Click Here to View This Page on Production Frontend

Click Here to Export Node Content

Click Here to View Printer-Friendly Version (Raw Backend)

Note: front-end display has links to styled print versions.

Content Node ID: 418970

Perhaps for the purpose of motivating investors, the launch of revenue services with eVTOL aircraft has commonly been characterized as a revolution. But, in the early stages at least, the operational phase of so-called advanced air mobility (AAM) seems likely to be more of an evolutionary process as pioneering service providers seek to meet existing operational requirements.

There seems to be a consensus that greater flexibility and productivity promised from groundbreaking AAM technology—including increased flight automation and eventually full, pilotless autonomy—will have to be realized at a later stage, when aviation safety regulators may be comfortable with more profound changes to operating rules. Initially, at least, early providers of air taxi services seem to accept that they will be treated much like existing commercial charter operators under the FAA’s Part 135 rules and their equivalents in jurisdictions such as Europe.

The General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA) has increasingly served as a forum for advancing discussions about the arrival of eVTOL aircraft in the air transportation sector, and its membership now includes several of the pioneering start-ups in the field. Working with the National Air Transportation Association, the National Business Aviation Association, and the Aircraft Electronics Association, GAMA is creating a document to provide guidance for the new generation of operators, covering topics such as crew training. The International Business Aviation Council is also supporting these efforts with plans for a version of its International Standards for Business Aircraft Operations for the new sector.

The group’s director of global innovation and policy, Christine Dejong, acknowledged that much of the discussion now—less than three years before initial commercial services are expected to begin in 2024—is on the prospect of operators applying for exemptions under the current rules. For instance, she explained to FutureFlight that the use of electric propulsion is likely to require multiple Part 135 exemptions relating to requirements for both pilots and maintenance procedures.

“Recharging [aircraft batteries] is a big factor, including how the necessary permits will be issued for the infrastructure needed on the ground,” Dejong said. “But it is still early enough that there will be time to take account of unique needs like this.” She pointed to research being conducted by the FAA’s Office of Airports to spread knowledge about these needs and support a uniform approach.

According to Lowell Foster, GAMA’s director of global innovation and engineering, early-phase commercial operations will launch with the support of well-established air traffic control procedures and traditional navigation and communication systems. In his view, it is an advantage that new eVTOL aircraft, at least in the U.S., are set to complete type certification under existing, albeit amended, rules because this means they can be covered by established Part 135 operating requirements.

“From a pilot-training perspective, it is anticipated that a lot of people will come from jobs where they have had a lot of experience with commercial operations,” Foster explained. “Using Part 135 has benefits because there isn’t a need to do a full type rating [for each new aircraft], and [instead] you can build training—including any required ‘differences’ requirements—into the operational specifications.”

One aspect of so-called AAM that, for now, distinguishes it from existing fixed-wing and helicopter charter service is that many of the new eVTOL aircraft developers also intend to be the operators and service providers, even though most have no previous experience in this area. Dejong sees this as a positive factor, because “the company [that] knows the vehicle in and out is the same one operating and maintaining it.”

That said, GAMA predicts significant evolution in the operating model over the next five years, with much of this driven by the concept of simplified vehicle operations, which seems to be shorthand for the expectation that fully trained pilots will not necessarily be required. That, say the prospective eVTOL revolutionaries, is imperative if the AAM business model is to scale up to the point where the numbers of aircraft and flights around the world far outstrip current volumes. Very simply, they say, there will not be enough pilots to support this eventuality, and this is what is driving the shift to so-called vehicle operators, whether in the aircraft or on the ground.

“'Simplified vehicle operations' is a very broad term, but it’s allowing the industry to wrap its head around all the anticipated changes,” said Foster. “We’re talking about a simplified pilot interface so that rather than using traditional controls for pitch and yaw, it’s possible to just fly a [preset] flight path.”

In his view, traditional stick-and-rudder pilot skills will still be needed at first, but this need will lessen as navigation systems become more automated. He anticipates the industry reaching a point where the pilot, or vehicle operator, would maybe need only two or three hours of transition training to operate a new aircraft.

Dejong and her colleagues see no prospect for standards being compromised in a rush to reshape commercial aviation. “The authorities are very sensitive to safety issues and it is certainly high on our minds at GAMA,” she told FutureFlight. “For the successful rollout [of new air taxi services], our members know that safety is absolutely paramount.”

The Vertical Flight Society also has been actively involved with the efforts of other trade associations and professional bodies to be a responsible midwife in the birth of commercial eVTOL aircraft operations. According to executive director Mike Hirschberg, the past five or six years have seen significant progress and maturity in the development of standards and regulations that he feels will make this a safe and credible mode of transportation.

