Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 406119

A helicopter was lost and four people died trying to save a fisherman’s piece of thumb.

The accident investigation that followed was one of the most thorough and painstaking in Irish and perhaps even European aviation. It touched on virtually every aspect of related technology, training, human and survival factors, navigation, operations, and regulation related to helicopter search and rescue (SAR) and spawned 42 separate safety recommendations.

It began on the evening of March 13, 2017. R118, a Sikorsky S-92A being operated as a search and rescue aircraft for the Irish Coast Guard by CHC Ireland (CHCI), was dispatched to a point 140 nm off that country’s Mayo (west) coast at night, in foul weather. The mission: evacuate a crewman from a 260-foot-long fishing vessel who had lost the top part of his thumb in an accident. The shipboard medic had already staunched the bleeding, administered pain killer, and consulted with doctors onshore who advised there was little to be done and in all likelihood the appendage could not be saved. This was not a medical emergency and while there was little medical benefit to be gained, SAR dispatchers launched R118 on its high-risk mission anyway. The wisdom of that decision would be the focus of much scrutiny in the years to come and in the pages of an exhaustive 348-page final accident report released this past November by Ireland’s Air Accident Investigation Unit (AAIU). The AAIU’s 2019 preliminary report triggered a flurry of objections from CHCI to the point that for the first time in its history an AAIU report was subject to reexamination.

In summarizing its own work on the accident, the AAIU noted that its report, “Highlights the importance of robust processes in relation to the following areas: Route Guide design, waypoint positioning, and associated training; reporting and correcting of anomalies in EGPWS [enhanced ground proximity warning system] and charting systems; fatigue risk management systems; Toughbook [portable computer] usage; en route low altitude operation; and the functionality of emergency equipment. It is particularly important that an operator involved in search and rescue has an effective safety management system, which has the potential to improve flight safety by reacting appropriately to safety issues reported, and by proactively reducing risk with the aid of a rigorous risk assessment process. The final report identifies the importance of the levels of expertise within organizations involved in contracting and tasking complex operations such as search and rescue, to ensure that associated risks are understood, that effective oversight of contracted services can be maintained, and that helicopters only launch when absolutely necessary. Finally, regulatory authorities have a role to play in assuring the safety of aviation operations, including search and rescue activities.”

With regard to launching rescue missions only "when absolutely necessary," the report explained that the National Maritime Search and Rescue Framework provides the criteria for decisions about when to launch a rescue, including that "[SAR] comprises the search for and provision of aid to persons who are, or are believed to be, in imminent danger of loss of life." The report added that "properly qualified officers" can use their initiative "in providing a SAR response in circumstances where these procedures are judged to be inappropriate." However, in this case, "officers' actions should conform as closely as possible to those instructions contained in the Framework most closely pertinent to the circumstances and they should keep all other parties involved informed."

On the night of the accident, the Irish Air Force advised they could not provide customary fixed-wing “top cover” for the mission due to personnel availability, so CHCI dispatched a second S-92A, R116, this one from its base across the country in Dublin, to provide that service. R116’s crew already had logged a full day. Aircraft commander Dara Fitzpatrick had returned home from the day's flying and retired for the evening when she got the call to return to base, as had copilot Mark Duffy. Winch operator Paul Ormsby and winchman Ciaran Smith rounded out the crew. Fitzpatrick and her crew originally discussed routing direct to Sligo en route to refuel but later changed that decision to the Blacksod Helicopter Landing Base based on favorable weather reports received en route. Those reports—ceiling 400-500 feet and horizontal visibility of three miles—proved overly optimistic.

