Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 413201

There is a saying in the aviation business that if you’ve seen one airport…you’ve seen one airport. There may be truth in that axiom, but not when you’re talking about a shortage of hangar space among the top 200 or so airports frequented by business aviation passengers. The problem is not new to the industry, but it has become more acute over time for multiple reasons, the first being simply that large markets tend to attract large amounts of business aircraft.

“The problem is people want to be in Los Angeles, Teterboro, Miami, DFW—they want to be in specific places,” said Milo Zonka, vice president of real estate with Florida-based FBO operator and hangar developer Sheltair. “Florida, in general, is definitely constrained—everything from Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Naples, Orlando, Tampa, Jacksonville is full. Of course, we’re really talking about those hangars that can accommodate anything. If you are scrounging for a 16- to 18-foot hangar for a light jet, you might be able to find something in a secondary market.”

Another factor is the longevity of business jets. The age of the business jet fleet has increased as aircraft that in the past would have been put out to pasture have gained new value in the post-Covid private aviation boom. “There is so much demand for private jets now that even if you have a 30-year-old jet that otherwise would have been retired, as long as it is safe and airworthy, it makes sense to keep it in service,” said Tal Keinan, CEO of private hangar developer Sky Harbour. “There is also a technology component. Jets get better over time and live longer over time, which speaks to a swelling population.”

While aircraft are lingering longer, the jet population continues to grow as OEMs meet the demand with new aircraft that will also compete for the existing hangar space. Last year saw 712 business jet deliveries worldwide, with the U.S. accounting for nearly 70 percent of the market or more than 400 new aircraft. Sheltair’s Zonka explained the math: “You take 400 airplanes and the average [hangar space needed] between light, mid, and large jets is 5,000 square feet each, you are talking two million square feet of hangars that have to be built just to accommodate what came off the line,” he said. “Even if you are only talking a million square feet, that is thirty-three 30,000-square-foot hangars, and there are probably only 10 or 15 being built at the moment.” Given current construction prices, Zonka estimates the cost for each at approximately $9 million. “But you are dropping $9 million 30 times just to accommodate this year’s deliveries, and then you have to do it again next year.”

Bigger and Bigger

The aircraft themselves may be the largest factor. “There is a drive toward larger aircraft and larger hangars so that puts pressure on where these aircraft live and go,” said David Best, Jet Aviation’s senior v-p of regional operations for the Americas. “We want to build facilities that are relevant today, but also for the future.”

In 1996, the largest aircraft in Bombardier’s product lineup was the Challenger 604, which has a ground footprint of 4,485 sq ft. That year, the Canadian airframer introduced the Global Express as its new flagship. The long-range business jet more than doubled the 604’s footprint at 9,400 sq ft. “That was only 27 years ago, which in the span of aviation infrastructure isn’t a very long time when you look at 35-year [FBO] leases,” noted Doug Wilson, president and senior partner of industry consultancy FBO Partners. Since that time, Bombardier has delivered more than 800 legacy Globals, equating to more than 7.5 million sq ft of hangar space for just that type. It has since delivered at least 100 of the follow-on Global 7500, which is even larger with a footprint of 11,648 sq ft. Gulfstream has seen similar aircraft evolution. In 1996, its GIV-SP took up 6,942 sq ft of hangar space while today’s G650 is more than 3,000 sq ft larger at 10,000 sq ft. Dassault’s under-development Falcon 10X will be even larger at 12,100 sq ft.

Height vs Footprint

But it is not just their footprints that are a concern regarding those aircraft but their heights as well, with the latest ultra-long-range business jets requiring door heights of 28 feet. While that has become a standard these days in the high-traffic areas of the Northeast, Florida, Texas, and California, elsewhere they are still generally the exception.

