Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 423978

At this year’s Bombardier Safety Standdown, contract pilot Kevin Van Splunder took the stage to share his experience during an extremely hard landing and subsequent fire in a Cessna Citation X+ on August 5 in Jamestown, New York.

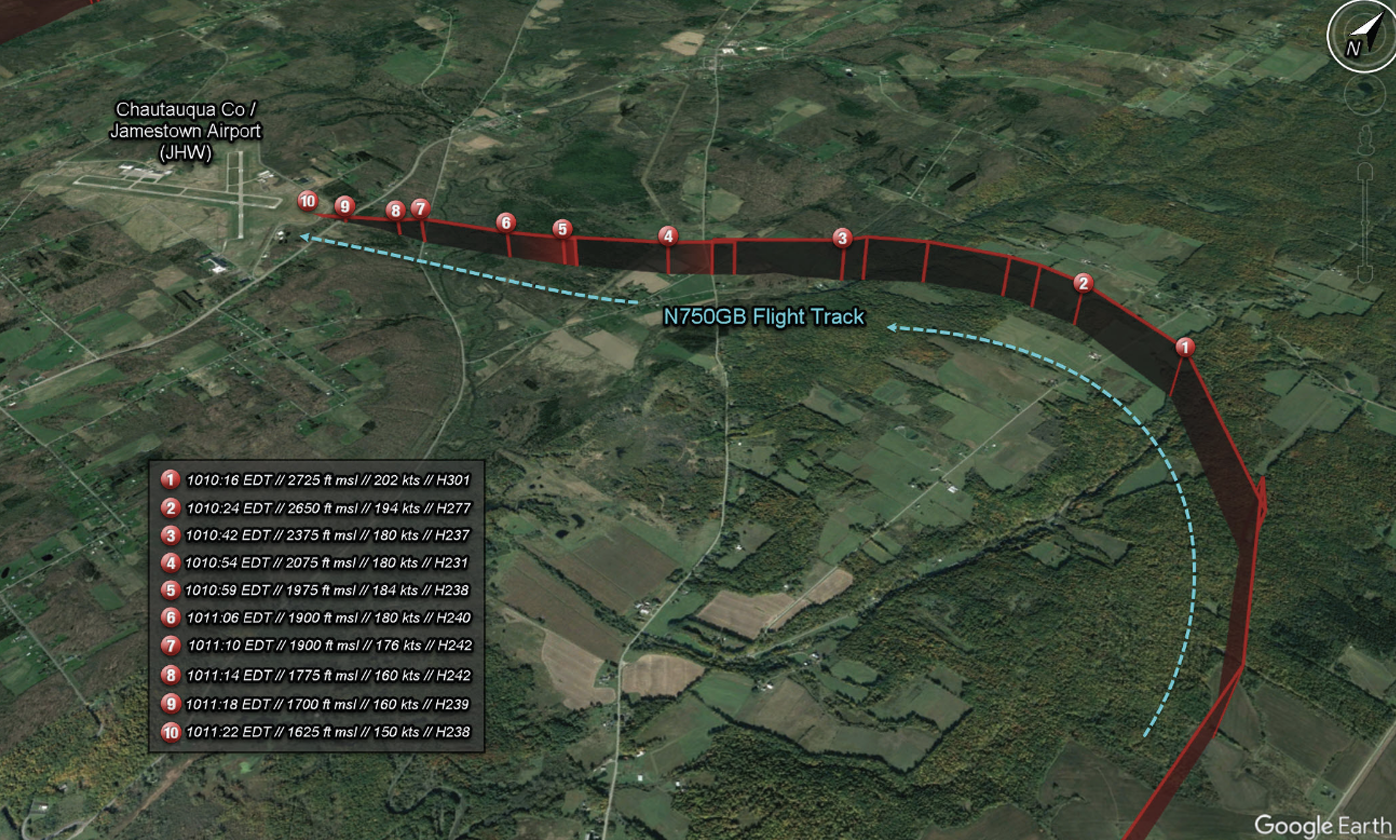

Details about what caused the failures in the airplane aren’t yet available, but Van Splunder shared an image of the flight track of the airplane during its short seven-minute flight. “I've learned, I've applied—and you'll understand why—and now I'm here to share it,” he told the audience.