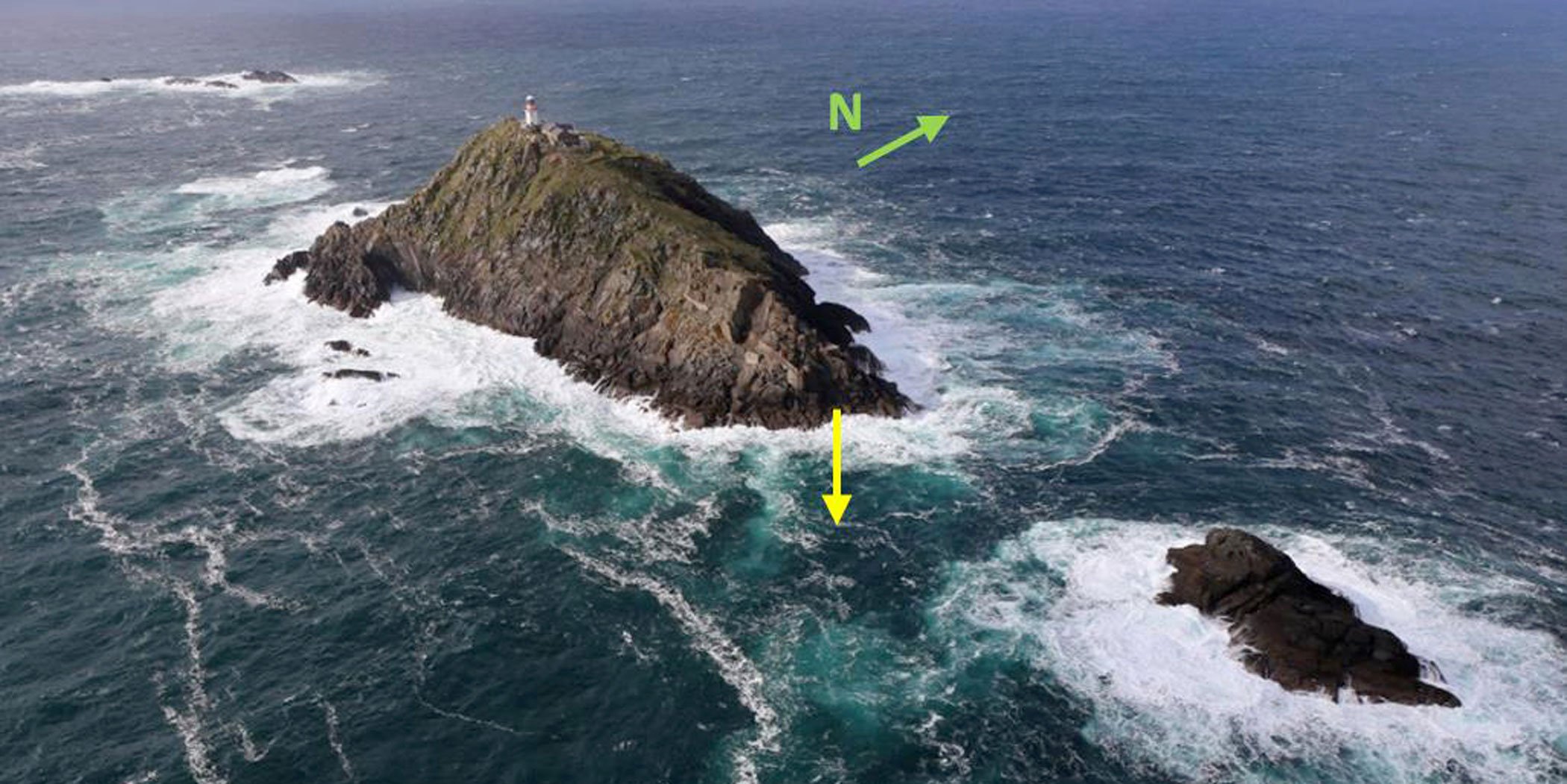

R116 approached Blacksod from the east at 4,000 feet, overflew it, and then began a descent to 200 feet above sea level (ASL) before reversing course to join the approach, which required it to pass abeam Black Rock, an elevated rock cropping 9 nm west of the Blacksod helipad with a lighthouse and helipad at 282 feet ASL, with an elevation of terrain and lighthouse listed at 310 feet ASL in CHCI’s route guide. Outbound, R116 would pass to the north, inbound to the south. In conversation gleaned from the cockpit voice recorder (CVR), Fitzpatrick and Duffy admitted that they had not flown in this area in some time. Fitzpatrick said it had been close to 15 years. Although Black Rock was a known hazard, it was not loaded into the S-92A’s Honeywell EGPWS at the time, even though CHCI flight crews had noted this omission as early as 2013. Crews with more recent local knowledge made a point of crossing Black Rock with plenty of altitude margin, sometimes flying at 900 ASL or higher.