"Standards development organizations like ASTM International, EUROCAE, and SAE International have been looking at the hundreds of standards and requirements referenced in certification documents and developing appropriate industry standards to address the unique aspects of electric-powered vertical flight," he explained to FutureFlight.

While not disputing the multiple challenges to the launch of eVTOL operations, Hirschberg is convinced these can be successfully overcome, given the huge investment of time, money and hard work being made by pioneers in the sector.

"AAM missions are some of the most ambitious, yet attainable, operations ever envisaged for transforming society's relationship with aviation," he commented. "No one should be expecting any shortcuts to Part 135 certification."

FutureFlight asked seven acknowledged front runners in the race to start commercial eVTOL operations to explain their plans to launch services. Volocopter and Vertical Aerospace did not respond, but the other five companies provided input as follows:

Archer intends to launch services in 2024, for the most part operating its four-passenger aircraft itself, with the exception of up to 200 that it expects to sell to United Airlines. Founder and co-CEO Brett Adcock confirmed that the company will adopt Part 135 rules to start when services get underway in anticipated launch cities Los Angeles and Miami.

“There will be different phases, and we’re not expecting there to be 100,000 aircraft right away, and we’ll see more of the scaled-up approach from 2028 and beyond,” he commented.

Initially, Archer intends to use existing ground infrastructure, including helipads, as it begins installing vertiports and retrofitting existing facilities.

Adcock confirmed that this will require deep pockets, which Archer now hopes to fill from the proceeds of its planned $1.1 billion IPO-merger with special purpose acquisition company Atlas Crest. He added that United Airlines’ provisional commitment to spend up to $1.5 billion buying aircraft will provide further funding for the manufacturing phase, as well as provide expertise from an established Part 121 airline, with the possibility that Archer’s pilots might be trained by United.

Quizzed about the complexities of launching commercial operations, Adcock indicated that he doesn’t see that as the biggest challenge for the start-up he launched in late 2019. “The hard stuff for me is all the vertically integrated enabling technology, the software, the batteries, and also the high-volume manufacturing,” he said.

Archer believes that the backing it secured in January 2021 from the Stellantis automotive group’s Fiat Chrysler business will be critical in providing the depth of manufacturing experience it needs.

Adcock said that he sees no need to look beyond Part 135 as the basis for Archer’s operating model. At the same time, he remains adamant that as the eVTOL aircraft’s manufacturer, his company—despite its lack of any past pedigree in air transport—remains best placed to make a success of commercial operations.

“At the end of the day, the best company in this space will be the one that builds and operates aircraft,” he concluded. “When you break up [that model] you lose the incentives and control that are needed for the product to keep getting better. Plus, operations can be very lucrative, with high cash flows that will be three times more valuable than selling aircraft.”

By contrast, Embraer, which has decades of experience manufacturing airliners, business jets, and military aircraft, has yet to set a date for its eVTOL aircraft entering service; nor has it stated on what basis the aircraft will be operated or by what companies. Andre Stein, who leads the Brazilian manufacturer’s new Eve Urban Air Mobility Solutions division, said that it intends to serve a mix of customers, including companies that would operate its aircraft. “We won’t necessarily operate the aircraft ourselves, but we see great opportunities to find the right local partners, with which we will create [transportation] solutions that would cover a comprehensive package of services,” he explained.

As it works to advance the design of its eVTOL aircraft using a simulator and various early-technology demonstrator models and ground-test units, the Eve team is already focusing hard on operational requirements. Like others in the field, it is eager to stress the need to develop the wider ecosystem to support the anticipated mobility services.

This approach has prompted Embraer to partner with companies such as air traffic management specialist Airservices Australia and ground infrastructure provider Skyports. It has also become involved with a planned "sandbox" trial for urban air mobility in London and is building on the experience of its sister company Atech, which supports air traffic services for high-volume helicopter movements in and around the Brazilian city of Sao Paulo.

“We do see these vehicles as being easier to fly than helicopters, which are more complex,” Stein told FutureFlight. The flight deck in Embraer’s eVTOL will incorporate its fifth generation of fly-by-wire technology and the airframer has already evaluated a simplified man-machine interface in the flight simulator.

For now, Embraer sees existing Part 135 rules, with some adaptations, as the safe basis for launching operations, while holding out the prospect that future technology could support regulatory change. In its view, pilot training could be one of the biggest areas of change, as autonomous operations gather momentum, supported by enabling technologies including augmented reality to develop the new generation of pilots needed to support the anticipated high volume of operations.