Climbing through 5,000 feet, he smelled smoke and pointed that out to the captain, who said he didn’t smell the smoke. But Van Splunder commented, “Well, that’s interesting, maybe we should do something.” At 10,000 feet, the jet began to level off and accelerate, and then it started descending, uncommanded. “All of a sudden, we saw ourselves in a descent at 494 knots and 6,700 feet per minute. It's about 73 seconds to impact.”

As a young pilot, he recalled the training he received from “old codgers” who taught him to close his eyes and learn how to touch every switch in the cockpit. “Know what the different switches feel like,” he said. “We don't get that information from CAE and FlightSafety, as much as I think we need it. You need to do that in the aircraft.”

In a previous job as director of operations, Van Splunder brought that training to his fellow pilots. He would have them wear smoke goggles covered by duct tape and put them in a dark cockpit, then simulate an emergency landing. “Go ahead and get out, open up the emergency exit door in your hangar. Have your chief pilots and your safety personnel set up a day that you can get in the plane and you can open up that door and make sure that you can do it without sight.”

Returning to the ill-fated flight, he remembered a strong feeling of confidence that he knew that he would be walking away from the “really bad landing.” At 10,000 feet, he said, “the stabilizer trim ran full nose down to keep us accelerating, and then everything started to fail. The autopilot failed. The primary stab trim failed. I knew the checklist without even having to pull it out. I activated the secondary stab trim, and that also failed.

“Now with all the other CAS [crew alerting system] messages that were on the CAS list, we didn't have any time to pull out checklists and start reading and seeing what the systems were [doing]. It's the knowledge that you learn that you have to apply. What are you going to do? What speed do you have to be at? The only way we could stop our descent was to continue our accelerated speed. Yeah, we maybe broke a law and went faster than 250 knots below 10,000 feet. But trust us, neither one of us cared.”

One of the first captains that Van Splunder flew with “was adamant to always have 121.5 [the emergency frequency] on your second comm [radio],” he said. “That's what saved us. I was able to talk to the air traffic controller. They told us where the airport was because we had smoke in the cockpit. And even though oxygen masks can be worn, you’re not going to see much past that.”

The Citation impacted the ground 200 feet before the runway threshold and bounced into the air, then onto the runway before sliding onto the grass, bouncing back into the air and spinning around, and finally coming to a stop in a total of just 2,020 feet.

“We didn't have much time,” he said, “and if I was in that cabin probably 10 seconds longer, we wouldn't be here. I knew I had to get out. We both agreed I was the first to exit because of my training that I've either taught myself or learned over the years. I knew exactly how many feet, how many steps it was going to take for me to get to the emergency exit door.

“When I passed the main entrance door, it was so engulfed in flames that I couldn't even reach to get the handle. I made it back to the emergency exit door and ripped it out. I can't tell you that I lifted the thing and released the cover and pulled the handle up like they tell you to do nice and easy, because, trust me, you're not thinking nice and easy. I ripped it out of the wall, threw it outside, and then I looked down.

“The wing had separated from the fuselage, and fuel was boiling out like it was lava. I yelled back to the captain and said, ‘We're not going out this way!’ At that point, he came back to me and said, ‘The main door is open.’ I came down like a freight train. I'll tell you, he's a lot bigger than I, and I almost ran straight over the top of him, but we got out of the airplane. I had a few burns and a few cuts. He unfortunately suffered some second-degree burns and some fractured vertebrae. But we're both doing well, and we're both flying.

“But I go back and say that [it’s] because of the training I had from the old people. I can tell you that when I was younger, [I thought] I don't need to know that, it's never going to happen. Well, guess what? It happened, and I'm really glad that I had that training. So I did it because that's how I was taught. And I was able to, without thought, apply that, and with that application of my knowledge, I was able to get out of the aircraft, get the captain out of the aircraft, and we walked away.

“As I said from the beginning, I at no point thought that I wasn't going to make it. I knew I was going to walk away. I just didn't know how long the walk was going to be and from what end of the runway. And that's because we kept our heads calm and cool. We had good communication all the way down, and we did what needed to be done.