The decision to descend to 200 ASL proved fatal as the crew likely was operating with incomplete information. As the AAIU noted, “The Flight Crew descended the helicopter to 200 feet and used the FMS to manuever ‘Direct To’ the first waypoint, BLKMO, on the APBSS route, unaware that BLKMO was adjacent to a 282-foot obstacle comprised of terrain and a lighthouse.”

Fatigue also could have played a factor. At the time of the accident, aircraft commander Fitzpatrick had been awake for 18 hours and co-pilot Duffy for 17. The report noted, “The tempo of the mission was different to east coast missions and furthermore, the SAR support nature of the mission was known to be monotonous, increasing the risk of the Crew succumbing to fatigue.”

On the inbound course, R116 likely encountered winds from the southwest of up to 40 knots, forward visibility near nil, and a ceiling at or below 200 feet above ground level, based on subsequent weather observations from Blacksod. The wind was blowing R116 into Black Rock. While the beam at the lighthouse there was active, it was likely obscured by clouds. Reflections from the helicopter’s running lights probably added to the problem. There also were issues with the cockpit lighting, altered for night vision installation, although night vision goggles had yet to be provided. The crew routinely brought their own flashlights aboard to compensate. But the diminished lighting, combined with the hard-to-read font, graphics, and color scheme of the company route guide, only added to the stress and confusion. Onboard radar likely was of little value, according to the AAIU. “Radar was operated on the 10 nm range throughout the descent and maneuvering to commence APBSS [the approach]. GMAP2 mode on the weather radar uses the colour magenta to represent terrain returns—the same color as the active track and waypoint on the S-92A navigation display. Black Rock was not identified on radar, which was likely due to obscuration caused by the magenta BLKMO waypoint marker and the magenta track line to the waypoint marker.”

Nor were the charts loaded into the “Toughbook” computer used by the crew. The report found that “The 1:250,000 Aeronautical Chart, Euronav imagery did not extend as far as Black Rock. The 1:50,000 OSI imagery available on the Toughbook did not show Black Rock Lighthouse or terrain and appeared to show open water in the vicinity of Black Rock. The AIS transponder installed on the helicopter was capable of receiving AIS Aids-to-Navigation transmissions; however, the AIS add-on application for the Toughbook mapping software could not display AIS Aids-to-Navigation transmissions.”

It was winchman Paul Ormsby, operating the helicopter’s infrared camera, who saw the danger when the S-92 was a mere 0.3 nm or 600 meters from Black Rock flying at 90 knots. In the final seconds of the flight, he advised the commander to “come right.” It took six seconds for the commander to acknowledge, at which point Ormsby said, “twenty degrees right, yeh.” Fitzpatrick then advised Duffy, “Okay, come right, select heading, select heading.” Duffy acknowledged two seconds later, “Roger, heading selected.” Four seconds later, Ormsby could see that it was too late, imploring the pilots to “Come right now..come right…come right!” Less than one second later synthetic voice “altitude, altitude” warnings sounded in the cockpit as the CVR recorded the sounds of impact.

R116 collided with terrain on the western edge of Black Rock and fell into the sea. The bodies of Ormsby and Smith were never recovered. Duffy was found strapped to his seat in the main wreckage, submerged 40 meters down. Fitzpatrick’s personal locater beacon suggests that she submerged at least 10 meters before coming to the surface, but likely drowned during the ascent. The AAIU found the probable cause of the accident was, “The Helicopter was maneuvering at 200 feet, 9 nm from the intended landing point, at night, in poor weather, while the crew was unaware that a 282-foot obstacle was on the flight path to the initial route waypoint of one of the operator’s pre-programmed FMS routes.” But it also cited a dozen contributory factors, central of which was, “It was not possible for the Flight Crew to accurately assess horizontal visibility at night, under cloud, at 200 feet, 9 nm from shore, over the Atlantic Ocean.”

The loss of R116 comes down to a tired flight crew flying in bad weather, at night, in unfamiliar territory, with incomplete information, on an unnecessary mission.

It was a bad night at Black Rock.