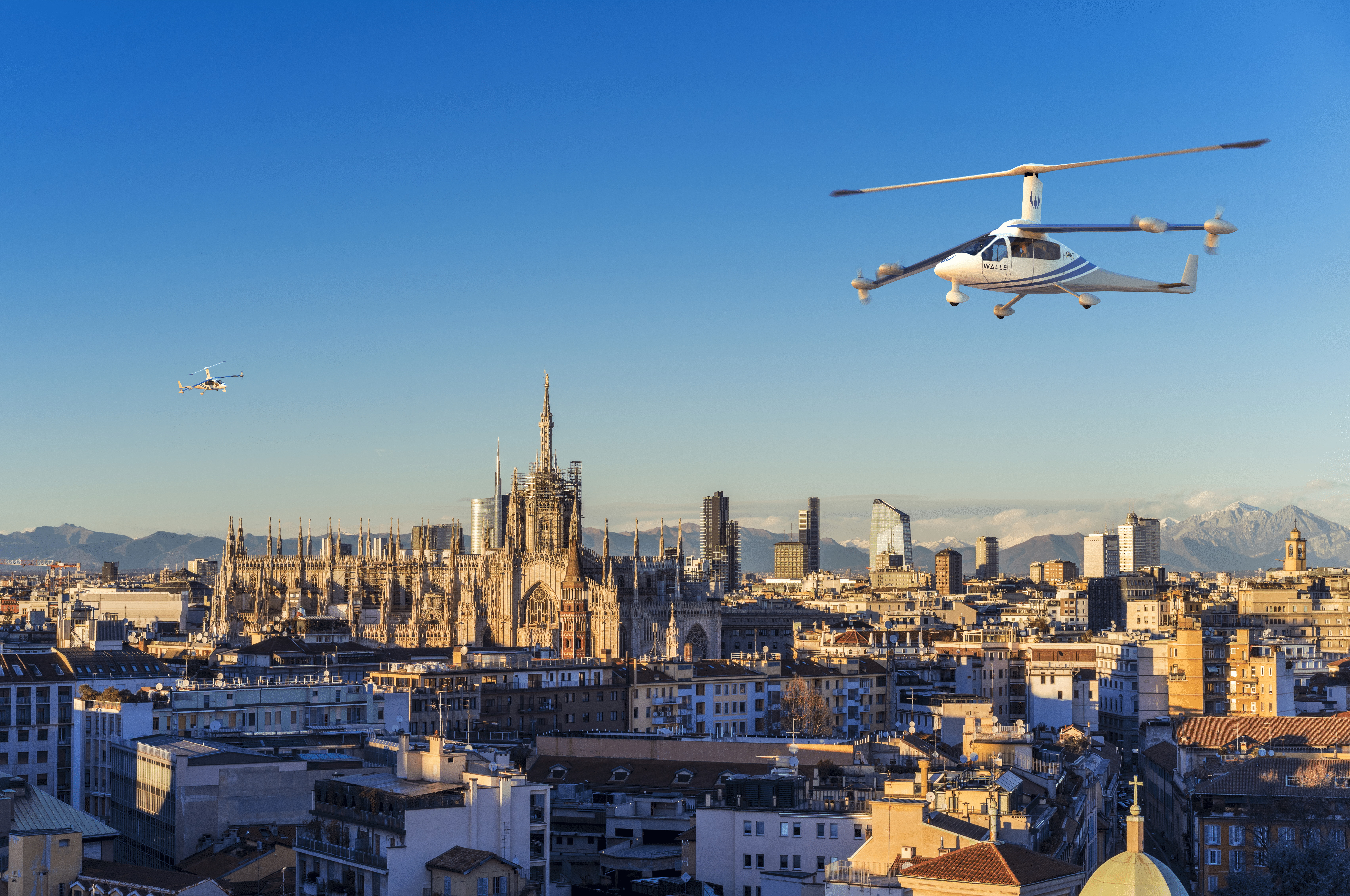

As it works to certify its Journey eVTOL aircraft under existing Part 29 rules for helicopters, Jaunt Air Mobility has had extensive outreach with the existing and new Part 135 operators it expects to be among its early customers. These include new companies such as Walle in Italy and Varon Vehicles in Colombia.

According to CEO Martin Peryea, Jaunt is putting together a playbook to support the aircraft’s entry into service, and it expects flight and maintenance manuals to be fairly similar to those for existing rotorcraft due to the common type certification basis. Working with the Vertical Flight Society and with offshore oil and gas company Shell, Jaunt has been developing the template for a safety management system, which it sees as an imperative bedrock to consistently safe operations for the new aircraft.

Jaunt’s choice of the Garmin G3000 avionics suite was also driven by its track record in service on multiple aircraft. The manufacturer is poised to announce a partnership with a leading pilot-training organization to put together a syllabus and deploy training devices.