“So I take that and give that to you, all that from us who've now been through it,” Van Splunder concluded. “There's not too many people that I know that have been through too many crashes, and I don't ever want to do another one, but I know if it happens, I'll be trained well enough that I can get out and do the same thing I did before.”

Contract pilot Kevin Van Splunder took the Bombardier Safety Standdown stage to share his experience during an extremely hard landing and subsequent fire in a Cessna Citation X+ on August 5 in Jamestown, New York.

Details about what caused the failures in the airplane aren’t yet available, but Van Splunder said of the experience of the short seven-minute flight: “I've learned, I've applied—and you'll understand why—and now I'm here to share it,” he told the audience.

Climbing through 5,000 feet, he smelled smoke and pointed that out to the captain, who said he didn’t smell the smoke. But Van Splunder commented, “Well, that’s interesting, maybe we should do something.”

At 10,000 feet, the jet began to level off and accelerate, and then it started descending, uncommanded. “All of a sudden, we saw ourselves in a descent at 494 knots and 6,700 feet per minute. It's about 73 seconds to impact.”

As a young pilot, he recalled the training he received from “old codgers” who taught him to close his eyes and learn how to touch every switch in the cockpit. “Know what the different switches feel like,” he said. “We don't get that information from CAE and FlightSafety, as much as I think we need it. You need to do that in the aircraft.”

In a previous job as director of operations, Van Splunder brought that training to his fellow pilots. He would have them wear smoke goggles covered by duct tape and put them in a dark cockpit, then simulate an emergency landing. “Go ahead and get out, open up the emergency exit door in your hangar. Have your chief pilots and your safety personnel set up a day that you can get in the plane and you can open up that door and make sure that you can do it without sight.”

Returning to the ill-fated flight, he remembered a strong feeling of confidence that he knew that he would be walking away from the “really bad landing.” At 10,000 feet, he said, “the stabilizer trim ran full nose down to keep us accelerating, and then everything started to fail. The autopilot failed. The primary stab trim failed. I knew the checklist without even having to pull it out. I activated the secondary stab trim, and that also failed.

“Now with all the other CAS [crew alerting system] messages that were on the CAS list, we didn't have any time to pull out checklists and start reading and seeing what the systems were [doing]. It's the knowledge that you learn that you have to apply. What are you going to do? What speed do you have to be at? The only way we could stop our descent was to continue our accelerated speed.”

One of the first captains that Van Splunder flew with “was adamant to always have 121.5 [the emergency frequency] on your second comm [radio],” he said. “That's what saved us. I was able to talk to the air traffic controller. They told us where the airport was because we had smoke in the cockpit. And even though oxygen masks can be worn, you’re not going to see much past that.”

The Citation impacted the ground 200 feet before the runway threshold and bounced into the air, then onto the runway before sliding onto the grass, bouncing back into the air and spinning around, and finally coming to a stop in a total of just 2,020 feet.

“We didn't have much time,” he said, “and if I was in that cabin probably 10 seconds longer, we wouldn't be here. I knew I had to get out. We both agreed I was the first to exit because of my training: I knew exactly how many feet, how many steps it was going to take for me to get to the emergency exit door.

“When I passed the main entrance door, it was so engulfed in flames that I couldn't even reach to get the handle. I made it back to the emergency exit door and ripped it out. I can't tell you that I lifted the thing and released the cover and pulled the handle up like they tell you to do nice and easy, because, trust me, you're not thinking nice and easy. I ripped it out of the wall, threw it outside, and then I looked down.

“The wing had separated from the fuselage, and fuel was boiling out like it was lava. I yelled back to the captain and said, ‘We're not going out this way!’ At that point, he came back to me and said, ‘The main door is open.’ I came down like a freight train. He's a lot bigger than I, and I almost ran straight over the top of him, but we got out of the airplane. I had a few burns and a few cuts. He unfortunately suffered some second-degree burns and some fractured vertebrae. But we're both doing well, and we're both flying.

“But I go back and say that [it’s] because of the training I had from the old people. I can tell you that when I was younger, [I thought] I don't need to know that, it's never going to happen. Well, guess what? It happened. And I was able to, without thought, apply that, and with that application of my knowledge, I was able to get out of the aircraft, get the captain out of the aircraft, and we walked away

“I at no point thought that I wasn't going to make it. I knew I was going to walk away.”