EHang is involved in all aspects of developing the required ecosystem. In the city of Guangzhou, it is establishing a command-and-control facility to act as the nerve center for autonomous operations as well as a “5G Intelligent Air Mobility Experience Center” that includes a vertiport, battery recharging equipment, and a maintenance set-up.

Wisk Aero, backed by Boeing and Google co-founder Larry Page’s now-closed Kitty Hawk eVTOL developer, is adamant that autonomous operations are the only way to go. In October 2022, the company unveiled what it says is its sixth-generation aircraft, a four-passenger model intended to fly up to around 90 miles without a pilot on board.

The company knows it won’t be first-to-market in the eVTOL gold rush, and it doesn’t care, taking the view that it will be ready for the quantum leap into autonomous operations when regulators are ready to offer an approval path to this stage. Wisk has already logged more than 1,600 autonomous flight test hours in its two-seat Cora technology demonstrator, at test sites in both New Zealand and California.

Hybrid-Electric Advocates Say Get Real

But not everyone is content to make do with the current limits of battery technology, which for now is capped at around 450 WH/kg in terms of energy density. For them, hybrid-electric propulsion is a far more pragmatic stepping stone, holding open the prospect of significantly greater payload and range than the all-electric crowd.

Other incentives are said to be a more straightforward path to certification with less technology risk, and also a lot of scope for converting existing aircraft to the new means of propulsion. Additionally, hybrid aircraft will be able to operate from existing airports without having to wait for battery rechargers to be widely available.

As counter-intuitive as it might seem, the late 20th-century vintage Cessna Grand Caravan (albeit still in production today) stands to be one of the first aircraft to undergo conversion to a hybrid powertrain. Several companies have their sights set on this versatile, utilitarian airframe, with Ampaire having achieved the first flight with its Eco Caravan refit in November.

By combining a compression ignition engine in Ampaire’s integrated parallel configuration with battery packs electric motors, the Eco Caravan could have a maximum range as long as 1,000 miles. In most commercial use cases, however, it will likely fly multiple shorter distances each day, whether carrying up to nine passengers or cargo.

Ampaire co-founder and CEO Kevin Noertker, sees a clear path to scaling up hybrid-electric propulsion in aviation. Next in his sights is a conversion of the 19-seat DHC-6 Twin Otter (to become the Eco Otter), and he expects to see 30- to 50-seat regional airliners entering service in the 2030s.

“We’re taking a crawl, walk, run approach and that’s why we’re starting with [conversions of] an existing fleet of aircraft, and will then work with OEMs to make the propulsion system standard on new-build aircraft,” Noertker told AIN. “When we get 10, 20, and 30 years from now, there will be multiple [electric-powered] clean sheet airplanes.”

Also seeking a more direct path to market while making the most of available technology is Electra, with its hybrid-electric short takeoff and landing (STOL) aircraft. The Virginia-based company is tapping blown-lift aerodynamics to develop a fixed-wing model that it says will carry nine passengers or 1,800 pounds of cargo, and be able to operate from sites such as heliports with no more than around 300 feet available.

In Scandinavia, where both the Norwegian and Swedish governments are pushing for the early phasing out of domestic flights depending on fossil fuels, Heart Aerospace has plans for a 30-seat regional airliner called the ES-30. The September 2022 announcement marked a change in strategy prompted by Air Canada and other prospective launch customers to boost payload and range by abandoning an earlier plan for a 19-seat all-electric model called the ES-19. The switch will cost the Swedish company two years, with certification and entry into commercial service now projected for 2028.