As Keinan explained, “You’ve got plenty of hangars—especially in the higher-end locations such as the New York area—that have 28-foot-high doors but most of the installed base in the country is 24 feet and down because when these hangars were built 30 to 40 years ago, that would have accommodated the tallest business jets.” He calculates that since 2010, there has been an 81 percent increase in the square footage of aircraft with a tail height of more than 24 feet for a total of 16.6 million sq ft. “Back in the late 1980s, your ideal hangar might have been 10,000 square feet and it met your GIIIs and GIVs of the day, but today that same hangar is probably at a minimum of 15,000 square feet as an ideal, given the size of the aircraft,” said Curt Castagna, president and CEO of the National Air Transportation Association (NATA) as well as head of hangar developer and operator Aeroplex Group Partners. “Depending on the type of operations you are having, meaning Part 91 vs 135, your ideal hangar might be 30,000 sq ft-plus to accommodate nesting of multiple airplanes.”

He noted that in the Los Angeles area alone, companies have added more than half a million square feet of hangar space over the past several years, all of which is now fully occupied. “I think you can say demand is definitely outstripping supply in the major metropolitan areas, and then in the secondary markets, there might be a little bit of capacity, just not the right capacity, the 28-foot-high doors,” Zonka told AIN. “We’re full in every location and it’s a mad dance in South Florida, for example. It’s a daily search for aircraft that are either new to the owner or the owner is relocating.”

Given that level of demand, one would imagine new hangars would be sprouting like mushrooms. Part of virtually every lease award or renewal is a capital infrastructure requirement by the airport. Multimillion-dollar investments such as hangars are typically made early on in the lease to provide the longest time possible to amortize the costs.

“I think what is important to realize is hangar development goes in cycles with the ground leases and the economy, and so I would say in the late 1980s and early 1990s there were a lot of 30-year leases that went into play for airport developments around the country,” said Castagna. “Now we are coming full circle again 30-something years later where a lot of these developments are coming up to where they are reverting back to airports.”

Those airport sponsors can choose to offer the existing FBOs a lease renewal, put the property up for a request-for-proposal contest to attract other operators, or simply choose to take over the operation itself. “If you think about it in the context of the lease cycle, if an FBO built hangars with a lease that they got in, say, 2000, they’ve already exhausted 22 years on their lease, and there are only another 10 or so years left,” Wilson told AIN. “Are they going to invest in a brand new 28-foot-door hangar when the airport won’t necessarily give them an extension to amortize it?”

Space Available

FBOs are building hangars when they deem it fiscally prudent to do so, but in many cases finding places to put those hangars is a problem. “The whole other problem when you start talking to airports like Teterboro is they don’t have any land left,” said Zonka. “They are running out of dirt.”

That has caused aircraft operators to seek out secondary and possibly tertiary airports in more crowded regions. Clay Lacy Aviation is building an FBO featuring a quartet of 40,000-sq-ft hangars at Connecticut’s Waterbury-Oxford Airport (KOXC). “There’s been a lot of discussion about new hangars being built in White Plains, new hangars being built in Teterboro, and other airports in the surrounding area, but this is really happening,” said David “Buddy” Blackburn, Clay Lacy’s senior v-p for its KOXC FBO operations. “The buildings are going up, so that’s a big deal for the Northeast for sure.”

At those airports where development (or redevelopment) is possible, hangar operators are encountering more headwinds resulting from the Covid-induced changes in the economy. “We finished a hangar in the Los Angeles area in 2018 that between hangar, office, and terminal space was roughly 45,000 square feet, and that hangar was about $7.2 million,” Castagna told AIN. “That hangar around the middle of 2022 might have been around $11 million to $13 million just because of the construction costs—steel and labor and the other pressures on the project—which all go into the metric of evaluating the return on investment and the lease term.”

Those rising costs are indeed playing a role in the decisions to launch construction, according to some companies. “We’ve got half a billion dollars in projects that are on our books right now that we want to turn dirt on,” Zonka said. “[But] they are in markets that can’t support the rent because the construction is so expensive.” Castagna added that because of the increasing costs, the end user is going to bear the burden in markets where the existing rents are so low that it is tough for FBOs to make financially sustainable developments.

