Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 413733

Anyone watching the news around the South China Sea and elsewhere in Asia recognizes the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has intensified its campaign to exert pressure on its island neighbor, the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan.

Besides a constant stream of speeches and declarations regarding Beijing’s intentions to take back the island “by force, if necessary,” the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) and the air arm of the Navy (PLAN) stand as the main instruments of intimidation by the Communist Party of China (CPC). A report issued by the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) in early March projects that PRC armed forces' future activity “could include more Taiwan Strait centerline crossings or missile overflights of Taiwan.”

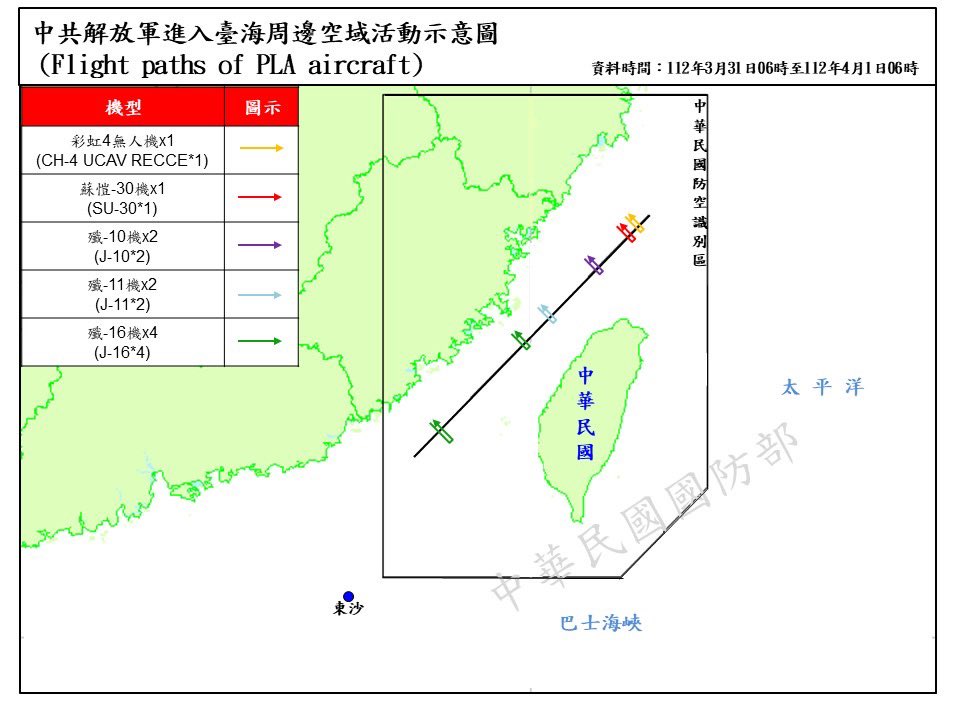

The centerline crossings to which the report refers involve the increasing—both in frequency and number—harassment flights of PLAAF and PLAN aircraft operating near the ROC. The crossing itself refers to when PLAAF aircraft “violate” the median line in the Taiwan Strait, which has served as an unofficial barrier between the PRC mainland and the ROC over which neither side had stepped.

From 1955 to 1999 no PLAAF aircraft had ever crossed the median line. But, beginning in 2019, China began to shunt aside the unofficial “red line” and has since increased operations to the point where today such regular flights have practically erased it altogether.

The number of aircraft involved in the exercises has increased to the degree that in December 2022, 71 PLAAF and PLAN aircraft and drones took part in “show of force” flights, the largest such one-day exercise of its kind to date.

Fighter aircraft types seen crossing over the median line mainly are Chinese-produced models, including the following:

• Shenyang J-11B—The first Chinese-produced fourth-generation fighter aircraft is a reverse-engineered version of the Russian Sukhoi Su-27. An initial purchase of Su-27s sold to the PRC in the early 1990s came after Shenyang Aircraft Works won a contract to license-produce the Su-27 (designated J-11 in PLAAF service). The transfer of production technology then provided the basis for the Chinese to copy the aircraft. Halfway through the contracted 200-aircraft production run for the Su-27SK models, the PRC canceled the remainder of the license-assembly plan. The Shenyang plant now carries the capability of producing its own J-11B models, but the design team officially claims that the aircraft is not an “exact copy” of the Su-27 because “it is only 95 percent of the size of the original Sukhoi aircraft.”