Chasing the Hydrogen Holy Grail

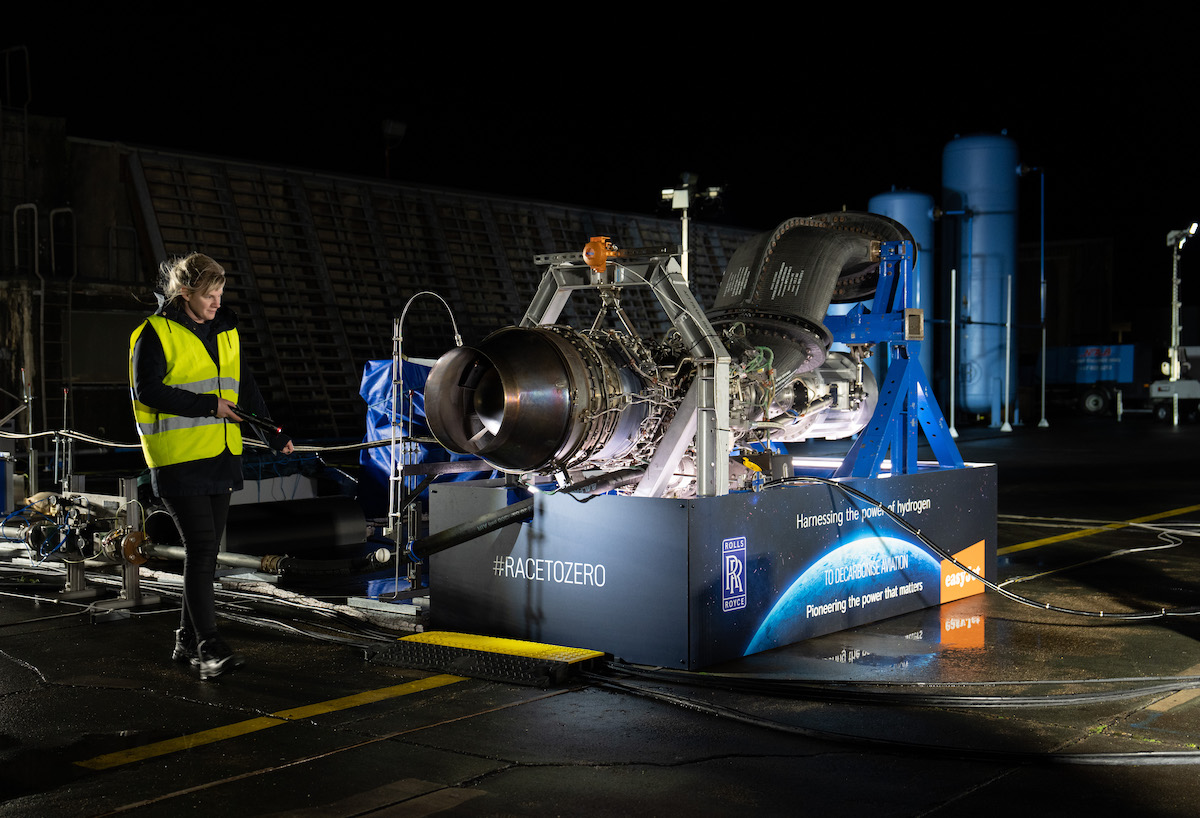

But for some AAM trailblazers, hydrogen power is the true holy grail. Ground testing of both direct combustion and fuel cell-based systems is underway, but new fuel poses significant challenges in terms of storage and distribution.

Companies including ZeroAvia and Universal Hydrogen are preparing to integrate their fuel-cell-based powertrains into existing regional airliners like the de Havilland Dash 8 and the ATR 42, with ambitions to bring 40- to 80-seat aircraft to market by 2027. ZeroAvia is starting with the conversion of the 19-seat Dornier 228 twin turboprop and says this could be ready to operate the world’s first hydrogen-powered scheduled airline services as early as 2024.

The switch to hydrogen, which its advocates maintain is the true green fuel, is dependent on an extensive rollout of fuel supplies at airports. The pioneers are making their own efforts to jump-start the expansion of this critical ecosystem, which they hope will be faster than the rollout of sustainable aviation fuel, but it seems clear that only the buy-in of oil industry giants will result in sufficient momentum worldwide. Shell last year made a commitment that could prove to be a breakthrough.

By contrast with its rival Boeing, Airbus is foremost among the hydrogen evangelists. When it announced its Zero E project in September 2020, Airbus said it expected to be ready to choose from three possible airframe concepts by 2025, leading to a full program launch in 2027 and entry into service in 2035. The European aerospace group is also working on an eVTOL design called the CityAirbus NextGen.

One of many fascinating aspects of covering the space-race vibe of this new wave of aviation technology and business models is the culture clash between aerospace behemoths like Airbus and the upstart advocates of a new Year Zero for the industry in which old assumptions sometimes seem to be cast aside for dramatic effect.

In recent years the capital-hungry have made some very aggressive pledges to prospective backers about achieving an unprecedently rapid market entry with radically new aircraft and a fast-track to commercial returns. Several of these pioneers are now somewhat discretely eating humble pie, having had to tactfully push back certification timelines in the face of regulatory realities.

In a further sign of realism getting a grip, the past 12 months or so have seen a rapprochement between the upstarts and aerospace royalty, with industry leaders like Rolls-Royce, Honeywell, Collins, and GKN taking key roles in several of the more promising new aircraft programs. At the same time, the door remains open for aviation to learn some critical new tricks from the automotive industry, which has plenty to teach it about the mass production that will be required if AAM ever fulfills its promise to scale up at a pace the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line’s founders would have found dizzying.

While the energy created by the new wave of aviation’s over-caffeinated hyperbolists has surely provided a welcome shot in the arm for an industry demoralized by the fallout from the Covid pandemic, the fact remains that the course of aerospace progress is still measured in decades. The 2020s remain on course to be the decade that sees distributed electric propulsion reshape short-haul transportation, and, perhaps optimistically, this should be followed by more momentum moving into the 2030s.

What remains to be seen in the wider picture as the world moves towards the 2050 net zero mandate agreed by the United Nations COP climate change conferences is the extent to which various regulatory carrots and sticks might be used to turn air transport increasingly green. In this regard, the 2040s seem more likely to be crunch time, and the impact of this change by then may be largely determined by the success, or otherwise, of market-led initiatives.