Sky Harbour, a hangar complex builder and operator with facilities in Houston and Nashville, recently opened its third location, at Miami Opa-locka Executive Airport. Among the three facilities, it has brought nearly 400,000 sq ft of high-end hangar space online, with a further 300,000 sq ft of aircraft shelter to open by the end of this year in Denver and Phoenix, followed in early 2024 by 170,000 sq ft in the Dallas area. According to CEO Keinan, the company plans to develop millions of square feet of new capacity. It has vertically integrated, manufacturing its own hangar components to speed construction and better control its supply chain, yet it too has been affected by the recent price increases in steel and labor, which have an effect on the rents that are eventually charged as companies seek to make back their investments.

Waiting Time

“Anytime you build a hangar, it never happens overnight,” said Chuck Suma, COO of the Million Air FBO chain. “It’s usually a 12- to 18-month project to get to the point where you put the shovel in the ground, so we’ve had to track costs as we go along and make sure we are constantly updating our pricing structures so we understand what the total cost of the build is.” He added that pricing on construction materials such as steel can vary depending on when the order is placed. “We typically do a fixed firm price for contractors at the time we ink the deal so once we get to the permitting stage then you know exactly what your final costs are.”

“Against the constraints of infrastructure development because of lease terms and obviously the cost, we have seen the market responding with higher per-square-foot rates and a greater focus on the real estate as a function of the FBO business,” said Wilson. “That was thrown into the most contrast during Covid.” On April 13, 2020, business aviation reached its low point, off by 75 percent from its normal activity. “But pretty much every based tenant paid their rent because it’s really hard to get a hangar once you’ve lost your spot,” Wilson added.

Another change wrought by Covid was the desire by high-net-worth people to retreat from crowded urban areas to more rural locations that typically did not see much business aircraft traffic and lacked the infrastructure to accommodate it. “Ten years ago, if you had said ‘Bozeman, Montana,’ we would have said, ‘Where’s that?’” quipped Best. “Now we’re putting a 40,000-sq-ft hangar there and we’ve got strong demand from our customers to be there.”

Million Air’s Suma described it as a change in patterns, where customers are now heading to these vacation destinations earlier than they used to and staying longer as well. “There is still the resort traffic, but a lot of what we are seeing with the large aircraft coming in are the people who own homes there.”