• Shenyang J-16—As with the J-11B, the J-16 is a copy of a Russian design, in this case, the Su-30MK. The PLAAF operates at least 250 of this type, including the J-16D—a jamming platform similar to the Boeing EA-18G Growler.

• Chengdu J-10 – Several variants frequently operate south of the ROC. The J-10 resembles a hybrid of an American Lockheed Martin F-16, the Israel Aircraft Industries (IAI) Lavi technology demonstrator, and some characteristics (particularly the air intake of the earliest J-10 models) taken from the Russian Project 1.42 MFI prototype. A single-engine installation of the Su-27’s AL-31F engine modified for the J-10’s maintenance requirements powers the aircraft.

No Fifth Generation Appearances

Few of the Russian designs from which China developed its fighters have participated in the harassment flights, nor have any of the 24 advanced Su-35s that the PLAAF procured “off-the-shelf” from the Komsomolsk plant in Russia. Chinese advanced and so-called “fifth-generation” designs have almost never taken part in the exercises.

The most famous of the Chinese derivatives—the twin-engine Chengdu J-20—ranks as the largest fighter of its kind and the first stealthy aircraft ever developed by Chinese industry. It is larger than the U.S. Lockheed Martin F-22A and longer than the J-11 and J-16 models. Chinese designers claim that they now produce their own engine to replace the Russian-made AL-31F powerplant for the program.

Last year, at the November 2022 Air Show China, the program’s chief designer, Yang Wei, told the press that two or more new versions of the J-20 are under development, although he did not provide any details. China has manufactured more than 200 J-20s in four separate production batches, compared with the 187 F-22As built in the U.S. before the abbreviation of that aircraft’s production.

A PLAAF pilot identified as Yang Juncheng told state-run Chinese Central Television (CCTV) that “he was able to see the entire island [of Taiwan] from his cockpit.” That would imply that the J-20 not only crossed over the median line but that it entered Taiwanese airspace, which would have meant a violation of sovereignty if detected.

The ROC armed forces have issued no reports of such a breach; if the island’s air defense units could see the J-20 it might have chosen not to say, leaving the Chinese designers unsure of whether the Taiwanese sensor network could detect the aircraft.

Chengdu’s main rival, Shenyang, also has begun flying the final version of the J-35, a twin-engine fighter comparable in size to the U.S. F-35 meant to become the next-generation carrier-capable fighter for the PLAN. A new, higher-thrust engine reportedly has entered series-production now, which would solve the problems that the PLAN have encountered launching fighters from their carrier decks while carrying a full weapons load.

The same memo from the DNI’s office stated that Beijing “is working to meet its goal of fielding a military by 2027 designed to deter U.S. intervention” in the event of any crisis involving the ROC. The same document states that Beijing will also become increasingly aggressive in opposing any increases in U.S. diplomatic and military support to Taiwan. Continuing acceleration of production of such advanced aircraft has alarmed those in the U.S. defense establishment that they account for the airpower component of the long-term plan.

Another War?

In January of this year, U.S. Air Force General Mike Minihan penned a private memo warning his colleagues that they needed to prepare for war with the PRC, which he indicated could start as soon as two years from now. His comments added to the speculation that Beijing’s long-running ambitions to conquer Taiwan have become closer than previously thought.

Minihan now heads the USAF Air Mobility Command and zeroed in on the complications associated with both the ROC and the 2024 general elections in the U.S. The Taiwan balloting could push the island closer to declaring independence, which is anathema for Communist Party leaders in Beijing, raising concerns about Chinese reprisal.

In the U.S., the 2024 election will create the usual confusion of an incoming administration. How to simultaneously continue to support Ukraine in its war against Russia and maintain the long-running military partnership between the U.S. and the ROC will top the list of major defense and foreign policy dilemmas.

“Reuniting” the ROC to become part of the Chinese mainland is a near-obsession for PRC leader Xi Jinping. While previous PRC regimes have talked aggressively about taking back the island, the proposition has assumed new urgency since Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi secured himself a third term in office this past November. Meanwhile, amendments to the national constitution effectively allow him to become another one of the world’s presidents-for-life. Xi has mandated that the PLA be capable of taking Taiwan by 2027, the 100th anniversary of the founding of the force.

“The PLA are upping their game in the Indo-Pacific region to the point where they may actually think that going to war with the U.S. will be too great a temptation to pass up,” said a NATO-nation intelligence officer who spoke with AIN. “The key is whether or not the U.S. can keep up its profile in the region—as well as continue to support Ukraine—and thereby avoid the war Minihan is predicting could come sooner rather than later.”