But despite the high degree of commonality with existing aircraft, Jaunt insists that its eVTOL’s electric propulsion will deliver a safety advantage. “We will achieve performance class one from the start, and we can only do that because of the benefits from the electric motors, which deliver better response rates, and high power levels, meaning that the OEI [one-engine-inoperable performance] will exceed that of any traditional helicopter,” Peryea explained.

Peryea shares the widely held view that the early crop of AAM pilots will be drawn from established commercial aircraft operators, but he also agrees that the role will evolve to become more of what he called “a flight-deck operator.” In his view, the switch to fully autonomous flight will start in the cargo-carrying sector, with authorities requiring a cautious transition down this path.

“This class of aircraft will need to be certified and operated to the highest standards because public acceptance and trust are very important,” Peryea stated. A parallel consideration is the need to be able to secure insurance cover for operations, which in his view is by no means a given.

“This is a big concern,” he maintained. “Some in the insurance industry are saying that some of the eVTOL aircraft types are not going to get insured because of the failure modes that could occur in flight and how catastrophic these could be, particularly for the aircraft that don’t glide or autorotate [in the event of a power failure].”

Jaunt claims that the Journey’s autorotation capability and independent battery system to support flight controls mean that in the event of a failure to the main electric motors as low as 1,000 feet, the aircraft would be able to land safely within around a five-square-mile area.

Joby Aviation, which like its rival Archer is looking to raise more than $1 billion in an IPO merger, also intends to launch commercial air taxi operations under its full control in 2024. These, too, will start under existing Part 135 operating rules.

Greg Bowles, the company’s head of government affairs, said that it expects to be able to recruit a lot of existing pilots with 300 to 1,500 flight hours in their logbooks. “This is an amazing opportunity for these folks, and we will give them a dedicated Joby training course leading to a well-paying stable job,” he told FutureFlight.

“We believe it’s important to have a commercial pilot in the cockpit because it brings a high degree of knowledge, experience, and decision-making, as well as someone to manage the passengers,” Bowles said. The company is still determining whether to conduct all training in-house or use an external provider, but it will make extensive use of simulators to avoid the need for long training flights in aircraft designed to fly short distances.

Joby also has turned to Garmin for its avionics suite, which it says will support the smooth integration of the aircraft with existing airspace, using established communications, navigation, and surveillance equipment, including ADS-B In and Out capability. “This gives us the flexibility to arrive at speed [to vertiports, heliports, or runways] or come in at a perpendicular angle, which is very helpful when using busy infrastructure,” Bowles explained.

Also part of the foundation for Joby’s business model will be its own operating manual and safety management system. Since going public with its ambitious plans at the start of 2021, the company has launched a major recruitment drive to ensure that it has the expertise it needs, not only to complete certification for its four-passenger eVTOL aircraft but also to operate it.

In December 2020, Joby recruited Bonny Simi as head of air operations and people from one of its investors, JetBlue Technology Ventures. Simi has more than 17 years of experience with its parent, JetBlue Airways, having earlier served in capacities including pilot, head of airport planning, director of customer service, and vice president for talent recruitment and management.

Another key brick in Joby’s operational foundation is John Illson, its commercial aviation certification lead, who was formerly head of aviation safety with Uber and, prior to that, the head of Operational Safety Air Navigation Bureau with the International Civil Aviation Organization. In addition, he spent 26 years as an airline captain with US Airways.

The company’s advisory board also now includes former FAA Deputy and Acting Administrator Dan Elwell. He, too, has extensive experience as an airline pilot, and he also served as a senior aviation advisor to the U.S. transportation secretary.

Meanwhile, Lilium is stepping up plans to begin commercial service with its seven-seat Lilium Jet in 2024. Among the anticipated service launch locations are Florida and several undisclosed sites in Europe.

Unlike several other leading eVTOL developers, it plans to operate what it calls “regional shuttle services” over longer distances of up to around 155 miles. Longer-term plans call for the introduction of an even larger aircraft seating up to 15 passengers.

The Germany-based company started preparing for its operational phase around three years ago by hiring airline professionals and initiating partnerships with infrastructure specialists, such as airports group Ferrovial. One key partnership is with Lufthansa, which will recruit and train pilots who will then be hired by what Lilium calls its “airline partners.”

This approach marks another key distinction from many other prospective eVTOL air taxi service providers. While Lilium intends to retain full control of the digital platform through which the service will be offered and provided, it is as-yet-undisclosed operating partners who will fly the aircraft and, crucially, hold the required air operators certificate.

Working with Lufthansa Aviation Training, Lilium intends to develop its own training program based on a bespoke type rating for its aircraft. The program will use technologies such as mixed and virtual reality systems to replicate the same level of pilot preparation to support operators worldwide. Given its transatlantic ambitions, Lilium is working on approvals from both the FAA and EASA.