Making the Most of What You’ve Got

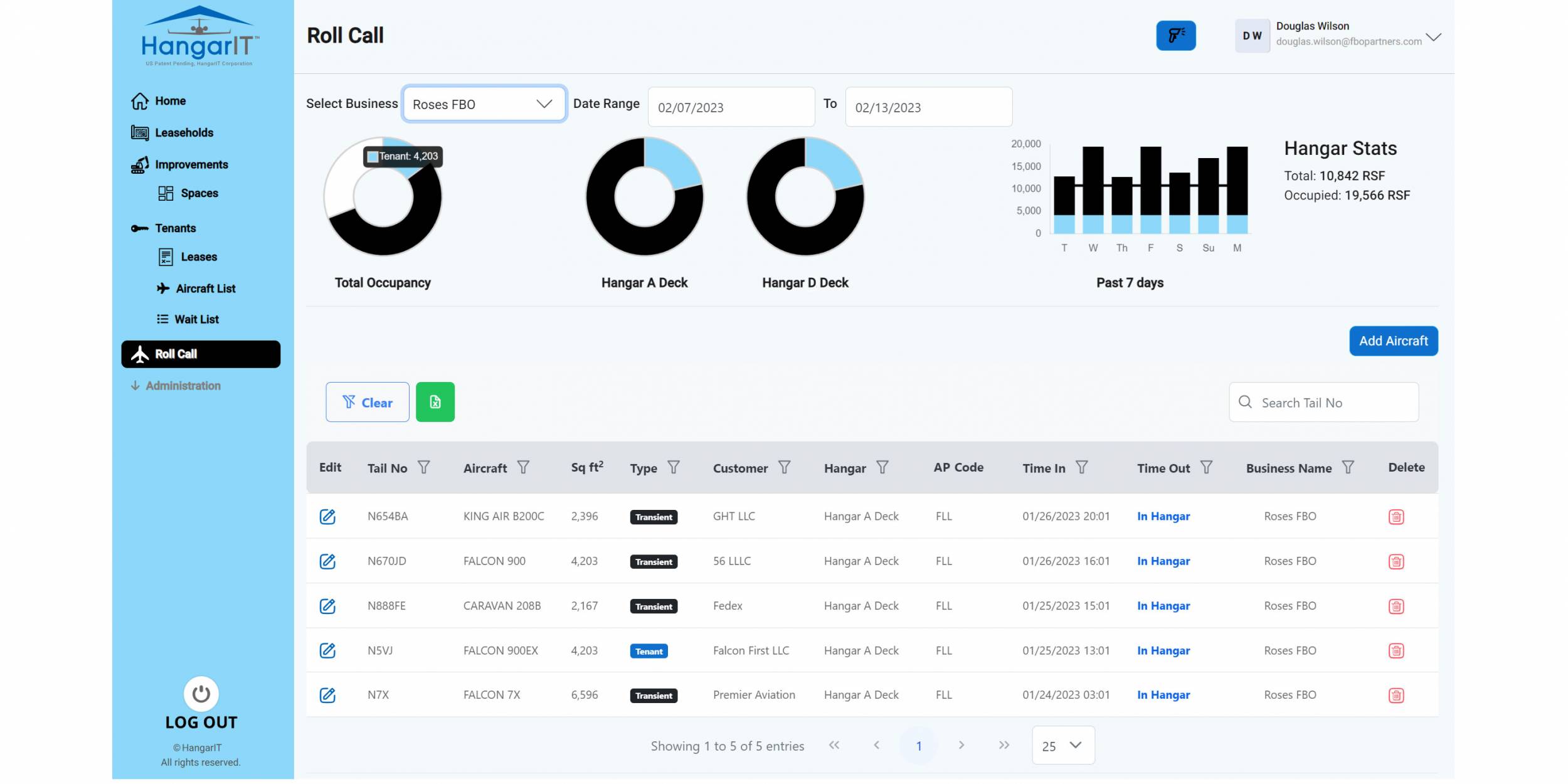

To help give FBOs the best use of their limited hangar resources, FBO Partners has developed Hangar IT, a software program designed to allow hangar keepers to swiftly and accurately determine their hangar space availability at any given moment. At its most basic, the program allows FBOs to enter all their tenant contracts into a database where the system can automatically flag ending leases for renewals and/or pricing adjustments. The system feeds these alerts to the company’s accounting system for further action.

The second function determines the most accurate occupancy in the operator’s hangars. “That is performed by capturing all your existing tenants from your lease documentation,” explained FBO Partners president and managing partner Doug Wilson. “Those tail numbers go into the system, which automatically recognizes the exact aircraft type and assigns the correct square footage to the aircraft.” Through a feature called “Roll Call,” aircraft can be assigned to one of the FBO’s hangars. Each time line service technicians enter that hangar to move an aircraft, they will scan a QR code on the door, which will bring up the hangar roster. They will then enter the tail number of the aircraft they are moving, and the program will automatically deduct the correct amount of space in the hangar and calculate the level of occupancy, thus allowing the FBO to immediately know how much space it can offer to transient aircraft. Wilson noted that the system is in beta testing with an eye toward full release later this year.

A third function, once the patent--pending program gains market acceptance, will be a marketplace where hangar operators can post their vacant space, allowing flight departments to reserve and pay for guaranteed transient hangar space ahead of time rather than simply being placed on a waiting list.